The Declaration Heard ‘Round the World

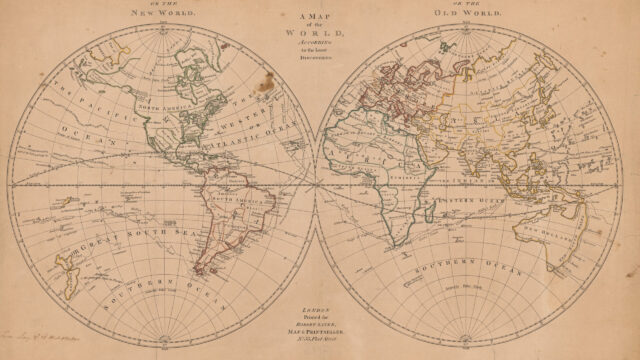

The 1776 Declaration of Independence is one of the most universally well-known historical documents. American diplomats continue to promote the democratic values enshrined in its words to this day. But many people don’t think of it as also being the United States’ first foreign policy document.

While the Declaration was intended to justify to Americans the need to form a separate and independent nation from Great Britain, it was also, as John Adams later wrote, “…a formal and solemn announcement to the world, that the colonies had ceased to be dependent communities, and become free and independent States.”

The Declaration explained to global audiences that this “rebellion” was no civil war between Britons. Rather, it was a pronouncement that the United States intended to join and engage with the world as an equal, sovereign nation. American leaders quickly sent copies to European nations and it was translated into many languages and widely distributed.

The American Revolution that followed the Declaration began a chain of independence movements lasting over 200 years and continues today. Many new nations have used the Declaration as a model framework or as inspiration. Others have used the words in this founding document in their diplomatic appeals to the United States, asking that it live up to its professed democratic values.

The Declaration and the United States’ First Treaty

International audiences included sovereign Native American nations. To win independence, the Americans needed to explain the break from the British Empire and why they needed their recognition and help.

Just days after Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, the United States signed the Treaty of Watertown with the Maliseet and Mi’kmaq nations of present-day New England and Eastern Canada. A translation of the Declaration of Independence was read aloud before the signing. The treaty promised mutual aid and respect for each nation’s sovereignty and remains in force to this day.

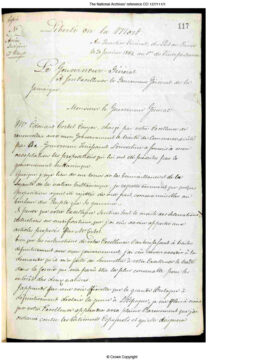

Haiti’s Declaration of Independence Creates the World’s First Black Republic

The 1804 Haitian Declaration of Independence was the first in the Western Hemisphere, modeled after the American Declaration. It stated the intention to create the first independent Black republic in the world, following a successful years-long revolt of enslaved Black Haitians against Napoleon and the French. However, unlike the Americans who spoke of the British in terms of “brotherhood,” the Haitians disavowed any kinship with white Europeans.

By distinguishing their Declaration and revolution from that of the United States, the Haitians firmly placed themselves as the model for freedom from colonial rule in the Western Hemisphere. But unlike the United States, which gained recognition and allyship from other nations before winning independence, racism and white fears of future Black independence movements hindered global recognition. The United States did not recognize an independent Haiti until 1862, during the American Civil War, sending its first diplomatic envoy that same year.

“Let us vow to ourselves, to posterity, to the entire universe, to forever renounce France, and to die rather than live under its domination; to fight until our last breath for the independence of our country.”

