Introducing the Historical Diplomacy Simulation Program

How can we learn diplomacy through history?

In June 2021, the National Museum of American Diplomacy (NMAD) launched the Historical Diplomacy Simulation Program. This program provides educators with the opportunity to bring diplomacy and the work of U.S. diplomats into the classroom. Historical diplomacy simulations also offer teachers a way to internationalize their curriculum.

These historical diplomacy simulations are part of NMAD’s larger catalog of diplomacy simulations, most of which occur within hypothetical scenarios.

About Diplomacy Simulations

In most classrooms, discussions about the work of U.S. diplomats and how the U.S. government engages in global issues are absent from the curriculum. To fill this gap, NMAD has developed educational programming to help students better understand diplomacy. These resources show students that many of the opportunities and challenges before the United States are global in source, scope, and solution.

Our signature educational resources are our diplomacy simulations. NMAD’s diplomacy simulations teach students about the work of the U.S. Department of State and the skills and practice of diplomacy as both a concept and a practical set of 21st-century skills. Stepping into the role of diplomats and working in teams, students build rapport with others, present clear arguments, negotiate, find common ground, and compromise to find a potential solution to a real-life historical crisis.

Introducing Three New Historical Diplomacy Simulations

The goal of NMAD’s Historical Diplomacy Simulation Program is to engage participants in the art and practice of diplomacy while introducing them to the contributions of the State Department and U.S. diplomats in the context of a historical event addressed in the teaching of U.S. history.

The Historical Diplomacy Simulation is a project with the Una Chapman Cox Foundation’s initiative on American Diplomacy and the Foreign Service. The program was developed along with partners National History Day and George Mason University’s Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, the Historical Diplomacy Simulation Program offers three simulations:

- The Barbary Pirates Hostage Crisis: Negotiating Tribute and Trade

- The Spanish and American Conflict of 1898: Treaties and Self-Determination

- The Suez Canal Crisis: National Sovereignty versus International Access to Waterways

Here are summaries of the scenarios in these three historical diplomacy simulations:

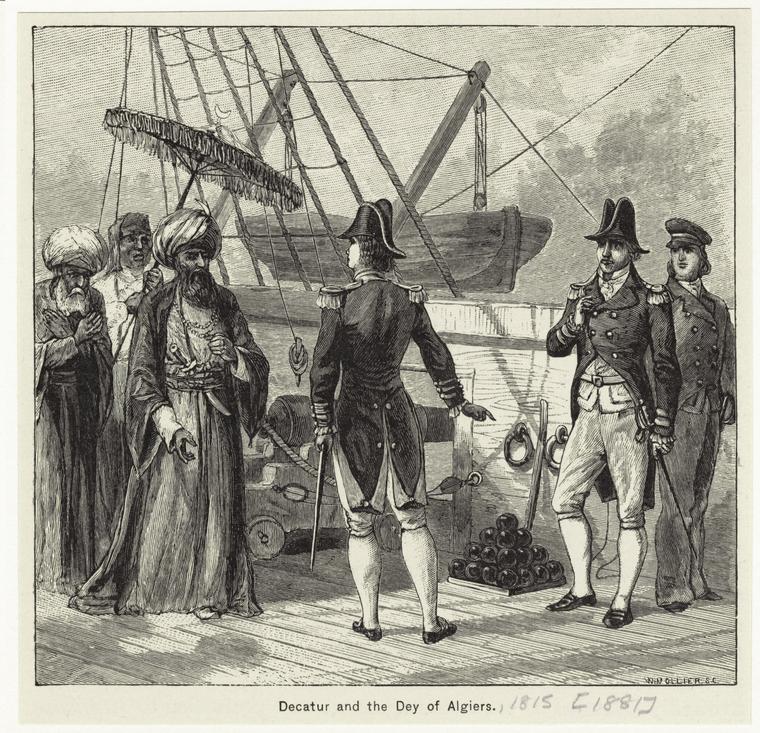

The Barbary Pirates Hostage Crisis: Negotiating Tribute and Trade

For almost 300 years, leaders of the North African Barbary States hired ship captains to capture foreign ships in the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. These captains, known as corsairs, kept the ships and cargo, then ransomed the crew or forced them to work in captivity.

This practice was a way for these semi-independent states of the Ottoman Empire to generate money. Some wealthy countries, such as Great Britain, would sign treaties with or make payments to the Barbary States, permitting their merchants to travel the seas freely. These cash payments and preferential trade agreements were called tributes.

When the United States gained its independence in 1783, it lost the protection of the British navy, and Barbary corsairs captured two American ships in 1785. As a new nation with limited revenue to support its government, the United States had limited funds to pay tribute and many Americans opposed it on principle. In 1793, Algerine corsairs captured 11 more American ships and 100 citizens, prompting a commercial and humanitarian crisis that could not be ignored.

