Lesson Plan

History Through the Lens of Diplomacy: From Saigon to Hanoi

This lesson engages students in a critical analysis of U.S.-Vietnam relations, exploring changes over time as well as diplomacy’s key role in post-conflict reconciliation.

2025 marks 30 years of reestablishing diplomatic relations between the United States and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Diplomacy was central to the “normalization” process and included sensitive talks about war legacies, shared economic and security issues, and addressing human rights.

April 1991

The U.S. presents a mutually beneficial plan to Vietnam for a phased normalization of diplomatic relations. Vietnam accepts the conditions. USAID assistance is permitted to address pressing humanitarian concerns.

December 1991

U.S. lifts its travel ban to Vietnam and resumes State Department-facilitated exchange programs.

February 1992

The U.S. and Vietnam establish the Joint Task Force-Full Accounting to achieve the best possible accounting of Americans missing in action.

July 1993

The U.S. agrees that Vietnam should participate in international lending through the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

February 1994

The U.S. lifts its trade embargo on Vietnam.

May 1994

The U.S. and Vietnam sign a consular agreement.

May 1995

Vietnam provides the most detailed and informative documents to date related to missing Americans, positively affecting U.S. popular opinion.

June 1995

Veterans of Foreign Wars of the U.S. announces support for the normalization of relations with Vietnam.

August 1995

The U.S. officially opens the U.S. Embassy in Hanoi, Vietnam’s capital, and Vietnam opens its embassy in Washington, D.C.

The 1973 Paris Peace Accords aimed to end the Vietnam War. Under the agreement, the U.S. withdrew its troops, maintaining its diplomatic presence despite doubts that South Vietnam could defend itself alone. Fighting resumed in 1974.

By April 1975, Viet Cong forces advanced south. The U.S. began evacuating Americans, South Vietnamese military allies, and those who worked for the U.S. government from Tan Son Nhut airbase. Foreign Service Officers like Kenneth Moorefield were pressed into consular duties to decide who would receive exit visas. The officers faced an emotional and professional dilemma as they were under strict orders to limit visas to individuals and their immediate families. He and others saved many by processing people they knew had illegal paperwork.

Helicopter evacuations began at the U.S. embassy on April 29 after the Viet Cong bombed the airbase. Thousands of Vietnamese thronged the embassy wall, making quick identification of those who worked for the U.S. impossible. John Bennett, Deputy Director of USAID, instructed his staff to tear off the front page of the embassy phone book and wave it as proof of their employment. It worked, and embassy security pulled them over the wall.

Moorefield was the last U.S. embassy staffer to evacuate from the embassy roof in the early morning of April 30. He could see hundreds of Vietnamese sitting in the compound waiting for help that would never come.

On April 29, 100 miles south of Saigon, the U.S. Embassy evacuation coordinator gave orders to Francis “Terry” McNamara, the U.S. Consul General in Cần Thơ, to evacuate only U.S. citizens by helicopter. McNamara refused to abandon the Vietnamese who worked for the U.S. government and asked his superiors for permission to evacuate by boat to accommodate his staff and their families. Denied. They argued, and McNamara got his way.

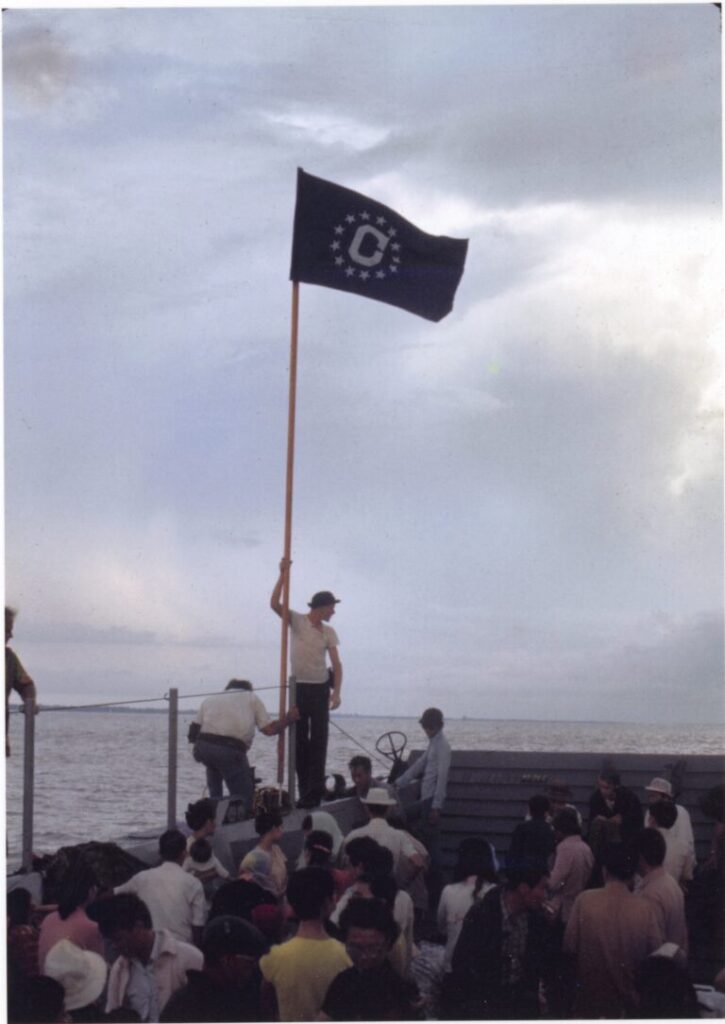

The only other way out of Cần Thơ was the Mekong River. The safety of U.S. Navy ships lay 70 miles south in the South China Sea. McNamara found two lightly armored barges and set off with 300 Vietnamese and 18 Americans aboard.

Flying a U.S. consular flag, McNamara personally piloted one of the boats. The Viet Cong launched rockets from the shore, and consulate Marines returned fire. Fortunately, no one aboard was injured, and after a harrowing narrow pass where they barely escaped an ambush, they made it to safety.

McNamara saved all the evacuees by challenging orders for what he considered to be his “clear moral responsibility to those who had given their loyal service.”

This oral history captures Anne Pham’s family’s harrowing escape and her search to honor the unsung heroes who made it possible.

Step inside our vault to uncover the hidden networks of Vietnam’s leaders and the preservation challenges of a historic U.S. consular flag.

Throughout the year, the National Museum of American Diplomacy (NMAD) highlights different stories and artifacts of diplomacy through our rotating exhibit: Spotlight on Diplomacy.

This exhibit is temporarily on display at the 21st Street NW entrance of the Harry S Truman Building. To allow more of the public to view these stories while we’re under construction, this exhibit is also available here on our website for virtual viewing.