Haiti Declaration of Independence

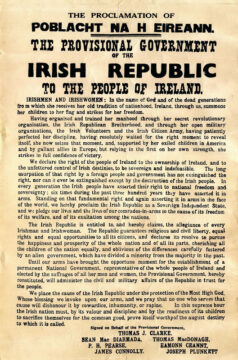

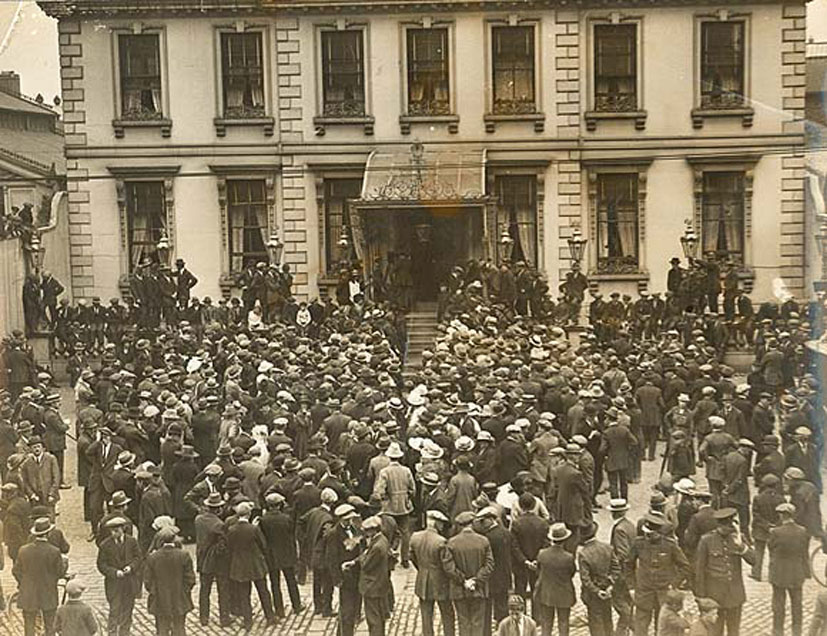

Ireland’s Declaration to be Free From the United Kingdom’s Rule

In 1919, members of the Irish political party Sinn Féin (Ourselves) issued the Proclamation of Independence from the United Kingdom, and a Message to the Free Nations of the World from the Dáil Éireann (Assembly of Ireland), the first independent Irish Parliament since 1800.

Like the Americans’ 1776 Declaration, proponents for a free and independent Ireland argued for their own political independence from the British Parliament and objected to a continued British military occupation.

The signatories to the Irish Proclamation and those serving in the Dáil Éireann understood, as did the Americans in 1776, that global recognition was vital to the new republic’s survival and place in the global community.

No state recognized the independence of Ireland in 1919, though the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 did establish the Republic of Ireland as a dominion, a self-governing country within the British Empire. In 1924, after a civil war in Ireland between competing factions, the United States extended diplomatic recognition to the Republic of Ireland.

“We claim for our national independence the recognition and support of every free nation in the world, and we proclaim that independence to be a condition precedent to international peace hereafter.”

– 1919 Irish Proclamation

Israel’s Declaration of the Establishment of an Jewish Independent Nation State

After the end of WWII and the staggering magnitude of the Holocaust was revealed, the world entered into a new period of multilateral cooperation with the formation of the United Nations in 1945. Sovereign, independent nations comprise the United Nations.

The British had occupied and governed Palestine since 1917 and withdrew in 1948. Arab and Jewish people violently disputed sovereignty of the land, both claiming the territory on the right of historic occupation.

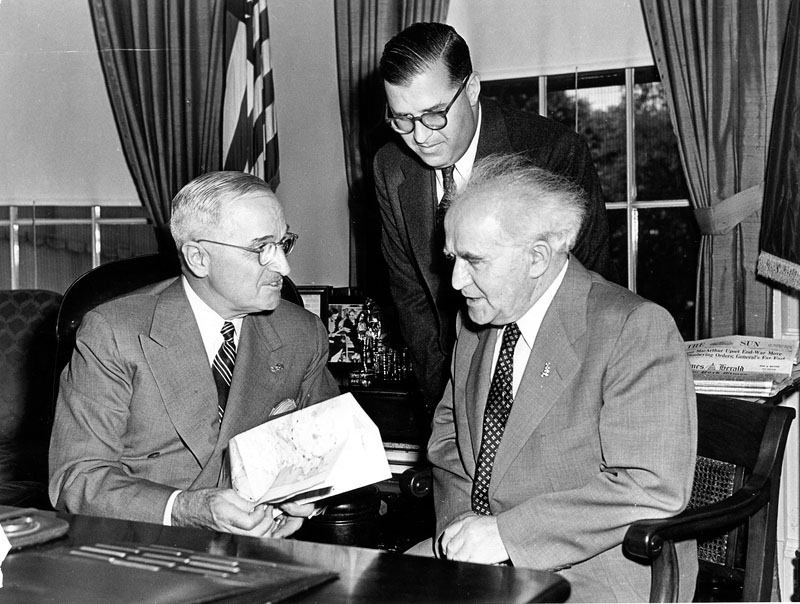

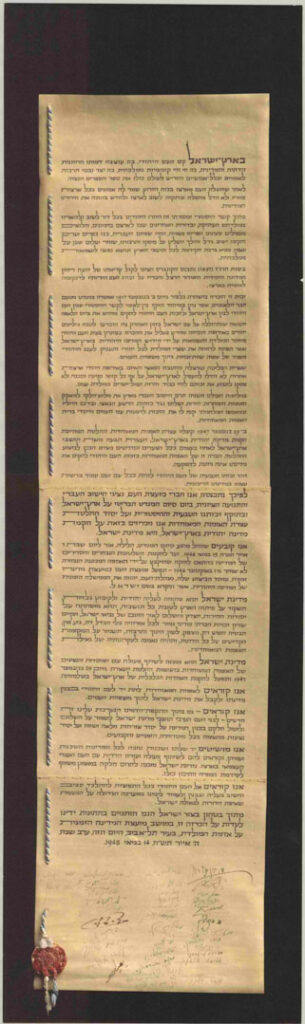

Jewish leaders issued the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, asserting nationhood and appealing (as did the Americans) to the global community (the United Nations) to recognize sovereignty of the first Jewish state.

