Passport Travels: Meyer Franklin Kline, globetrotting guidebook editor

Have a case of wanderlust? As you take a look at this passport from the museum’s collection, join Meyer Franklin Kline and his wife Mildred Kline as they traveled the world in 1915 and 1916.

The Klines, originally from California, planned to travel to Russia, China, Japan, India, the Straits Settlements, and Great Britain, “representing [a] Japanese steamship company.” This U.S. passport — like others from the same time period — included an area to list where the traveler was planning to travel and the reason why.

A dream job

Meyer Franklin Kline, who went by Franklin, dreamed of traveling the world from a young age. In 1900, at the age of 18, he rode a bicycle from his home in Los Angeles all the way to Montreal in Canada. From there, he boarded a ship bound for Europe and attended the World’s Fair in Paris.

“How fine it would be if I could get up some sort of a guidebook so I could get expenses paid for a trip around the world,” Franklin recalled thinking during his early years in an interview with the Los Angeles Times in 1935. And that is exactly what he did.

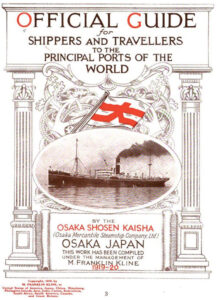

Beginning around 1913, Franklin spent over twenty years traveling the world while working for the Osaka Mercantile Steamship Company Ltd. in Japan as the manager and editor of their annual reference book, Official Guide for Shippers & Travellers to the Principal Ports of the World. Made available in passenger cabins on the company’s ships, it served as both a handy reference book for global travelers and a promotional piece for the company’s services and history. Its hundreds of pages were chock full of facts, figures, and photos about ships and their routes — as well as about countries and major cities across the globe.

A well-traveled passport

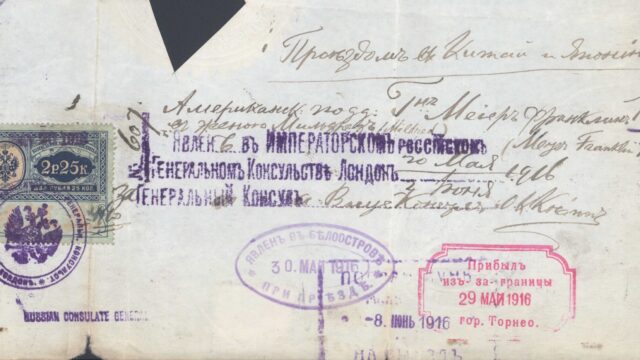

This single-page passport, issued in June 1915, was one of many Franklin used during his travels over the years. The numerous stamps it bears — not to mention the worn edges and tears — speak to the travels Franklin and Mildred undertook in 1915 and 1916.

A series of stamps across the front and back show one particularly long trip in June 1916, stretching from London to Japan. Starting out in London, they made stops to the U.S. Consulate General to have their passport’s expiration date extended on May 23 and June 2 — paying a total of $2 in fees in the process. They also visited the Russian Consulate General on June 2 to obtain a visa, thereby gaining approval to travel through Russia to China and then Japan.

Taking a northerly route from London through the Nordic countries — thereby avoiding Central Europe and the active battlefields of World War I — they traveled to Newcastle-upon-Tyne, where they would have boarded a ship headed north. Stamps show them stopping in Haparanda, Sweden, on June 11th and then crossing the border to Tornio, Finland, the same day. From Tornio, they traveled on to Beloostrov, Russia, on the outskirts of St. Petersburg, arriving on June 12. Their long journey across Russia en route to China was most likely made by train.

The back side of the passport features several lines in traditional Chinese. This is largely a replication of the standard “greeting” language from the front of the passport, included for the convenience of Chinese officials the traveler might encounter on their journey. “Smooth passage shall be granted to the aforementioned passport holders,” it requests for Franklin and Mildred. “No officer shall block their passage or pose any other obstacles to their visits; instead, protection and assistance shall be provided wherever necessary.” It also duplicates areas seen on the front for descriptive information about the bearer (age, height, shape of nose, mouth etc.)

Though no stamps mark the dates of their journey through China, there is a stamp from a government official in the Chinese city of Dalian and an accompanying chop (or official seal) — indicating that Franklin and Mildred passed through on their journey. Dalian is a port city on the Yellow Sea and would have been a likely point of departure for a ship sailing for Japan, the final destination of their trip.

Several other trips are evident from the stamps and visas spread across this passport. One stamp by a Colonial Secretary in Hong Kong and a handwritten notation beside it — simply “Travelling to Australia” — shows Franklin and Mildred embarking on another long journey in November 1916.

Reflecting on a life of travel

By the time he was interviewed for the 1935 Los Angeles Times article, Franklin had made at least 22 trips around the world. He sometimes even circled the globe twice per year: once in the northern hemisphere, once in the southern. Over the course of the previous year, he estimated he had traveled more than 55,000 miles.

During his trips, he particularly enjoyed collecting rare Chinese objets d’ art (art objects). Since he frequently spent 11 months of the year traveling, he sent them to his home in Washington, D.C., for safekeeping.

Reflecting on his life of travel, Franklin revealed his priorities and his unabated wanderlust. “I have made money, yes, but that was the secondary consideration. I am just as much of a kid in my wish to see the world as I ever was. One can never finish seeing the world, you know.”