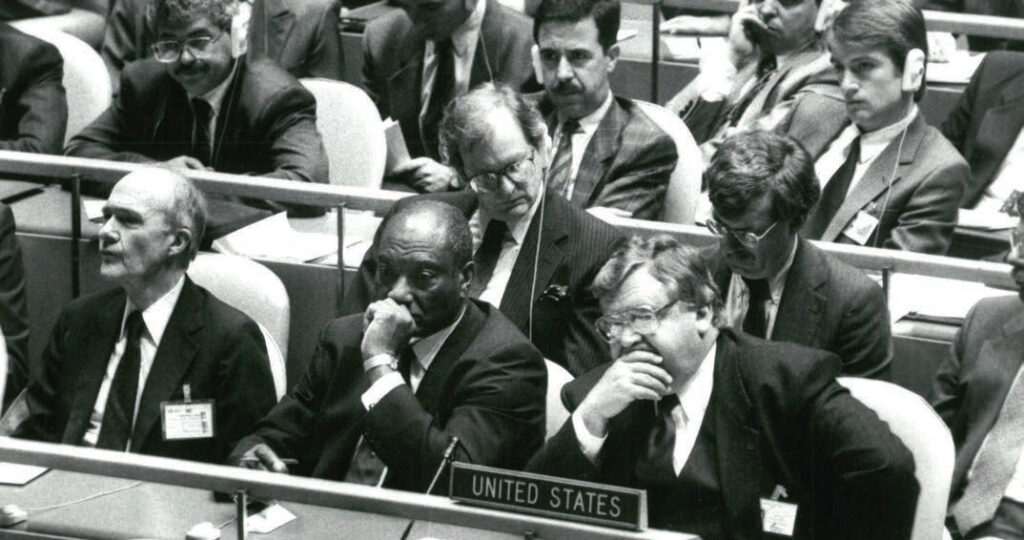

8 Lessons in Diplomacy from Ambassador Edward J. Perkins (1928-2020)

Ambassador Edward J. Perkins knew segregation well. He was born into a segregated and racist society in 1928 on a small farm in the American south. His life took him from segregated Louisiana to a segregated military, to a world filled with anti-Black racism in Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and Thailand. Every part of his journey would prepare him for his monumental role: to be the first Black U.S .ambassador to South Africa. His singular mission, he later related, was to “dismantle apartheid without violence.”

Ambassador Perkins leaves a legacy that inspires diplomats to this day. In his memoir Mr. Ambassador: Warrior for Peace, Perkins shares his life story and diplomatic wisdom.

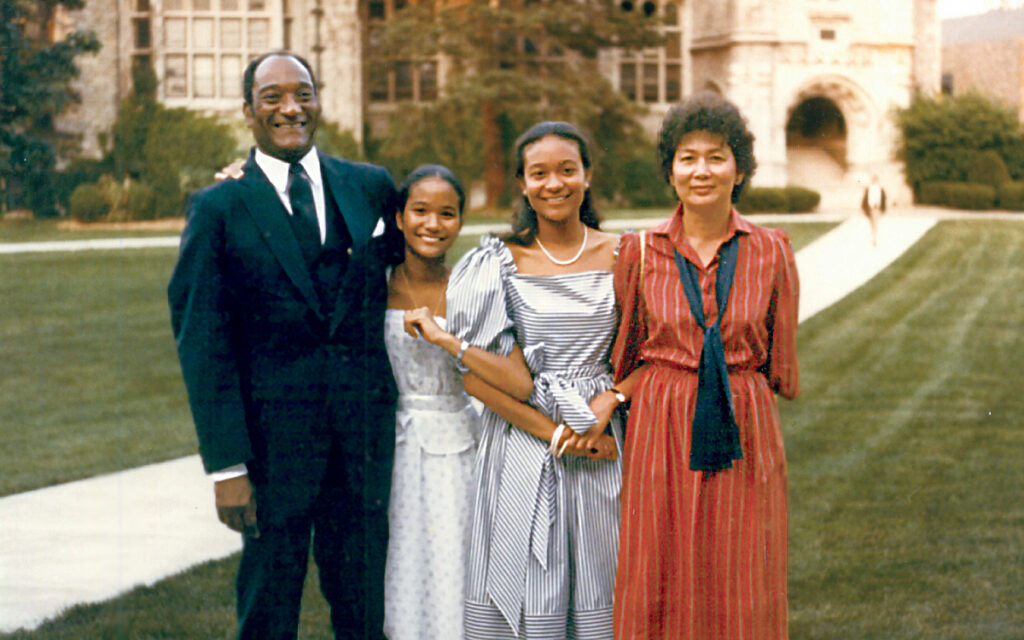

In honor of Black History Month, we pay tribute to Ambassador Perkins by telling his story. We are sharing his legacy through his children, Katherine and Sarah, who will join us for a discussion on February 24th to talk about their life with their father in the foreign service.

