Commemorating 100 Years of Our Foreign Service: The 1924 Rogers Act

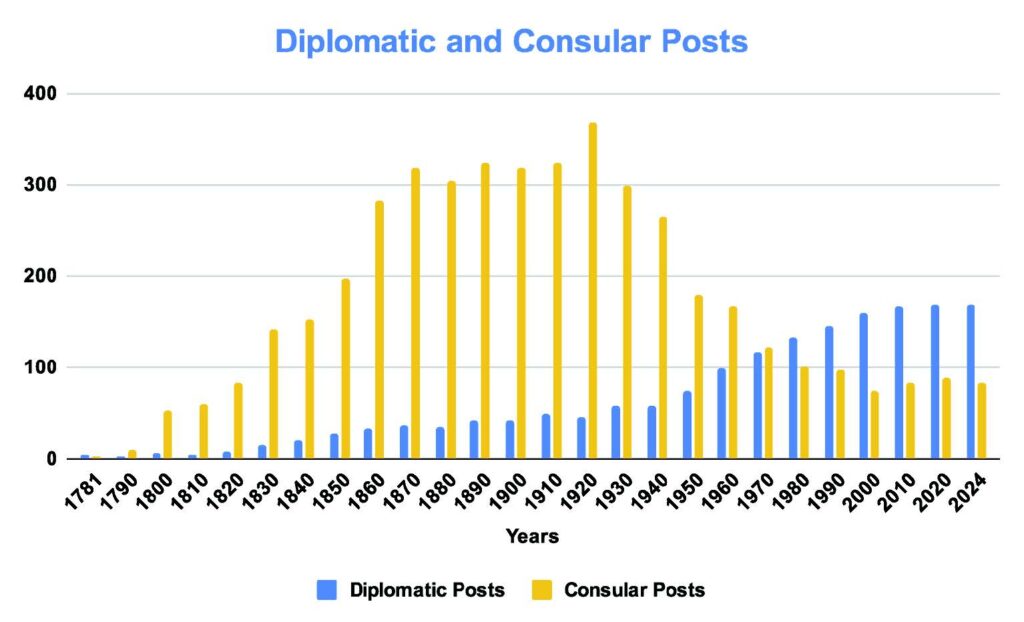

For 130 years before Congress passed the 1924 Rogers Act, American diplomats served in the system set up by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, featuring a division between the Diplomatic and the Consular Services.

The Diplomatic Service managed relations with foreign governments and its numbers were fewer than the Consular Service, which handled citizen services and commercial affairs. Low salaries, a lack of coordination between the two divisions, and politically-motivated

favoritism in hiring were the norm.

World War I and the emergence of the United States as a global power demonstrated a need for change.

Wilbur J. Carr, director of the Consular Service, pushed for reform. He found a willing partner in Congressman Rogers, a veteran who believed that a stable, professional Diplomatic Service would be essential to strive toward global peace and stability.

The Rogers Act merged the Diplomatic and Consular Services to create “The Foreign Service of the United States” establishing ranks with pay scales, merit-based hiring and promotions, and a retirement and disability system.

“…so as to permit the relative merits of candidates to be adjudged on the basis of ability alone.”

— Rep. John Jacob Rogers

Diversity in the Foreign Service

While the Rogers Act provided the legal means for a merit-based system, it would be decades before the Foreign Service reflected racial and gender diversity within its ranks.

Ambassadors Clifton Wharton Sr. and Frances E. Willis are early notable exceptions.

