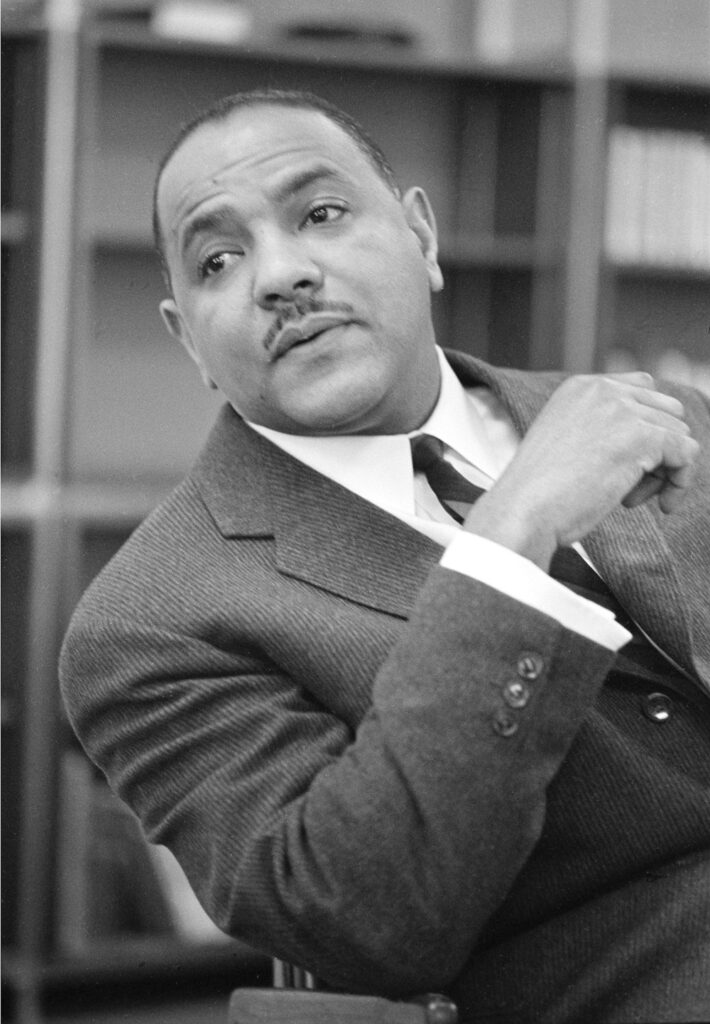

Carl T. Rowan: From Journalist to Diplomat

The path to becoming a diplomat is not always obvious. For Carl T. Rowan, he paved his path with his storytelling.

His many articles on racism in America and international affairs caught the attention of President John F. Kennedy, propelling him into multiple political appointments.

In 1961, Rowan became the highest-ranking Black American in the State Department. After gaining the trust of President Lyndon B. Johnson, he served as Ambassador to Finland and Director of the U.S. Information Agency.

Throughout his career, diplomatic and otherwise, Rowan’s diplomatic skill of communication separated him from others. He is an example of how communicating well can pave the way for an influential diplomatic career.

Communicating to the Public About Racism in America

Carl Rowan rose to fame as a reporter for The Minneapolis Tribune. His series “How Far From Slavery?” was wildly popular, spreading across the country.

In this series, Rowan details how Black Americans lived and were treated in the American South after World War II. In his memoir, Rowan recounts instances of the racism, discrimination, and threats he faced on his six-week journey doing research for the series. At the time, the Minneapolis Spokesman said that these articles “make a contribution to helping make America free in truth as well as theory.”

Communicating American Ideals to India

Rowan’s expert storytelling made him an ideal candidate for the State-Department’s Leader-Grantee program. Through the program, Rowan lectured crowds all over India about issues of the day.

Multiple Black Americans participated in these government trips. But the United States faced a dilemma in the war of ideas. America claimed to stand for ideals of freedom and democracy, but at home, Black Americans were treated as second-class citizens.

Rowan spoke optimistically, then, about the future of race relations in America. In his 1991 memoir, he says:

“I was still naively optimistic about the willingness of the South to accept the end of Jim Crow. It had not dawned on me that even Boston and Pontiac, Michigan, would become embroiled in violence as white parents sought to keep their children from going to school with black youngsters. I was not a State Department lackey. I assailed racism and racists whose names were known to the Indians in my audiences. I simply went from Darjeeling to Patna to Cuttack to Madras, saying good things about my country because I believed that the society that had given me a break was in the process of taking great strides toward racial justice.”

Rowan Becomes the Highest Rank Black American in the State Department

The more Rowan wrote the more his fame grew. He went on to cover major international events such as the historic Asian-African Bandung Conference in 1955 and the Suez Canal Crisis at the United Nations. He was on a first-name basis with everyone from Eleanor Roosevelt to Martin Luther King Jr. He interviewed the most influential people in America, including Presidents Harry S Truman, Richard Nixon, and John F. Kennedy.

Rowan’s interview with Kennedy took place during his 1960 presidential campaign. Rowan’s work made such an impression that in 1961, President Kennedy asked Rowan to join his administration.

