On December 19, 2019, several patients from Wuhan, China showed pneumonia-like symptoms that did not respond well to typical treatments. By the end of January 2020, a new virus called SARS-CoV-2 had infected people in Taiwan, Japan, Thailand, and the United States. In March 2020, fewer than 100 days after its discovery, the virus had infected people on every continent.

The virus and the illness it causes, COVID-19, would kill seven million people, cost the United States $14 trillion dollars, push over 70 million people into extreme poverty, and worsen inequality within and across countries.

As the COVID-19 pandemic illustrates, preventing the spread of diseases internationally is critical to our national health, commerce, trade, and security.

The urgent need to quickly respond to global health crises inspired the creation of the U.S. Department of State’s new Bureau of Global Health Security and Diplomacy in 2023. The Bureau combined the Office of International Health and Biodefense within the Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs, the Coordinator for Global COVID-19 Response and Health Security, and the Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator.

While the Bureau is new, global health diplomacy is not. Since the late 19th century, the United States has cooperated with other nations to address the spread of infectious diseases, such as cholera and yellow fever.

Today,

Today, the Bureau of Global Health Security and Diplomacy works with government and non-governmental partners to stop diseases from spreading, develop policies, and strengthen health infrastructures. This work has detected infectious disease threats early, prevented avoidable outbreaks, mitigated the spread of diseases, and responded to crises.

COVID-19 is a very different disease from HIV/AIDS, for example. Yet, the global cooperation required to address these diseases can look similar.

“A pandemic is not only a health crisis. It’s a security crisis; it’s an economic crisis; it’s a humanitarian crisis.”

– Secretary Antony Blinken at the launch of the Bureau for Global Health Security and Diplomacy, August 1, 2023

Case Study:

President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) was first identified in 1984 by French and American scientists. While HIV is a viral infection, Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) is the most advanced stage of the disease caused by the virus. By 1994, AIDS was the number one killer of young adults in the United States. However, the increased availability of treatment reduced the U.S. mortality rate by the end of the decade.

The same was not the case in regions including Sub-Saharan Africa and the Caribbean. More than two-thirds of the world’s cases of HIV/AIDS were in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2003, but few were receiving the lifesaving medications that extended the lives of Americans.

Infant mortality had doubled, child mortality had tripled, and life expectancy had decreased by 20 years in the region. For this reason, President George W. Bush announced the creation of the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) during his State of the Union address in January 2003. At the State of the Union, President Bush said: “In the face of preventable death and suffering, we have a moral duty to act, and we are acting.”

The State Department’s Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator and Global Health Diplomacy leads, manages, and oversees PEPFAR. Through a large network of partners, international governments, local partners, faith-based organizations, and civil society non-profits such as the Elton John AIDS Foundation, PEPFAR has saved over 25 million lives since 2003 and enabled more than 5.5 million babies to be born HIV free. In 2022, PEPFAR supported 20.1 million people on life-saving antiretroviral treatment.

Additionally, more than 20 PEPFAR-supported countries have met epidemic control of HIV according to the UN AIDS Program (90% of the population knows their HIV status, 90% of those who are HIV+ are receiving antiretroviral treatment, and 90% of those receiving treatment can no longer transmit HIV). Further, the creation of healthcare infrastructure to test for HIV and deliver treatment has been vital for combating Ebola, avian flu, and COVID-19.

The PEPFAR program has been widely successful, showing that the U.S.’s investment in global health can save and enrich millions of lives internationally. PEPFAR embodies the very best of American innovation, scientific excellence, and capacity to work in partnership with other nations in the service of shared goals of well-being.

From the Collection

Pratt Pouch (Duke University Pratt School of Engineering Developing World Healthcare Technologies (DHT) Lab)

One of PEPFAR’s focus areas is the prevention of maternal-to-child transmission of HIV. The risk is especially great if the woman becomes HIV-positive when she is pregnant or breastfeeding. If the mother is receiving antiretroviral treatment and the baby receives antiretroviral treatment for four to six weeks after birth, the risk is reduced to less than 1%.

Treatment must be started within three days of giving birth to the baby for the greatest reduction in risk. The most common way to deliver antiretrovirals for babies was through a syringe, but the medicine does not last long. However, many mothers give birth at home due to a lack of hospitals, which may prevent them from giving their babies the medicine in the necessary time frame.

Pratt labs at Duke University created these ketchup-packet-sized pouches, which extend the expiration of the antiretrovirals for 12 months. Pharmacists fill the pouch with the amount needed for the baby, and the filled pouches can be given to mothers at clinic visits when they are pregnant. This way, mothers who give birth at home may administer the medicine in the time frame without having to worry about the antiretrovirals expiring.