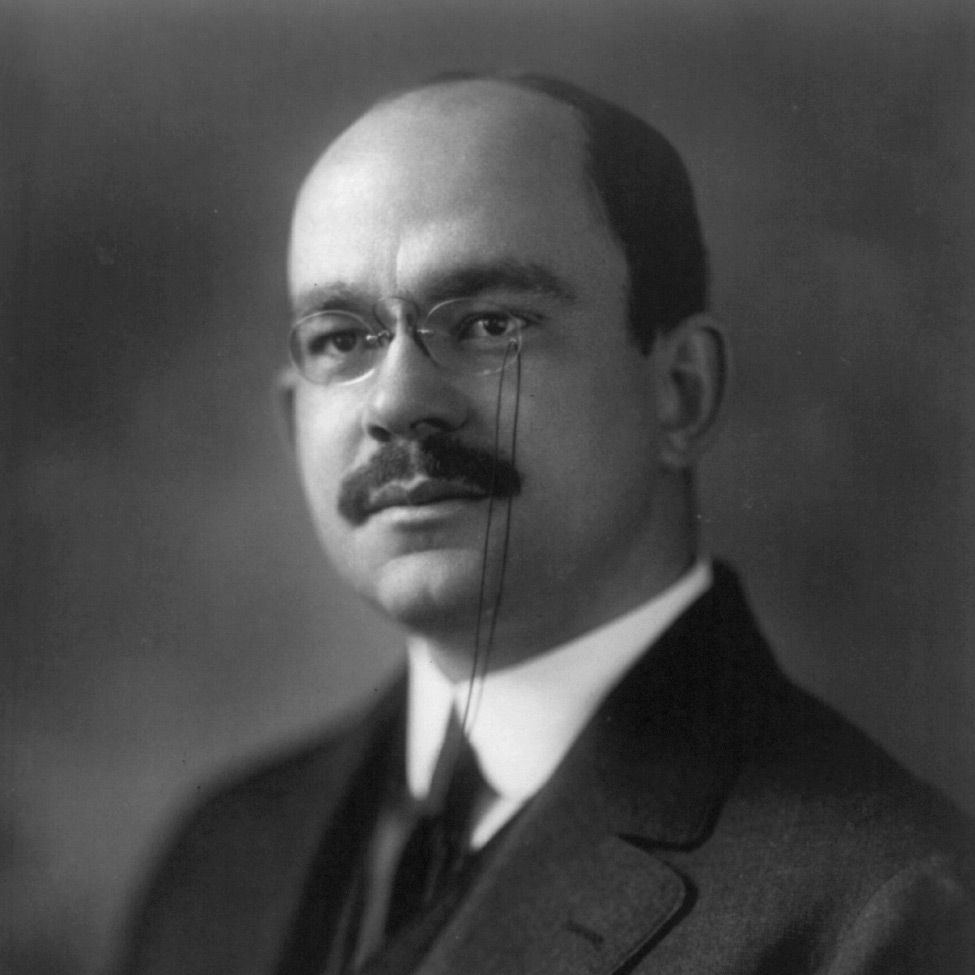

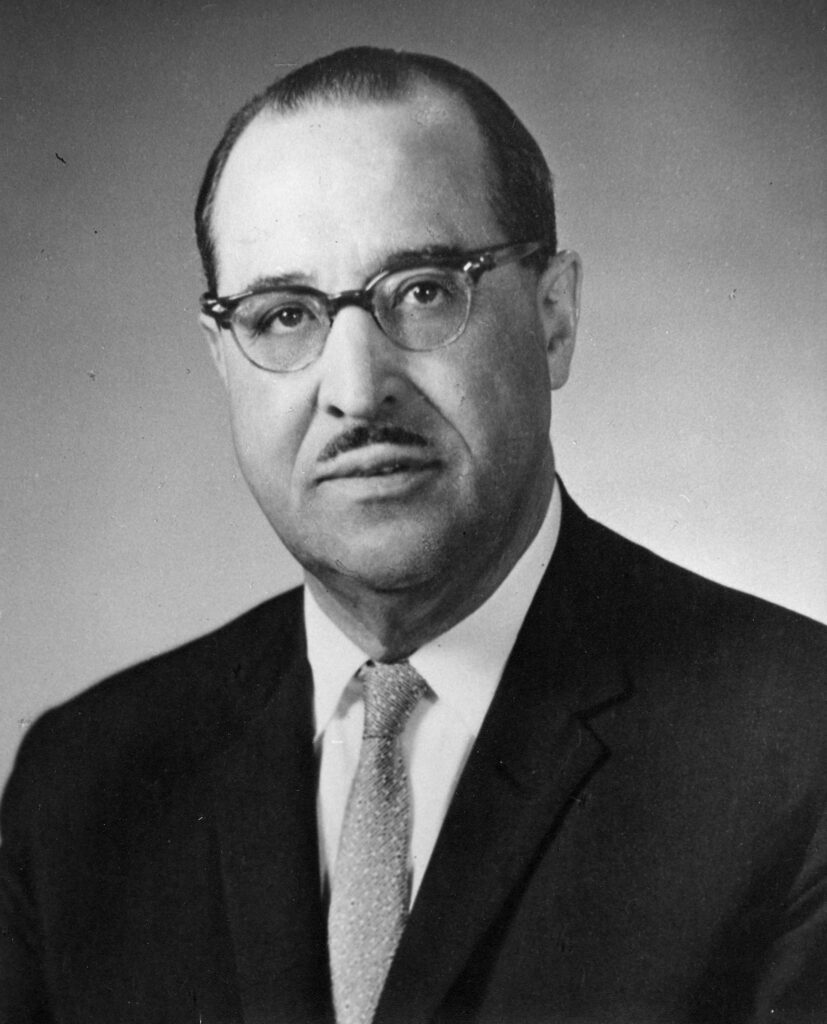

Clifton Wharton Sr.

In 1925, Clifton R. Wharton was the first African American to enter the Foreign Service after the passage of the Rogers Act.

In 1958, President Eisenhower named him minister to Romania, making him the first Black career diplomat to head a U.S. mission in Europe. Relations between the two countries were strained, as the United States demanded reparations for damages incurred during the Communist takeover. Wharton deftly negotiated a

settlement and drew the attention of Eisenhower’s successor – President John F. Kennedy. In 1961, Kennedy appointed Wharton as Ambassador to Norway, making him the first Black career Foreign Service Officer to become an ambassador.

Wharton received a law degree from Boston University in 1923 and practiced law before entering into the Foreign Service in 1925.

Initially, the State Department assigned him to posts solely in Africa and the Caribbean, which became insultingly known as the “Negro Circuit.” Ambassador Edward R. Dudley, an African American political appointee, formally protested the practice in a memorandum to the Secretary of State in 1949.

That same year, Wharton was assigned to Lisbon, Portugal, after a long battle with the personnel office; one senior official said, ”We don’t need people like him at our posts in Europe.” Despite these examples of blatant racism, Wharton would serve the rest of his distinguished career in European countries.

Frances E. Willis

Frances E. Willis entered the Foreign Service in 1927. She was the first woman to make it a career and served during many pivotal moments in international relations.

Many male colleagues praised her diplomatic skills as she rose through the ranks. In 1953, she became the first female Foreign Service Officer to serve as

Ambassador to Switzerland, a country that did not permit women to vote. She also served as Ambassador to Norway before rising to the rank of career ambassador in 1962, the highest rank in the Foreign Service, while Ambassador to Ceylon (Sri Lanka).

A Ph.D. graduate from Stanford and professor of political science before joining the Foreign Service, Willis served for 37 years. Noting she had “a hump of prejudice to work against,” with senior male diplomats, she was serving in Belgium in 1940 when the Nazis invaded.

Briefly in charge of the U.S. embassy, she forced an apology from a Nazi general for damage done to United States property inside Brussels’ French embassy.

During her ambassadorship to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in 1962, Willis cautioned the Ceylonese government that the United States would suspend aid if it did not compensate for the seizure of U.S.-owned oil businesses. A TIME magazine article about the issue quoted her saying she believed, “the basis for diplomacy is to be tactful and sincere at the same time.” The United States suspended aid to Ceylon eight months later.