At first, Rowan was offered the role of State Department spokesman. His close confidant Hubert Humphrey urged him not to accept anything lower than Deputy Assistant Secretary of Public Affairs. Rowan followed his advice—his counteroffer was accepted within the hour.

Rowan was responsible for communicating President Kennedy’s policies on foreign affairs and to explain why those policies were in the interests of the American people. In his role, he faced regular discrimination and racism within the State Department:

“I learned quickly that the State Department was a virtual plantation. There were many blacks in State but they were the messengers, the janitors, the low-paid secretaries and clerk-stenographers, the mail clerks and the clerk typists.”

– Carl T. Rowan

In the face of these challenges, Rowan does recount making some progress. He brought Black publications into the Public Affairs Bureau and also helped increase the pay of some of his Black colleagues. However, he left his position pessimistic about how quickly the culture could change. He said in his memoir, “Despite little concessions like these, I knew that I had walked into a hostile environment, into a State Department that was not properly educated to deal with the new world that was emerging out of the carnage of the worst war man had ever known.”

Outside of Washington, Rowan traveled the world with Undersecretary of State Chester Bowles. His previous work covering international events gave him clout. Still, he had to constantly prove himself to other diplomats as a Black man.

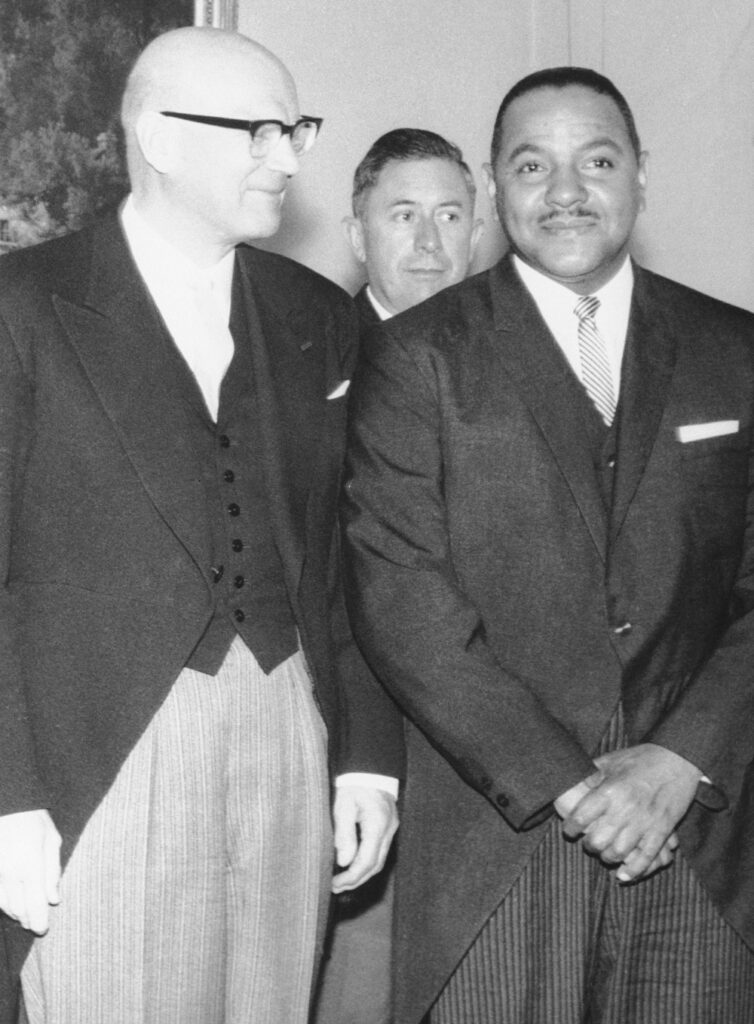

His most significant trip was in 1961 when the State Department asked him to accompany Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson on a trip around the world. In his memoir, Rowan describes Johnson as “egocentric, domineering, imperious, mean, insecure, cornpone, unfaithful, crude. He was also generous, brave, a fighter for the little guy, loyal to friends and causes—and damned effective.” Nevertheless, by the end of the trip, Rowan and Johnson cemented a friendship and trust that would last for the rest of their lives.

Rowan faced the challenging task of communicating to the Vice President what he didn’t want to hear. For example, Johnson was not speaking to the press corps following their travels. Johnson then complained about a frivolous article published by one of the journalists. In response, Rowan said, “Mr. Vice President, I am not your press secretary, but since you have come to me I am going to speak to you in that role. Their publications have spent a lot of money to send them. These reporters are going to file stories every day. If you give them some facts, something specific, they’ll write about that. If you give them nothing they’ll write thumb-suckers and think pieces.” Rowan ultimately convinced Johnson to speak more with the press.

Carl T. Rowan Appointed U.S. Ambassador to Finland

Rowan’s ambassadorship to Finland came about when Rowan received a lucrative job offer in journalism. Determined to keep Rowan in public service, President Kennedy offered him an appointment as Ambassador to Finland in 1963.

