Raymond Telles: America’s First Hispanic-American Ambassador

Raymond Telles was America’s first Hispanic-American ambassador, serving in Costa Rica (1961-1967) amid the Cold War during the John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson presidencies.

Telles displayed a natural talent for diplomacy. His compassion, dedication to serving the United States, and strong leadership qualities strengthened relationships with the people and leaders of Central America.

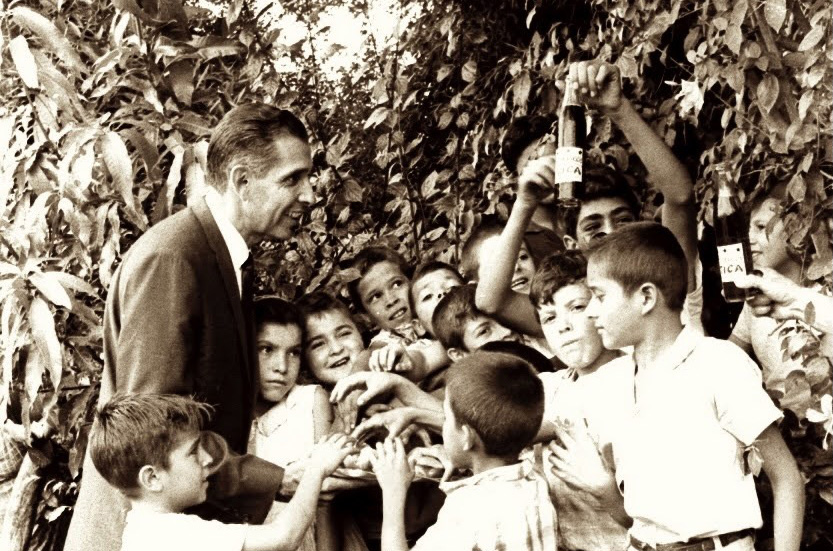

He accomplished this with a grassroots style of diplomacy generally unheard of for ambassadors of the time. He insisted on being among the people and became a role model for young Latinos everywhere.

“He created a standard that younger Latinos were able to see and follow and that senior American political figures took as an indication of what the Latino community could bring and offer.”