With no navy or substantial annual revenue, how could the United States pay hefty ransom fees and prevent this from happening again? Would the Barbary States even agree to negotiate terms when they clearly had the upper hand?

The Spanish and American Conflict of 1898: Treaties and Self-Determination

By the 1830s, independence movements reduced Spain’s colonies to Cuba and Puerto Rico in the Caribbean, the Philippines, and several smaller islands in the western Pacific Ocean, including Guam, the Marianas, and the Marshall Islands.

At the same time, the United States was increasing its global diplomatic presence and economic power, warning European countries throughout the 19th century from attempting to recolonize countries in the Western Hemisphere.

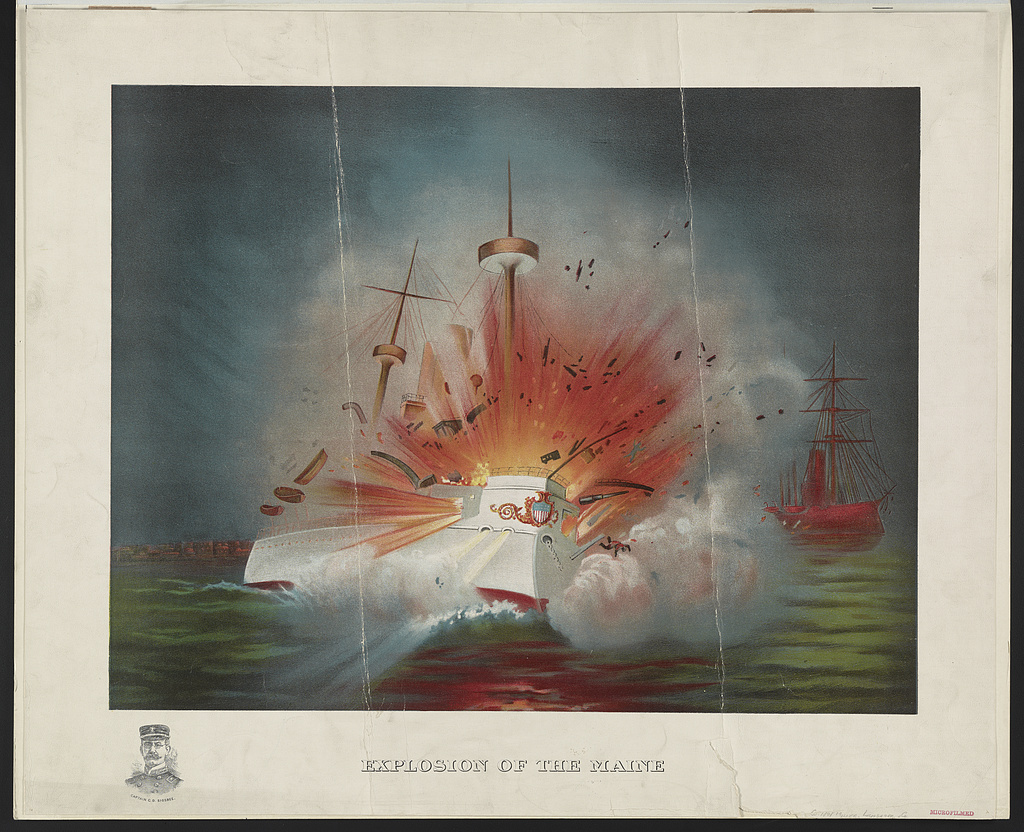

Meanwhile, the American public read newspaper reports of severe Spanish treatment of revolutionaries in Cuba and the Philippines. Many in the United States wanted to go to war against Spain because of these atrocities, and others wanted to use it as an excuse to expand America’s territory. Some wanted to help Cuba become a free and independent country while some wanted the United States to replace Spain and take control over Cuba, as well as the Philippines, to increase its global military and economic power. All could agree that America’s commercial investments in the regions must be protected.

The United States sent the USS Maine battleship to Havana Harbor to protect its citizens and interests in the Spanish-Cuban conflict. On the night of February 15, 1898, an explosion rocked the ship, which eventually sank, killing 266 sailors. While unclear if this was an attack or accident, the press in the United States blamed Spain immediately, and war between the United States and Spain seemed inevitable.

Could the Spanish keep a stronghold on their last colonies, or will the Cuban and Filipino people gain independence? And would the United States press be able to influence the United States to wage or avoid war?

