Ambassador Mari-Luci Jaramillo: The First Hispanic American Woman Ambassador

Mari-Luci Jaramillo was a renowned educator who served as Ambassador to Honduras under Carter’s administration from 1977-1980.

Jaramillo started her career as a teacher but quickly grew her leadership skills to push education reform and civil rights at a national and international level.

Her popularity in various communities led President Jimmy Carter to nominate her as Ambassador to Honduras in 1977, making her the first woman Hispanic American Ambassador.

Although Jaramillo did not have prior experience in foreign affairs, her consistency and drive to learn from the embassy staff and Honduras made her a much-loved ambassador.

An Expectation of Edification

A native New Mexican and daughter of laborers, Mari-Luci Jaramillo was a studious and ambitious child.

Jaramillo’s father immigrated from Durango, Mexico, around 1910 with a fourth-grade level education, self-taught English, and several trades and skills. He provided for his family through his shoe business.

Jaramillo’s father passed on his love of education to Mari-Luci and her siblings. The children were expected to receive excellent grades. Their mother also prioritized education above housework and wanted to give them the best home environment possible.

Although Mari-Luci Jaramillo graduated high school as valedictorian with academic awards, her family’s financial situation made attending university a distant hope. Jaramillo went above and beyond to pay for her education by working at her father’s shoe shop, a parachute factory, tutoring students, waitressing, and other jobs she could find.

By 1970, Jaramillo completed her undergraduate and master’s degrees at New Mexico Highlands University and earned her doctorate from the University of New Mexico.

While completing her degrees Jaramillo expanded her career as an elementary school teacher by being invited to join the faculty of the University of New Mexico where she became involved in several programs in Latin America.

As a Hispanic American educator, Jaramillo was passionate about the importance of bilingual education for the Hispanic communities in New Mexico. While prioritizing formal English was important for students to rise out of poverty, Jaramillo encouraged bilingual education to preserve the Spanish language and culture for these communities.

Her innovative teaching methods to teach bilingualism and multiculturalism made her a popular speaker and activist throughout the United States, Latin America, and Europe, including working with U.S. military groups abroad on ways to address discrimination in the armed services.

From Educator to Ambassador

Being appointed as Ambassador to Honduras came as a surprise to Jaramillo. She received the call from then-Deputy Secretary of State Warren Christopher to serve in President Carter’s administration. She was not active in politics but was excited by how Carter spoke about human rights and the hardships of the poor at a national level.

Like all Ambassadorial candidates, Jaramillo needed to defend her nomination through a Senate Confirmation hearing. Jaramillo prepared diligently for the hearing. She was determined to prove her qualifications despite disparaging comments from some Senators. Jaramillo recalls,

“I remember…the last question was: ‘And what makes you think that you could be an ambassador? You’ve only been a school teacher?’, and that made me mad…I came back, and I said, ‘…a teacher learns to work with many, many people of diverse backgrounds; and you have to focus it so that you come out with a common purpose.‘”

– Ambassador Mari Luci Jaramillo

As the first Hispanic American woman to serve, Jaramillo understood the pressure and importance of being a pioneer, commenting:

“You’re conscious of it every single day; that whatever you do means another woman comes or another woman doesn’t.“

– Ambassador Mari Luci Jaramillo

An Ambassador’s Guide to Relationships: Personalize Everything

As Ambassador, Jaramillo strongly believed in getting to know her embassy community, the people of Honduras, and her foreign diplomatic colleagues.

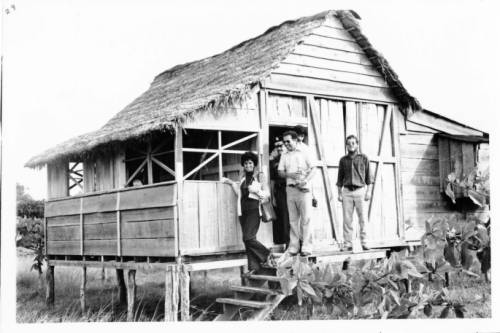

She often held receptions at her residence and would rotate staff to attend occasionally to get to know everyone. Jaramillo truly believed in the work of the Peace Corps in the country and wanted the Honduran government and people to recognize and support their efforts. She often invited Peace Corps volunteers to the Ambassador’s residence to thank them for their service and to demonstrate that she personally valued their work.

Jaramillo recalls having two young Peace Corps women over. She did not hesitate to introduce them to her guests, including the Honduran president.

The volunteers were grateful for her attentive hostessing. One woman confessed to Jaramillo that they did not expect the American Ambassador to give them any attention. Jaramillo responded, “…I don’t blame you for thinking that. If I’d been in your shoes, I would have thought that, too. I’m so glad that you found out that I really do mean [what] I say.”

Diplomacy in Action: Advocating for U.S. Aid from Within

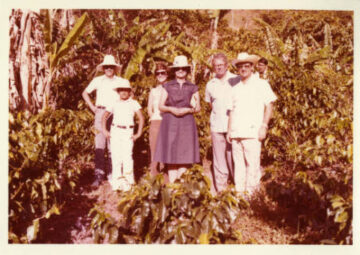

Jaramillo made it a point to travel throughout Honduras to support the various U.S. government-funded programs and projects. From road construction projects to supporting local Peace Corps volunteers, Jaramillo understood the importance of her presence and personalized interactions.

A local woman presents a gift to Ambassador Mari-Luci Jaramillo in Sulaco, Yoro, Honduras. Photo courtesy of the National Hispanic Cultural Center Library and Archives.

Ambassador Mari-Luci Jaramillo (center) admiring the Quetzal feathers presented to her in Sulaco, Yoro, Honduras. Photo courtesy of the National Hispanic Cultural Center Library and Archives.

Jaramillo and her husband, Heriberto Jaramillo (left), visit a shrimp business owner. Photo courtesy of the National Hispanic Cultural Center Library and Archives.ion

Ambassador Mari-Luci Jaramillo cutting chicken with workers at a meat processing plant in Danli, Honduras. Photo courtesy of the National Hispanic Cultural Center Library and Archives.

Ambassador Mari-Luci Jaramillo and Honduran officials at the inauguration of a new USAID-funded road in Suyapa Frontera, Honduras. Photo courtesy of the National Hispanic Cultural Center Library and Archives.

A Legacy of Public Service for Hispanic American Women

Jaramillo left Honduras with many friends and memories in all circles of Honduras. The Honduran government awarded her the Order of Francisco Morazan Medal, the highest award that can be given to a foreign dignitary in Honduras, but they didn’t stop there. In a private ceremony, she was granted a rare Dual Citizenship Award for her extraordinary achievement in Honduras, which she treasured greatly.

Jaramillo served as Deputy Assistant Secretary for Latin American Affairs for a few months until Ronald Reagan won the presidential election in the fall of 1980. She returned to her hometown of Albuquerque, New Mexico, where, over the years, she hosted several Honduran delegates that sought her out when visiting the United States.

Jaramillo continued to advance her career in education; she wished she could have contributed more to international affairs. She was able to rejoin the diplomatic community once more as Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Latin America in 1992 under the Clinton administration. She passed away at the age of 91 on November 20, 2019.

Sources Consulted

Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Oral History Interview