Former Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Henry Cisneros

Raymond Telles’s Humble Beginnings and High Aspirations

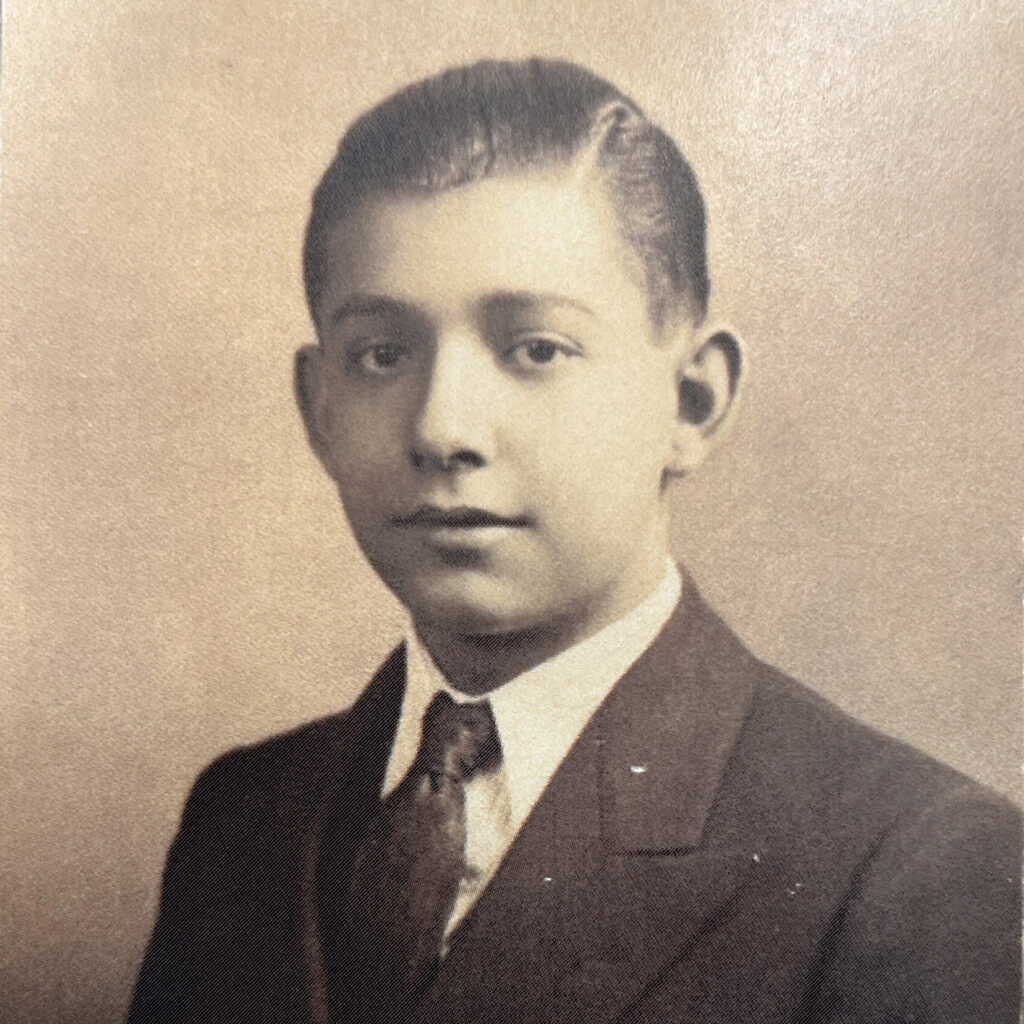

Raymond Telles was born in 1915 in the Mexican American neighborhood of El Segundo Barrio in El Paso, Texas. His father, Ramón, began as a bricklayer, and his mother, Angela, ran their little neighborhood grocery. It was a tough neighborhood, and Ramón taught his son to box should he need to stand up for himself.

Despite the financial hardship brought on by the Depression, the Telleses enrolled Raymond in a private Catholic school mostly attended by white children. He shined shoes and delivered newspapers to contribute financially. A brilliant student, he displayed a sense of humility and a belief that he wasn’t better than anyone else. He carried these skills his entire life.

After graduating high school, Telles earned an Associate’s degree in accounting at El Paso’s International Business School. He landed a job with the Works Progress Administration and advanced to a leadership position. In 1939, Telles found a better-paying clerk job in the federal prison system and took night classes at the University of Texas at El Paso. But, his aspirations did not end with higher education and improved financial security. He wanted to serve his country and his Latino community.

