The Diplomatic Skills of Ambassador Terence A. Todman

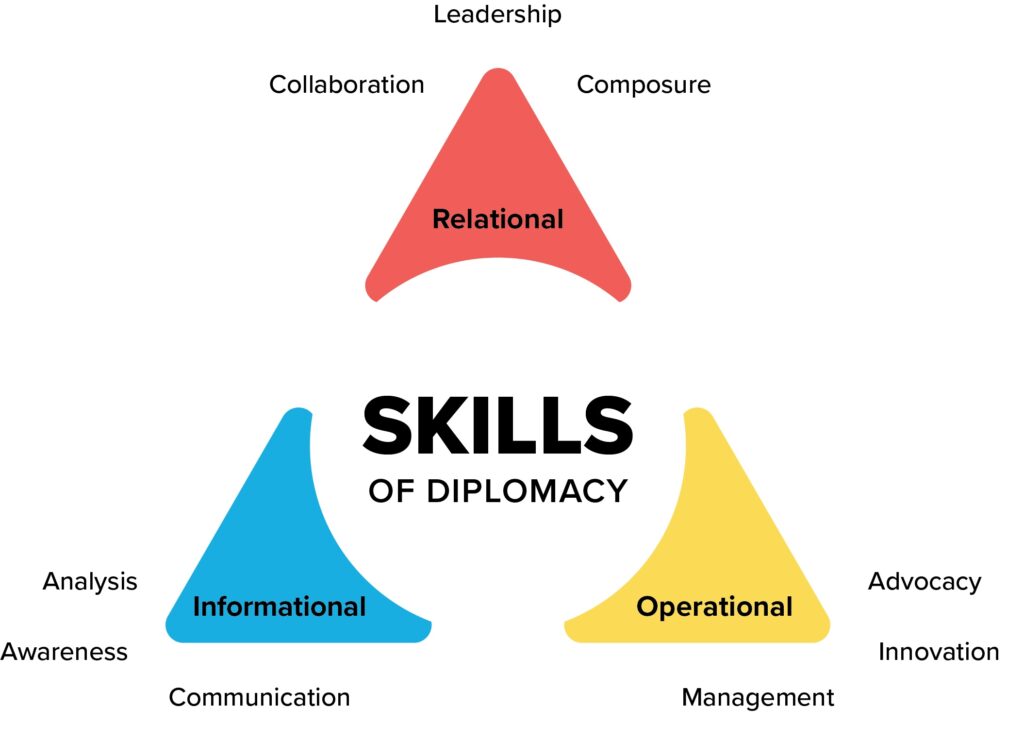

Diplomacy skills are not just any skills. They are the specific skills diplomats employ to succeed in their duties. To help the public demystify the skills of diplomacy, the National Museum of American Diplomacy categorizes these skills as informational, relational, and operational skill sets. One of the nine key diplomacy skills under operational is advocacy.

In the history of the United States, few diplomats embody the skill of advocacy more than Ambassador Terence A. Todman.

Ambassador Terence A. Todman: Advocating Civil Rights at Home and Abroad

Ambassador Terence Todman (1926–2014) was one of the first Black Americans designated a Career Ambassador, a Presidential classification for distinguished service in the U.S. Foreign Service. He was the first African American to serve as Assistant Secretary for Western Hemisphere Affairs. Todman was also an ambassador to Chad, Guinea, Costa Rica, Spain, Denmark, and Argentina.

Ambassador Todman is known for far more than his illustrious foreign service career. His fervent commitment to advocating for human rights, both in the United States and abroad, set him apart from many of his foreign service colleagues.

In a statement, Secretary of State John Kerry said Mr. Todman “was known for his outspokenness and his advocacy for equality during a time of segregation when few minorities could be found at any level in the State Department.”

“I was considered a troublemaker,” Ambassador Terence A. Todman said of his time at the State Department, “and that was all right.”

Advocating for Desegregation

In 1957, Todman started his Foreign Service Officer training at the Foreign Service Institute (FSI).

The FSI campus was located across the Potomac River from Washington in Rosslyn, Virginia. At that time, Virginia practiced racial segregation. These state laws prohibited Black people from dining in unsegregated restaurants or using the same public facilities as White people. As a result, Todman and his Black classmates could not eat lunch at FSI’s neighboring restaurant with their White colleagues.