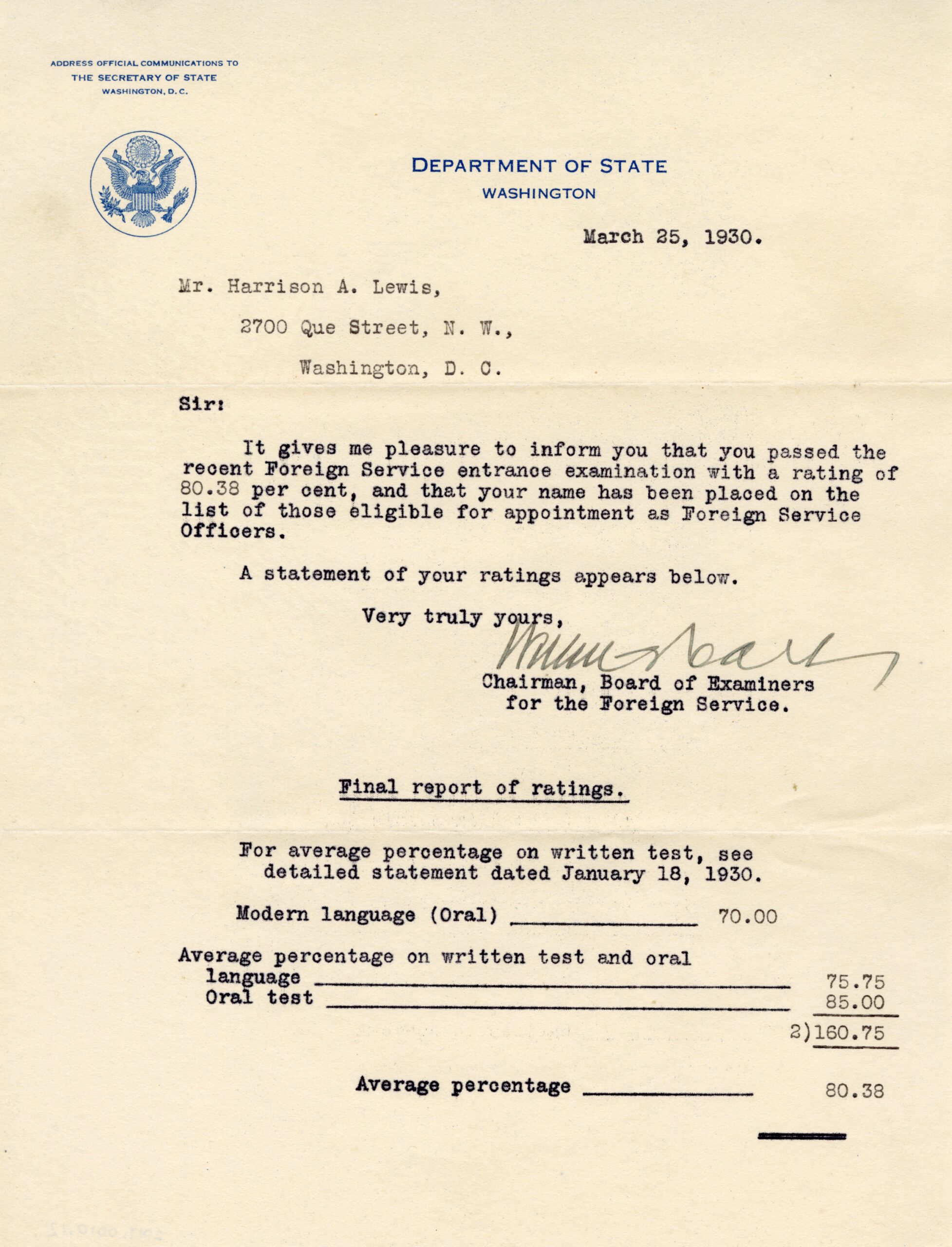

The Foreign Service Test

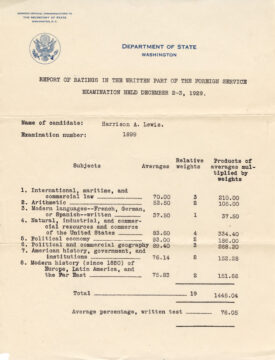

Under the Rogers Act, a two-part examination was the key hurdle for any candidate wishing to join the Foreign Service. The letter below to Harrison A. Lewis, who took the written part of the exam in December 1929, broke down his score: 76.05%.