Serving the Nation and Natural Leadership

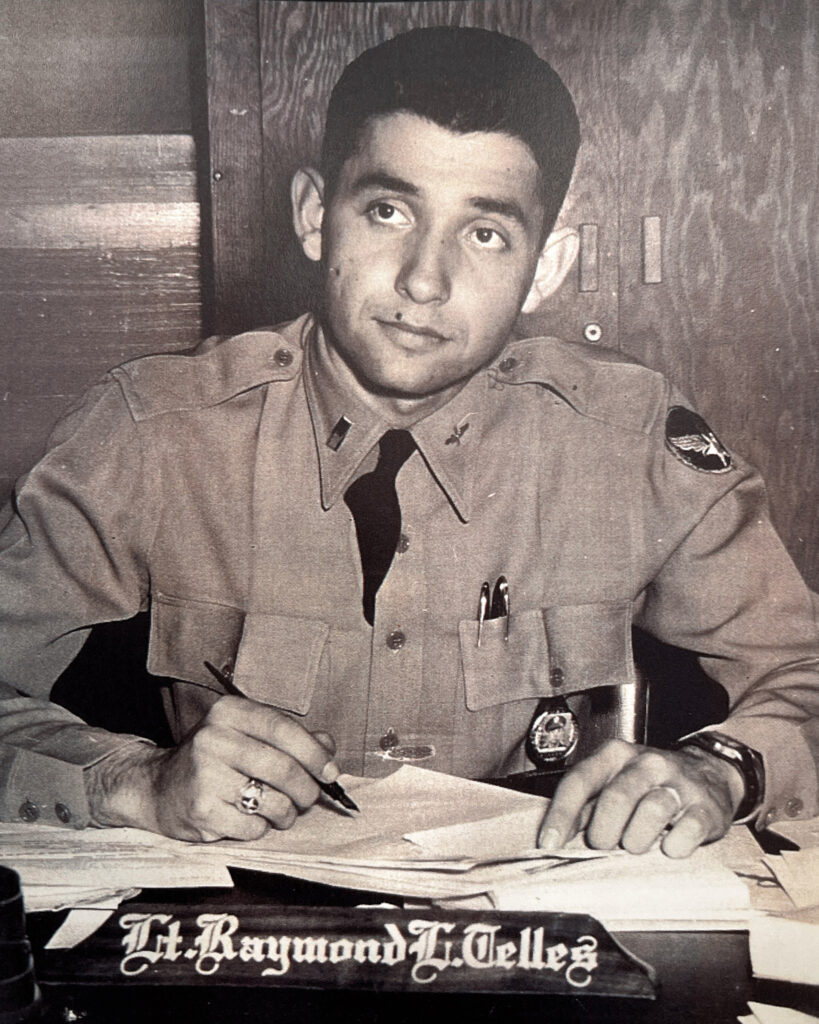

Telles volunteered for the military in 1940, entering as a private, and was assigned to Fort Bliss, Texas. Superiors quickly recognized his natural leadership, intellect, and organizational skills. Within six months, he had risen to Technical Sergeant and chief supply clerk. When the United States entered World War II in December 1941, his skills were needed more than ever.

Believing he would be sent overseas, Telles married his sweetheart, Delfina Navarro, in 1942. However, the U.S. Air Force desperately needed Spanish speakers to remain in the United States to aid Latin America during the war, and Telles was bilingual. First, he went to officer training school, and then, as a Lieutenant, was assigned to Kelly Field, Texas.

Of the estimated 350,000 Latinos who served the United States in World War II, few held leadership positions. With his elevated rank and responsibilities, Telles became Chief of the Lend-Lease program for Central and South America. These regions suffered significant economic hardship when the war disrupted trade, and protecting the security of the Panama Canal was of utmost importance.

In this position, Telles honed his diplomatic skills. He managed relationships with the military and leaders of foreign nations while helping to protect the citizens of those countries. Under his leadership, the U.S. Air Force sent one thousand planes from Mexico to Brazil, and Telles organized training programs for foreign officers, for which he was later decorated by many Latin American governments. At the war’s end, he was the chief liaison officer between the Mexican and U.S. governments and served as an aide to General Dwight Eisenhower. Later, he achieved the rank of colonel in the U.S. Air Force Reserves.

Telles Leads the Charge for Change and Social Justice

After World War II, Telles returned to El Paso, determined to effect change. His service in the military as a proud Latino had helped defeat authoritarianism. The contributions of women and minorities to the war effort meant there would not be a return to the pre-war discriminatory status quo.

Telles wanted to tackle social injustice. He ran for county clerk in 1948, making voter registration a major issue in his candidacy. Citizens were required to pay a poll tax before they could register to vote, and many financially insecure Mexican Americans in El Paso could not afford it. With help from his brother as his campaign manager, Telles organized fund drives to help pay the poll tax, increasing voter registration.

He was the underdog candidate and was victorious against the opposition’s ugly racist attacks. In office, Telles broke down systemic racial barriers to civic participation and served four successful terms. Recalled to military service during the Korean War, he was even more determined to effect greater change upon his return home.

By the mid-1950s, organized civil rights movements were sweeping America. Telles believed he could make a bigger difference as mayor of El Paso. He once again defeated racist political attacks and won the mayorship as the Democratic candidate. His celebrated success made him the first Hispanic-American mayor of a major U.S. city. His election opened a door of opportunities for Latinos to run for public office. This was especially momentous as white Democrats across the South resisted demands for desegregation, and racist groups terrorized minority voters.

As mayor, Telles strove to fulfill all his promises: to desegregate El Paso’s public spaces and help provide equal opportunity for all, opening the doors to city employment, including the police and fire departments, for the first time. He was not afraid to challenge racist businesses, which often held great influence in city politics.

The Plaza Theater in downtown El Paso was an example of public segregation. Even though El Paso did not adopt ordinances to ban segregation until after Telles departed for his ambassadorship, while mayor he ordered the city’s movie theaters to integrate. When management of the Plaza Theater refused, Telles had the police padlock the theater doors. It was then that management paid attention! The Plaza was desegregated shortly afterward.