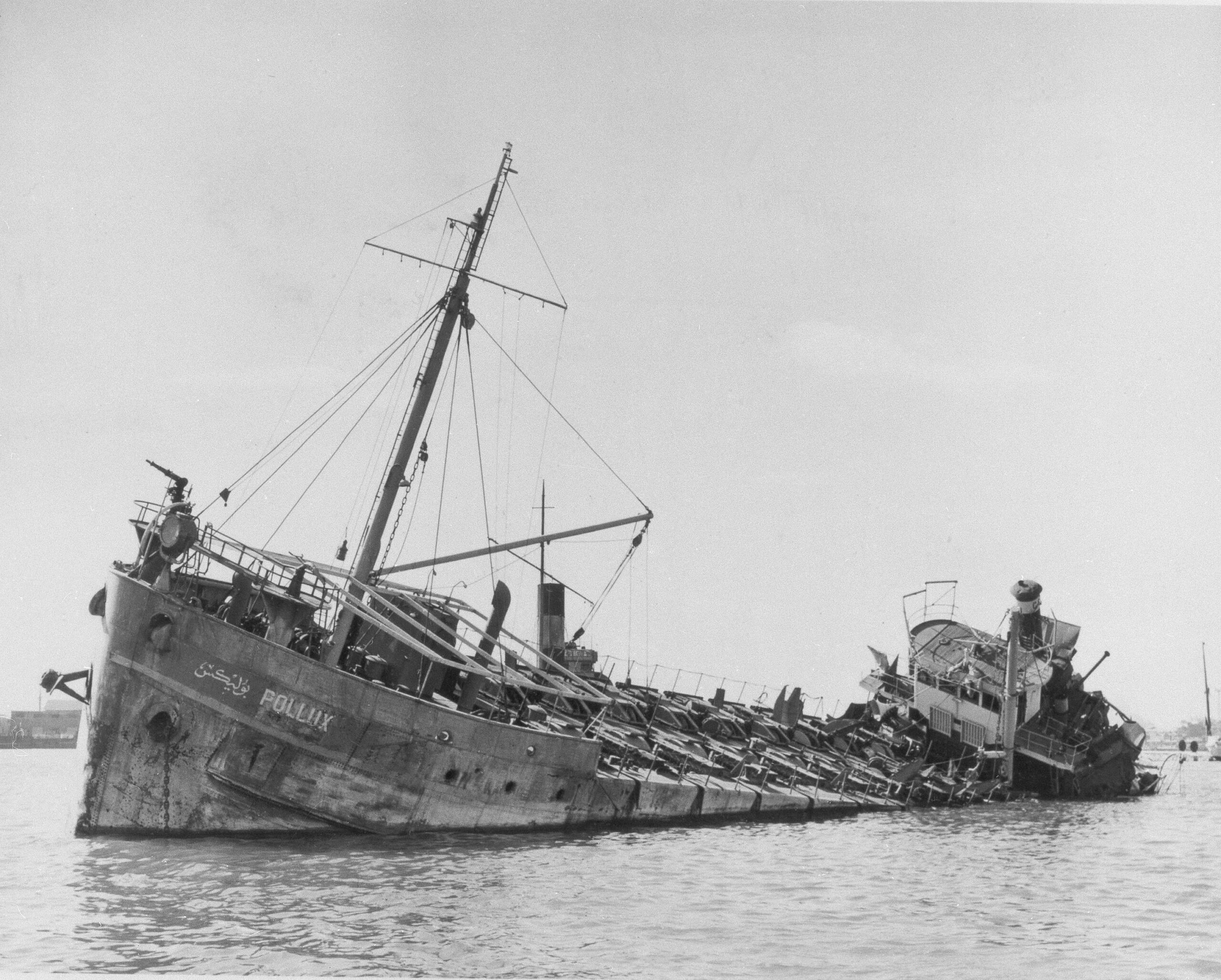

The Suez Canal Crisis: National Sovereignty versus International Access to Waterways

The Suez Canal was completed in 1869 to connect the Mediterranean and Red Seas, creating an essential waterway for global trade, as ships no longer had to navigate around the Horn of Africa.

At the time it opened, the canal was 164 kilometers, or roughly 100 miles, long. Without the canal, the circumnavigation around Africa is 9,654 kilometers or 6,000 miles. For most of its existence, the canal was managed by the Suez Canal Company, which was owned by Great Britain and France.

On July 26, 1956, Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nassar nationalized the canal, intending to take control of the canal’s operation and its revenue.

The world was still recovering from World War II with new national border conflicts and the onset of the Cold War. Many nations depended on the Suez Canal, especially Great Britain and France.

How would they manage their economic and political interests while avoiding conflict? How would the United States and the Soviet Union support Nassar’s quest for Egypt’s sovereignty and Israel? How would Great Britain, France, the United States, Israel, and the Soviet Union manage their own economic and political interests while avoiding military conflict? How would Egypt preserve its national sovereignty?

In this historical scenario, students will have to overcome differing national interests to maintain global security and peace. The exercise will develop skills in leadership, collaboration, composure, analysis, communication, awareness, management, innovation, and advocacy.

Education at NMAD: Resources for Teaching and Learning Diplomacy

Through its educational programs and exhibitions, the National Museum of American Diplomacy promotes public understanding and appreciation of diplomacy and the work of the U.S. Department of State. NMAD aims to inspire the next generation of diplomats who are essential to the ongoing security and prosperity of the United States.