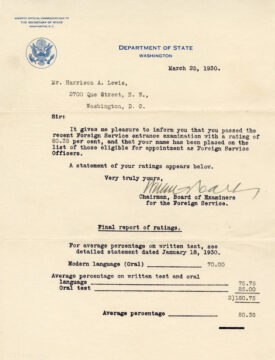

The second part of the two-part examination was an oral test. Harrison A. Lewis received this result about three months after the results for the written test. He scored slightly better on this test than the written, with an average of 80.35%

Training for the Foreign Service

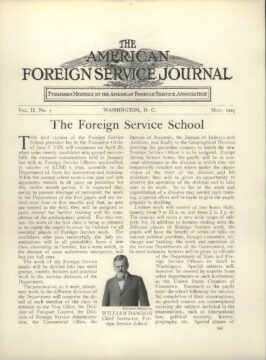

In June 1924, shortly after the Rogers Act became law, an executive order by President Calvin Coolidge established a training school for new Foreign Service Officers. The first page of the May 1925 American Foreign Service Journal announced and described the school, whose first session began on April 20 with “some twenty candidates who passed successfully the entrance examinations.”

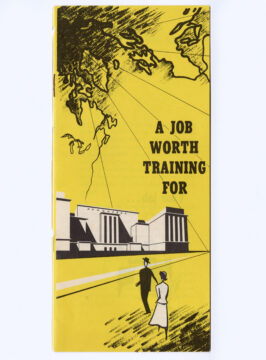

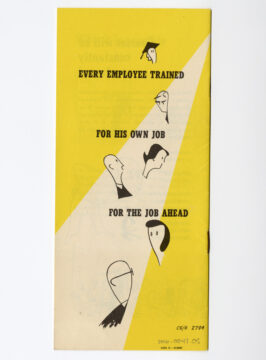

The period immediately following World War II saw a surge in the growth of the Foreign Service and overseas posts. The pamphlet below provides an overview of the variety of training available at the Foreign Service Institute—for both Foreign and Civil Service employees—and imparts to employees the importance of their participation in training.