The Finnish media were preoccupied with his race. One magazine called him “The Most Colorful Ambassador in Helsinki.” Women’s magazines wrote article about his wife’s skin color. Yet Rowan made headway in advancing America’s interests and communicating the country’s ideals to Finland. Rowan reflected:

“My judgment was that I could tap into this trust for America, this distrust for Moscow, this love for most of the things the United States stood for, with speeches that went beyond what previous ambassadors dared to say.”

– Carl T. Rowan

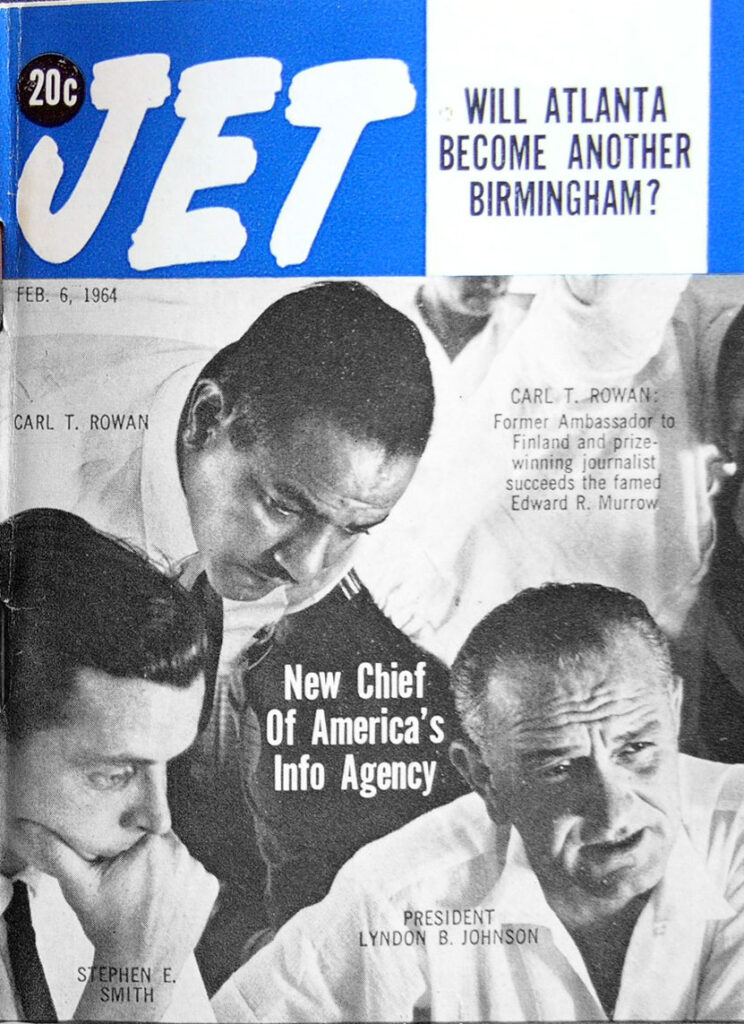

Director of the USIA: Telling Stories of America to the World

On November 22, 1963, President Kennedy was tragically murdered on a trip to Dallas, Texas. Rowan had met with the President two days prior, where Kennedy shared his worries about rising racial hatred in America.

Upon becoming the new President, Johnson was determined to make civil rights progress. He told Rowan as much in a meeting soon after Kennedy’s death. Their meeting sparked rumors of Rowan becoming part of Johnson’s administration. These rumors turned true when Johnson called Rowan in January 1964, saying, “Come home, Carl, I need you.”

On February 28, 1964, Rowan became the Director of the U.S. Information Agency (USIA), replacing Edward R. Murrow because of his poor health. In this role, Rowan was responsible for supervising a global network of news outlets, exchange programs, and libraries. He also had a literal seat at the table, as Johnson made his position part of the National Security Council.

Over time, the President diverted Rowan’s attention away from USIA’s primary goal. Rowan spent more and more time and resources of the USIA on the impending war in Vietnam.

In one example, Johnson asked Rowan to try to get a million-watt medium-wave transmitter installed in Southeast Asia. Johnson was sure this would help them win over hearts and minds regarding the United States’ role in Vietnam. Rowan knew the U.S. government had tried for five years to get this transmitter, but Johnson didn’t care. Rowan went out on a limb to make the transmitter happen, but in the final hours, Johnson wouldn’t let Rowan go to Bangkok to seal the deal. Johnson was paranoid about letting top aides leave while he was under such scrutiny regarding the war. Rowan was furious, saying he had put “his honor on the line with Thailand’s Foreign Minister.”

Frustrated by a lack of communication from the President and contradictory directives, Rowan resigned in July of 1965.

Rowan would go on to continue his illustrious journalism career until his death in 2000. In the field of diplomacy, Rowan will always be known for his pioneering advancements, his powerful words, and his commitment to service.

For Further Learning

Rowan, Carl T. 1991. Breaking Barriers: A Memoir. Boston: Little, Brown.

Watch The American Diplomat | American Experience | Official Site | PBS