In the meantime, here are just a few lessons from Ambassador Perkins on the skills and tools necessary to be a great diplomat.

1) Learn and read everything you can

From an early age, Perkins was an insatiable reader. Although his grandmother was illiterate all her life, she instilled in him a passion for learning. On their farm in Louisiana, she emphasized the importance of education. Every time Perkins would pass a piece of paper on the ground, his grandmother would ask him to read it. He says his grandmother instilled in him a passion and gift of curiosity. “She never once let me believe I was meant for anything but the top,” says Perkins.

The more Perkins learned, the more he wanted to discover. He moved to Pine Bluff, Arkansas to attend high school, living with his mother and stepfather. He later followed his mother to Portland, Oregon to ultimately finish high school. Perkins knew the importance of getting a college education but lacked a way to finance his studies. After high school, he enlisted in the Army, intending to use the GI bill to fund his higher education. Perkins’ colleagues called him the Professor in his military service because he was always carrying books, reading, studying, and learning.

2) Lean on others and do your work for others

Perkins credits his success in education to his curiosity, but also his mentors.

One mentor was Carmen Parrish Walker, a counselor at the Vanport Recreational Center in Portland, Oregon. Carmen was a college-educated Black woman from Mississippi and the only Black member of the staff. He remarks on Carmen’s impact on his life and how it ultimately prepared him to become Ambassador. Secretary Shultz even called Carmen to ask her advice before appointing him as the Ambassador to South Africa. Carmen continued to support and believe in Perkins, saying, “If anyone can do it, Ed can do it.”

While Perkins credits some of his success to his mentors, he also emphasizes the importance of working for others. He said:

“I have an opportunity to do something for myself, but I can never do it for myself alone.“

– Edward J. Perkins

3) Follow the way of the warrior

Quickly after returning from the Army, Perkins was inspired to join the Marines. He looks back on his two years as a marine as some of the best years of his life. While the training was grueling, Perkins says the Marines taught him lessons about self-discipline that he still uses today.

His study of Asian philosophy reinforced these lessons from the Marines. Perkins frequently studied three books: The Art of War by Sun Tzu, The Book of Five Rings by Miyamoto Musashi, and Bushido: A Modern Adaptation of the Ancient Code of the Samurai by Mark Edward Cody.

Perkins frequently quotes this passage from Sun Tzu and has applied it throughout his career: “Be a fish in the river when you are among the people. Swim among them, but do not harm them.” Perkins applied this philosophy to his time as a Foreign Service Officer in Ghana, Liberia, and South Africa.

He calls this philosophy the way of the warrior but replaces his sword with a pen:

“Like a sword, a pen is a way to defend oneself, defend ideas, and defend the nation. My craft is diplomacy, and it is my soul that allows me to believe in the work that I am doing and to attempt to do that work with knowledge, wisdom, mindfulness, and compassion.“

– Edward J. Perkins

Perkins says he learned reserve from his grandfather but personal control through his study of Asian philosophy. He says: “I believe we should not be intrusive or impose ourselves on other people, that a sense of privacy gives one the power to deal with a personal environment, and that personal environment is something that must be controlled.”

4) Learn languages as much as you can

Perkins began to study languages during his military service. He studied Korean, Japanese, and Thai while abroad and later as a civilian officer working for USAID in Bangkok. Perkins was fascinated by languages, saying, “once I find the key, a new culture springs open.”

He believed learning languages helped him become a better listener. In Japan, serving as a soldier, Perkins says by studying Japanese, “I developed the ability to listen intently. Usually, we hear people talk, but instead of listening fully, we are preparing our response.” Perkins said:

“If every officer were required to learn the language of the country in which he served, he would be able to do a much better job.“

– Edward J. Perkins

5) Listen.

Colleagues of Perkins have often noted his strong listening skills. While he said language learning improved his listening skills, he also credits this skill with afternoons sitting on the front porch in Louisiana, listening to his grandparents who raised him for most of his youth. Perkins inherited aspects of his grandfather’s personality and demeanor as well. People call Ambassador Perkins a “quiet giant of man,” but Perkins says that is always how he saw his grandfather.

Listening was essential to Perkins’ diplomatic service. Not just listening to the citizens of where he was posted but the citizens of the United States. Perkins would often turn to his friends and colleagues in Portland, asking for their foreign policy perspectives.