Raymond Telles: The First Hispanic-American Ambassador

By 1960, Telles was a rising star in the Democratic Party. When John F. Kennedy ran for president as the Democratic candidate, Telles enthusiastically supported him and campaigned for him in Mexican American communities throughout California and Texas. When Kennedy won the presidency, he appointed Telles ambassador to Costa Rica.

Telles and Kennedy hit it off immediately. Kennedy’s Latin American foreign policy goals promoted democracy and economic growth to deter communism. This resonated with Telles. Further, they shared humanitarian principles and a belief that strong relationships with foreign nations were built by interactions with the people—not just politicians. Moreover, Telles was bilingual and sharp in economics. All these qualities made him a natural choice.

Telles and his family, now with two young daughters, set out for his ambassadorship in 1961.

“In addition to dealing with the government, I used the people’s approach more than anyone else had ever done in the past. I did it, not only because President Kennedy had instructed me to do so, but because I felt this was the way to make friends with these people for our country, by direct contact.”

Ambassador Raymond Telles

Telles’s diplomatic approach is now a common practice in public diplomacy work. But in 1961, this was an unusual method for ambassadors. On his arrival, his deputy did not agree with Telles going out to meet the people and tried to undermine him. Telles didn’t allow the insubordination and sent the deputy back to Washington, DC.

“I had a few problems when I came [to Costa Rica] because being a presidential political appointee, and I was from a different party that had been in power, and the fact that I was using the close contact approach with the people,” said Telles. “This wasn’t the way that career diplomats operated. They wanted the ambassador to remain in his ivory tower and never be seen but respected because he was the U.S. ambassador. I felt entirely different.”

Press taking photos of U.S. Ambassador Raymond Telles (left) presenting his official credentials to the Costa Rican president, Mario Echandi Jiménez (right, holding papers) in 1961. Echandi was president from 1958-1962, and Telles immediately established a good relationship with him.

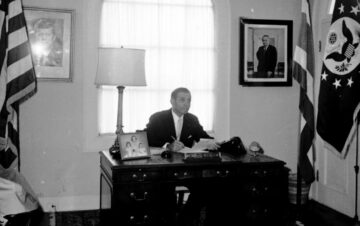

Telles at his desk in the ambassador’s residence in Escazú, Costa Rica, 1962. Photo courtesy of Ambassador Cynthia Telles.

Ambassador Telles Receives a Presidential Visit

Kennedy’s cornerstone foreign policy platforms for Latin America were the Alliance for Progress (Alianza para el Progreso) and support for the Central American Common Market (CACM).

The Alliance was an economic cooperation and development plan to improve infrastructure, designed to lift people out of poverty. It was largely funded by U.S. government loans. It stood in stark contrast to the restrictions and suppressions on countries such as Cuba, which relied on the Communist system and the Soviet Union. The CACM was a regional cooperative agreement meant to break trade barriers and promote Central American exports.

Telles passionately advocated for the people and frequented remote villages to see what they needed. Although the CACM was founded in 1960, Costa Rica did not become a member until 1962 after Telles persuaded its president to join. The Alliance for Progress thrived under Telles’s leadership, constructing new housing and schools during his tenure as ambassador. Notably, Telles was instrumental in helping establish Costa Rica’s first medical school. He facilitated aid, which provided training from U.S. doctors.