Todman advocated for a solution. He pursued the issue within the Department until it reached the Office of the Undersecretary for Management. Initially, the Department told Todman the federal government could not interfere with state laws.

As a result of Todman’s efforts, the State Department agreed to lease half of the neighboring restaurant and erect a partition between federal employees and the general public. While the kitchen and staff served all customers, this lease created a desegregated section for Black and White colleagues to dine together.

On February 1, 2022, on the anniversary of the Greensboro sit-in, the U.S. Department of State honored Ambassador Todman’s legacy by renaming the cafeteria in the Harry S Truman building to be the Terence A. Todman Cafeteria.

Advocating for an End to the “Negro Circuit”

Todman’s first Ambassadorship was to Chad, which he said he was “out of left field” based on his diplomatic training and expertise. At that time, most Black senior diplomats were assigned to African or Caribbean posts due to their race alone. This practice became known as the “Negro Circuit.” Ambassador Todman was outspoken about this overt racial discrimination.

“What I have insisted all along, and I continue to insist, is that Foreign Service officers, whoever they are, should have the opportunity and the possibility to serve anywhere in the world.”

– Ambassador Terence Todman, 1995 interview

Todman felt trapped by a Foreign Service system that assigned Black Foreign Service Officers to only a handful of posts in Africa or the Caribbean. “The Negro Circuit,” as it came to be known, was something he resented. Todman called it “a ridiculous mold.”

A natural linguist, Todman had mastered many languages throughout his career, including Japanese, Hindi, Arabic, and Spanish. He was well-qualified to represent the United States worldwide. As many Black Foreign Service Officers held similar qualifications, he advocated not only for himself but for his fellow African American colleagues.

After serving as Ambassador to Chad and then Guinea, he threatened to quit if he were not given opportunities to serve in other parts of the world. “I resented it then, and I still do. And the United States still does that. We haven’t learned a thing over all these years,” said Todman in 1995.

In 1974, he was named Ambassador to Costa Rica, becoming the first Black American ambassador to a Latin American country.

Advocating for the People of Latin America

Todman became the State Department’s chief Latin American strategist in the Carter administration. He walked a fine line between the Carter White House’s aggressive push for human rights with the practicality of establishing workable relations with the accused countries.

When he assumed office in the spring of 1977, Brazil, Argentina, and several other Latin American countries had refused American aid because the United States criticized their human rights records. He argued that it was wrong to punish an entire country because its rulers behaved badly.

“I kept insisting that showing value for human rights, the human person, for the well-being of the individual, had to be an integral part of every single thing we did, that you shouldn’t separate human rights from other activities, as if it was something that could be dealt with by itself. But you made sure that it was incorporated into everything that you did, that it was part of a value system. That was extremely important for me. The other thing was to ensure that we did not add to the suffering of poor, suffering people as a way of getting to the despicable leaders. This was critical. Because there were many people who felt that if the leader of a certain country was not behaving properly, then the thing that you did was to punish the entire country.”

– Ambassador Terence Todman

For example, in Paraguay, people were dying of waterborne diseases. Washington policymakers worried that its leader, General Alfredo Stroessner, would take the credit if the United States provided aid. Todman persuaded U.S. policymakers that purifying the water to save Paraguayans was more important.

In February 1978, he gave a speech urging the United States to be patient with Latin America’s human rights improvements. The New York Times called the speech “a direct attack on the State Department’s human rights activists.”

Despite this backlash, President Jimmy Carter named Todman ambassador to Spain, one of the most prestigious diplomatic postings and one usually given to political appointees. He was the first Black foreign service officer to head one of the most important missions.

“I believe in pressing, screaming, cajoling, doing what is necessary to obtain the results that you establish, that you want to get. And sometimes this is done by getting up on a public platform; sometimes it’s done by going in and quietly twisting somebody’s arms. The methods vary depending on the case.”

– Ambassador Terence Todman

Sources

Terence Todman, an Envoy to 6 Nations, Is Dead at 88 – The New York Times

Being Black in a “Lily White” State Department | Association for Diplomatic Studies & Training

Library of Congress – Interview with Terence A. Todman

Michael Krenn, Black Diplomacy: African Americans and the State Department, 1945-1969 (New York and London: Routledge, 1999).

Allison Blakely, Charles Stith, Joshua C. Yesnowitz, and Linda Heywood (eds.), African Americans in U.S. Foreign Policy: From the Era of Frederick Douglass to the Age of Obama (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2015).