Language Training in the Foreign Service

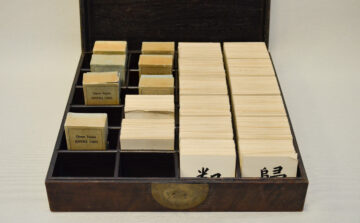

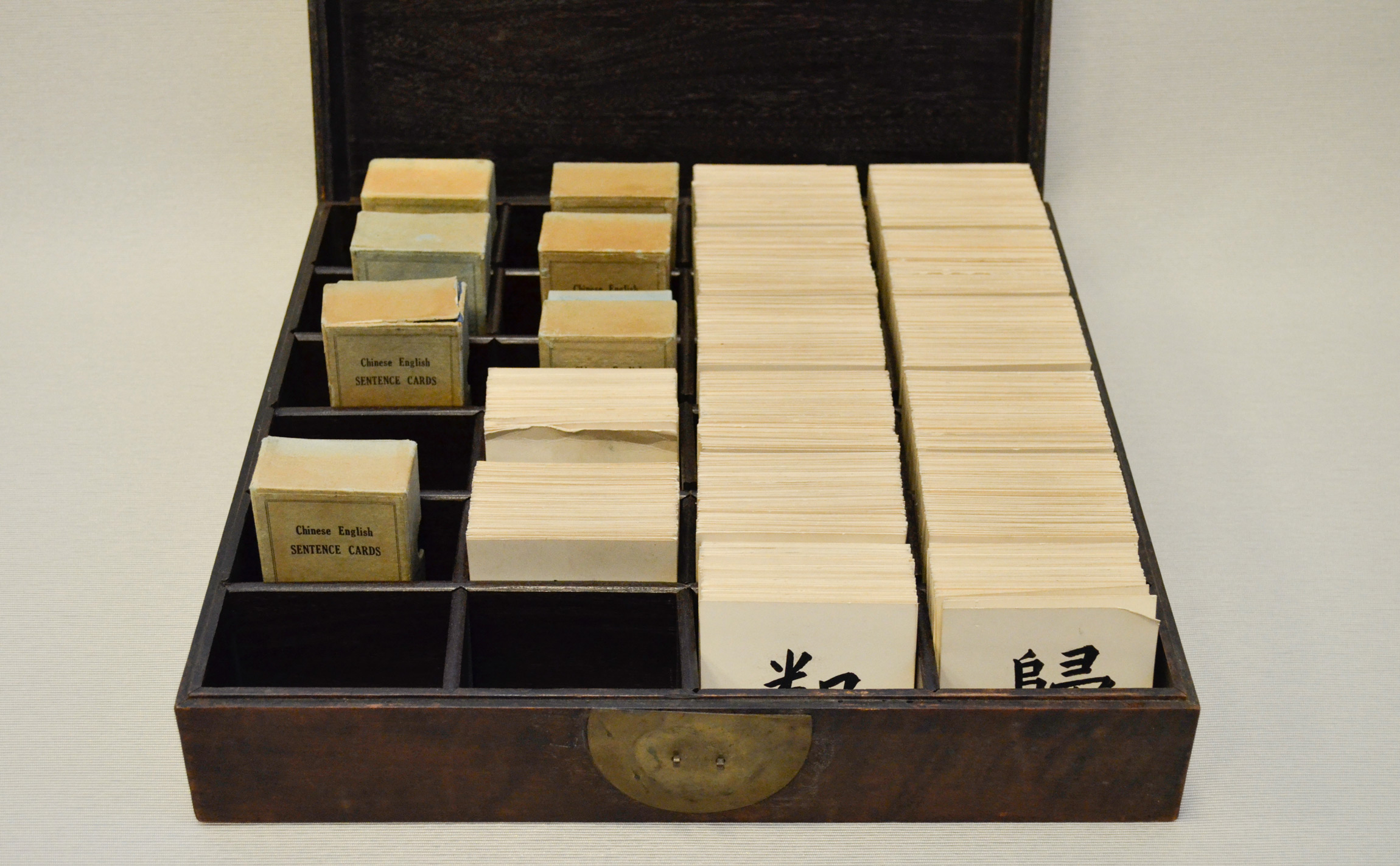

These Chinese-English flashcards are from a set of over 2,000 handmade cards stored in a custom box, pictured here. They were used by a Foreign Service Officer assigned to Peking (Beijing) in 1934 to acquire language skills vital for his diplomatic duties.

All U.S. Foreign Service Chinese Language Officers were trained in Peking from 1902 until 1949, when U.S. diplomatic and consular representation on China’s mainland ceased.

Sealing the Deal

The Rogers Act merged the Diplomatic Service and Consular Service into one Foreign Service. This seal, which was used with melted wax, reads “American Consular Service” and “Oslo, Norway” around the Great Seal.

The use of wax seals as part of consular work—once routine—has become increasingly rare over the decades. State Department guidance from 1999 defined these seals and their purposes: “a small metal engraving seal die affixed to a short wooden handle, used for making impressions on wax. It is used to seal premises and effects in estate cases, to seal envelopes and packages, or other items as needed.”

Watch to Learn More about the U.S. Foreign Service

About the Spotlight

Throughout the year, the National Museum of American Diplomacy (NMAD) highlights different stories and artifacts of diplomacy through our rotating exhibit: Spotlight on Diplomacy.

This exhibit is temporarily on display at the 21st Street NW entrance of the Harry S Truman Building. To allow more of the public to view these stories during the pandemic, this exhibit is also available here on our website for virtual viewing.