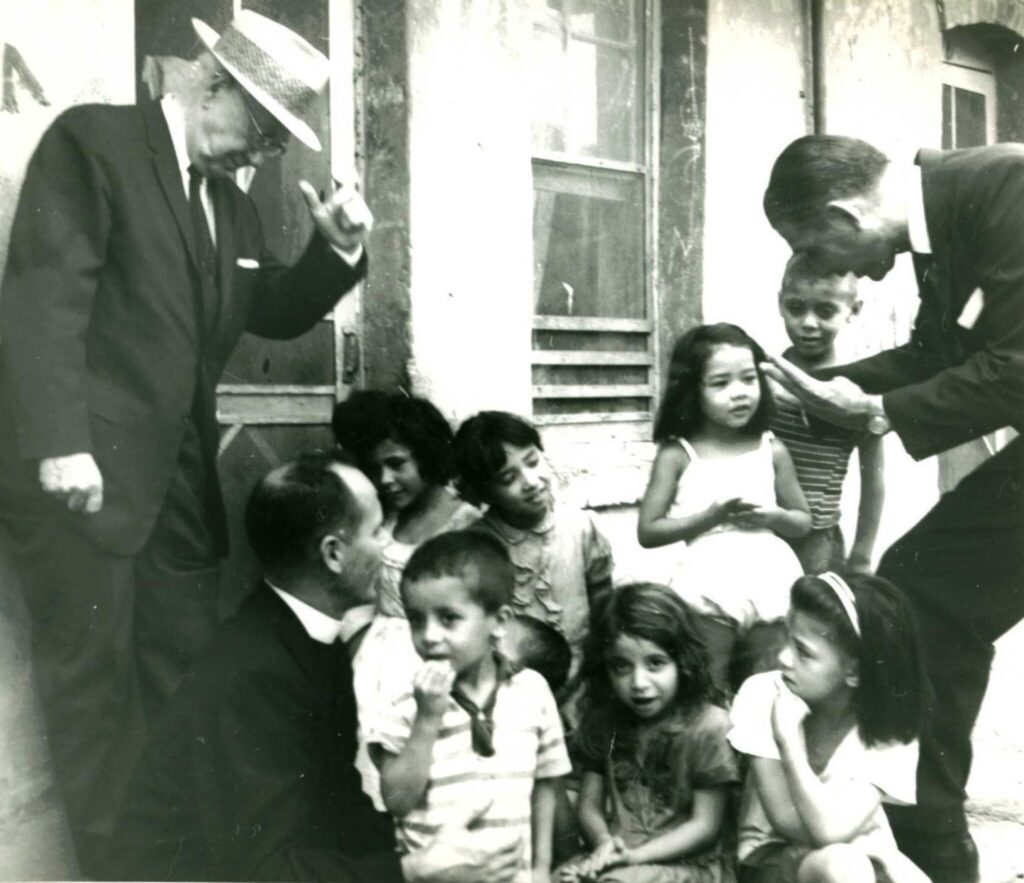

With Telles’s urging, President Kennedy made an official state visit to Costa Rica in March 1963. Telles arranged a meeting with all the presidents of Central America, including Panama, which had never happened before. All agreed to continue cooperative efforts under the Alliance for Progress and the Common Market.

Telles also wanted JFK to meet with ordinary citizens who were enamored with the young Catholic U.S. president. JFK’s security refused to allow it. Telles snuck JFK aside and persuaded him to attend a public mass and a university. “Young people would be the future leaders of the county,” he told him, “and peace and friendship with our country would be in their hands.”

JFK overruled his security team, which meant Telles was on the hook if something bad happened. At the university, with unfriendly communist students in the crowd, JFK made a well-received speech about the importance of democracy. His team struggled to keep students from getting too close and were exasperated when JFK insisted on wading through the crowd to shake hands.

Next, JFK inaugurated an Alliance for Progress housing project and again insisted on meeting the locals. Kennedy ducked through alleys to avoid his security to meet a large crowd. Later, when Kennedy departed on Air Force One, Telles breathed a sigh of relief. Before leaving, the President teased him, saying, “It’s a damn good thing that everything went off all right down there.”

President Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963. Telles’s daughter, Cynthia, remembers seeing her father cry for the first time. The Costa Rican people went into mourning, and Telles arranged a funeral mass. He also met with people who came to the embassy to express their condolences. An impoverished woman handed him money, no more than a few dollars, imploring him to send it to Mrs. Kennedy. “Now that she lost her husband,” she said through tears, “she will have so many expenses.”

A Friend In Times of Trouble

Ambassador Telles’s close connection with the Costa Rican people went far beyond promoting democracy and economic development. In March 1963, Costa Rica’s Irazú volcano began an eruption that lasted two years. Volcanic ash buried and devastated agriculture. The natural disaster hit the poorer rural regions particularly hard.

Irazú’s ashfall proved deadly. In December 1963, the Reventado River carried a massive avalanche of volcanic ash, sweeping away livestock, killing dozens, and burying hundreds of homes in Cartago village. Telles led a search and relief effort and contacted President Lyndon Johnson for aid. Within days, U.S. Seebees arrived with heavy machinery to clear the earth and rebuild homes. Grateful residents later renamed their town “Ciudadela Raymond Telles” in appreciation.