“I sought information and guidance from the nation’s experts and advisors, but I also wanted to hear the opinions of people across the country because I believe that foreign policy is a responsibility not just of professionals but of all citizens.“

– Edward J. Perkins

6) Understand your adversary

Perkins knew the importance of studying and understanding those he would come up against in his career.

In 1972, at the age of 44, Perkins would fulfill his high school dream of becoming a Foreign Service Officer. As a USAID civilian employee in Bangkok, Perkins faced fewer barriers to advance to the oral examination component of the interview. He studied for months, traveled to Washington, DC, and passed.

At the time, there were very few Black foreign service officers. Perkins was determined to make the Foreign Service more representative of America. His colleague, John Gravely, shared this passion. They and eight other Black officers established the Thursday Luncheon Group in 1973. The group still operates today.

Perkins and his colleagues wanted to pitch to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to increase diversity in the foreign service and elevate the status of the Equal Opportunity Office. To formulate this pitch, they started by researching Kissinger himself. In their preparation, they anticipated all of the possible scenarios that may arise. They understood Kissinger’s passion for statecraft and that an argument about resource efficiency would be more compelling than a moral argument. When the delegation delivered their pitch, they were surprised at how quickly Kissinger made monumental changes. Perkins said, “it was one of the most remarkable things I have ever done.”

Understanding others was essential throughout his career. As Ambassador to South Africa, Perkins understood the value of knowing Black South Africans and Afrikaners. Perkins believed that this was the only way they would make progress:

“By understanding [Afrikaners], I reasoned, I could find an opening to slip inside, and from that place, I could begin a discussion. From there, I hoped to dismantle apartheid. Understanding the Afrikaners was key—which nobody in the United States government had ever said before.“

– Edward J. Perkins

7) Don’t let any doors be closed to you

From Louisiana to Portland to Japan, Perkins says he never saw a world without racism, even if it was hidden. What Perkins called the “Twin Dragons,” racism and segregation, were everywhere.

Perkins said his high school mentor, Carmen, never let him forget that as a Black person, he had to excel. She said, “If you set your mind to it, you can do it. Don’t let doors be closed to you.”

In high school, Perkins attended a lunchtime lecture organized by his history teacher in the library. Two Foreign Service Officers from Washington, D.C., spoke to the class about their careers. Perkins recalls listening to the lecture with his classmate, Joy.

“Joy and I were the only minorities in that class, and we realized they were not talking to us as prospective Foreign Service employees, but I was riveted by what they said. From that moment, I was hooked on the foreign service.“

– Edward J. Perkins

As a newly appointed foreign service officer in Washington, D.C., Perkins went to a reception in the Benjamin Franklin Room of the State Department. Chatting with the two other Black men in the room, an elderly woman approached them and said, “Sonny, would you get me a Coke?” He politely directed her toward the bar and noted that this would not be the last time he was mistaken for an attendant.

Perkins married Lucy Cheng-Mei Liu after they met in his office in Taiwan. They faced racism throughout their courtship and marriage. He has two biracial children, Katherine and Sarah, who are both fluent in Chinese. In facing racism, Perkins told his children:

“You represent what our country thinks it stands for —that we are a diverse society, made up of people from all nations. Be proud of your heritage and be proud of your citizenship. You are true Americans. Stand up proudly. Hold your head high. And if people give you a tough time, push them out of the way. Keep going. You do not have time for people like that.“

– Edward J. Perkins

8) Be a revolutionary

A successful Foreign Service Officer must be “daring, confident, curious, and love continuous education,” says Perkins. He also said that diplomats should be, at heart, revolutionary:

“How does one be an effective change agent as a Foreign Service officer? It seems to me, as it was proven to me in South Africa, that one must be a revolutionary at the bottom of one’s heart before beginning to use the tendency toward revolution as a foreign policy too. Why did I challenge the status quo, ostensibly without fear or concern for my career, and why did I go to South Africa? Because I believed in what was being attempted by the different groups: to overthrow the regime in a revolutionary sense. So one must become a revolutionary at heart in order to make it work for the United States.“

– Edward J. Perkins

By believing he could make a change and carrying these skills and tools of diplomacy, Ambassador Perkins made a lasting impact on the world.

Watch our discussion with Katherine and Sarah Perkins: Ambassador Edward J. Perkins: Reflections on Families in the Diplomatic Service

Further Reading

Perkins, Edward Joseph. Mr. Ambassador: Warrior for Peace. University of Oklahoma Press, 2006.

American Foreign Service Association (AFSA). Pioneer, Bridge Builder and Statesman—A Conversation with Ambassador Edward J. Perkins. Foreign Service Journal, 2020.