Because of PEPFAR initiatives like the Pratt pouch and others, over 5.5 million babies are HIV-free and new HIV infections for children have been cut in half. PEPFAR hopes to accelerate this progress through the creation of the Safe Births, Healthy Babies Initiative: a two year $40 million effort beginning in 2024.

This pouch was donated in 2015 to the museum by USAID’s U.S. Global Development Lab. The pouch was part of the “Saving Lives at Birth: A Grad Challenge for Development” programs in Ecuador and Zambia.

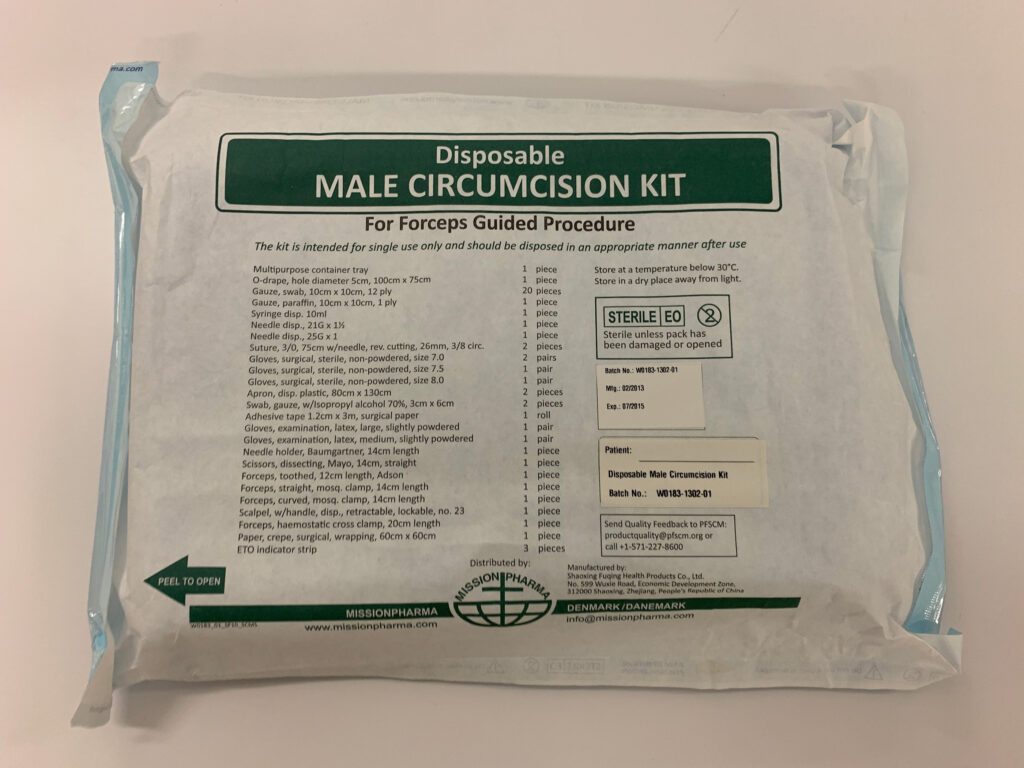

USAID Disposable Male Circumcision Kit

Male circumcision reduced the chance of female-to-male sexual transmission of HIV by 60%. While not as effective as the routine use of condoms, circumcision can have a profound impact on the spread of HIV.

Since 2007, the WHO and the UN AIDS Program have recommended circumcision as a key component of combination HIV prevention in 14 countries in Eastern and Southern Africa with a high HIV prevalence and low levels of male circumcision. Voluntary circumcision may also serve as an entry point to other health services, such as testing for HIV and receiving vaccines.

Health Diplomacy in Photos

The importance of identifying, treating, and if possible, eradicating infectious diseases has long been recognized as important for the safety and security of American citizens. As General, George Washington even required members of the Continental Army to be vaccinated against smallpox. In writing to physician William Shippen, Jr., Washington writes that he “has more dread from it [smallpox infecting the Army] than from the Sword of the Enemy.”

The program to eliminate smallpox from the world began in 1958 when the U.S. Department of State asked the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to aid in stopping a smallpox outbreak in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).

COVID-19 vaccine distribution, COVAX

The United States has donated over 688 million COVID-19 vaccines in partnership with COVAX, the World Health Organization’s COVID-19 vaccine delivery partnership, to 117 countries around the world.

Polio vaccines

Ensuring children receive routine vaccines is important for ensuring global health and safety.

Ebola infection control

Outbreak containment and health education on infection control are vital to prevent disease from spreading across borders. USAID provided resources and education to ensure infection control during the Ebola outbreak in Western African nations in 2014-2016.