A Different Kind of Cold Warrior

Telles’s diplomatic people-to-people diplomacy came with personal danger. Communist elements in Costa Rica sought to undermine democracy and the United States. But one day, the “commies,” as Telles called them, congregated on the embassy steps and pounded at the door. Striding out, he told the protestors to demonstrate on the street, not on U.S. property. As the United States was a democratic country, they could “sing and shout,” but once they were done, he was going to respond.

Telles calmly said a few words about patriotism and common sense. Then one of the leaders shoved him.

“I grabbed him by the shoulder and pushed him down, and I told him in no uncertain terms, ‘The next time you do this to me, the next time you push me, you’re going to come out missing your teeth.” Once he regained his composure, Telles saw he had to de-escalate the growing scene.

Telles invited the Communist leaders inside to discuss their complaints. Completely bewildered and not expecting a meeting with the U.S. ambassador, they ended up having little to say. He managed to disarm Communists with words.

New President, New Diplomatic Role

In 1967, President Lyndon Johnson tapped Telles for a new important role–Chair of the U.S.-Mexico Border Commission. The purpose of the Border Commission was to work towards cooperative economic and social development of the border areas. Telles was not as close with Johnson as he had been with Kennedy, but the two had a mutual respect for one another and, over time, developed a friendship.

Of Mexican descent, a previous mayor of a border city, having a close personal friendship with the Mexican president, and an understanding of the Mexican people, Telles was well suited for the role. He had also served as a consultant on the Chamizal issue, a disputed border area going back to the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. In 1964, the United States agreed to cede the territory back to Mexico, and Telles helped facilitate the 1967 transfer in his new role.

Telles attributed his diplomatic success to working on the presidential level. He reported directly to Johnson and his counterpart directly to the Mexican president. He and his counterpart had to work together and resolve problems, then take solutions to their presidents. When Hurricane Beulah hit south Texas and north Mexico, together they solved many problems and saved many lives. They also resolved an international assistance agreement that the State Department had been working on for ten years.

Ambassador Telles Championing Equality in All Administrations

Telles left the Border Commission in 1969 during the transition to Richard Nixon’s Republican administration. But, he continued his public service and commitment to equality in a domestic role. Struck by Telles’s accomplishments, Nixon appointed him Chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) in 1971.

While the two shared little politically, during Nixon’s troubled times, he often turned to Telles for companionship. Telles treated the beleaguered president with kindness as the two discussed football in the Oval Office. Telles remained head of the EEOC after Nixon’s resignation, and President Gerald Ford reappointed him. When Telles left the EEOC in 1976, he had served under five U.S. presidents.

Remembering the Compassionate Ambassador

Today, many Costa Ricans still remember Ambassador Raymond Telles. They remember his warmth, compassion, and down-to-earth personality. For someone who had achieved so much personal and career success, what perhaps made Telles so successful as a diplomat was his humility and remembering his roots.

His daughter Cynthia, following in her father’s footsteps as U.S. Ambassador to Costa Rica, shared an example.

The ambassador’s residence in Costa Rica was in a rural area with a small church about a mile away with few parishioners. As devout Catholics, the Telles family regularly attended church there. One day, the priest was frantic because the altar boy had not come. Without him, the priest could not perform mass. Trained as an altar server from his days in El Paso Catholic school, the ambassador volunteered to serve mass with the priest. Ambassador Cynthia Telles said this became a tradition. If the country people wanted to meet el embajador Telles, they could come to church and see him in a suit and tie, kneeling, ringing the bells, and helping with communion.

Acknowledgments

NMAD wishes to thank Dr. Mario T. Garcia, Distinguished Professor of Chicano Studies and History at the University of California Santa Barbara, Ambassador Cynthia Telles, and Joseph Waz for their assistance.

Sources Consulted and For Further Reading

Mario T. Garcia, The Making of a Mexican American Mayor: Raymond L. Telles of El Paso and the Origins of Latino Political Power (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 2018).

8 August 2024 Phone Interview with U.S. Ambassador Cynthia Telles

Telles, Raymond L., Oral History, 1970, JFK Library

Oral History Transcript, Raymond L. Telles, 1972, LBJ Library Oral Histories

A First For Latinos: Remembering Raymond Telles

Texas State Historical Association: Telles, Raymond L. Jr. (1915-2013)

Following in Her Father’s Footsteps, U.S. Ambassador Cynthia Telles

CDC Files: Observations on Air Pollution; Aspects of Irazú Volcano, Costa Rica (1964)