The United States was the first nation to recognize the Jewish state in 1948 and several nations followed suit, though Israel fought wars with Arab neighbors in the Middle East for several years before attaining recognition from some. Diplomacy was crucial to this process.

“This recognition by the United Nations of the right of the Jewish people to establish their state is irrevocable. This right is the natural right of the Jewish people to be masters of their own sovereign state.”

– Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel

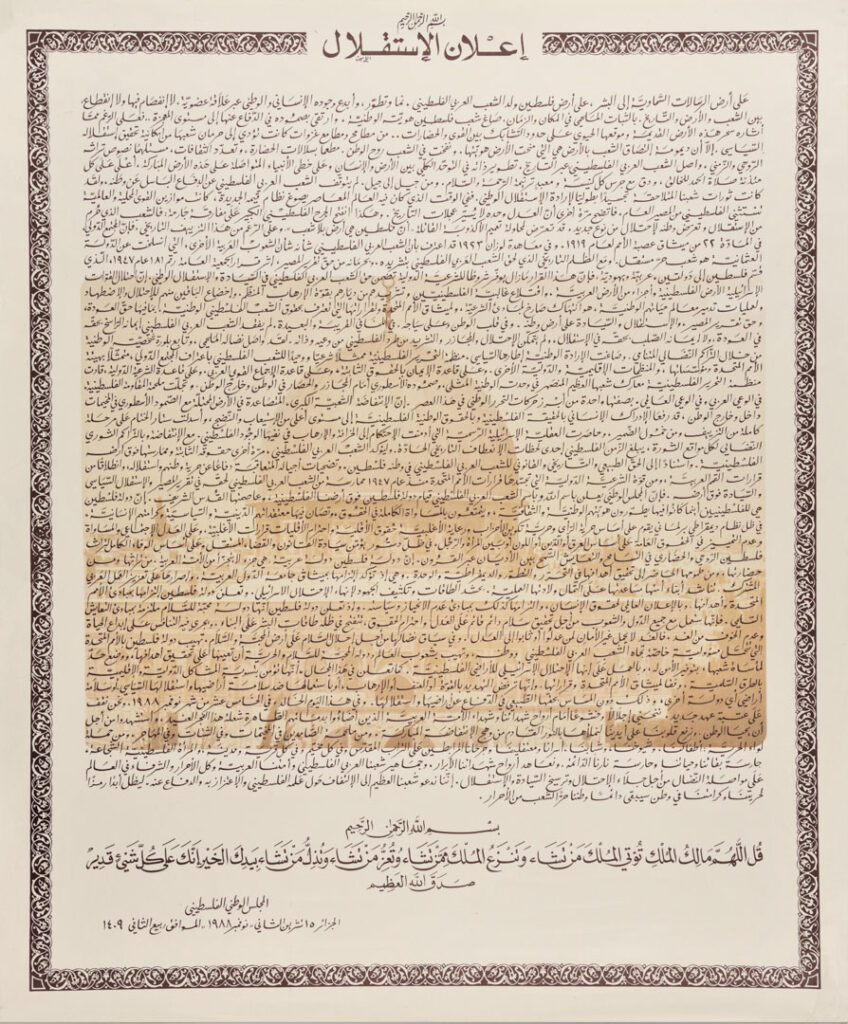

Palestine Declares Its Independence

Diplomats continue to work towards a peaceful resolution between the State of Israel and Arab Palestinian people. In 1988, the Palestinian National Council declared an independent State of Palestine. Similar to the American Declaration of Independence, the Palestinian Declaration argues that people who occupy land forge a national identity, which binds them separately from a ruling power. The Palestinian document also objects to military occupation, a key point of the American Declaration. As of 2012, the United Nations General Assembly considers the Palestinians a non-member observer state.

“With epic tenaciousness in terms of place and time, the people of Palestine fashioned its national identity. Its steadfast endurance in its own defense rose to preternatural levels, for despite the ambitions, covetousness and armed invasions which deprived that people of an opportunity to achieve political independence…”

– Palestine Declaration of Independence

India Asks the United States to Stand By the Values Stated in the Declaration of Independence

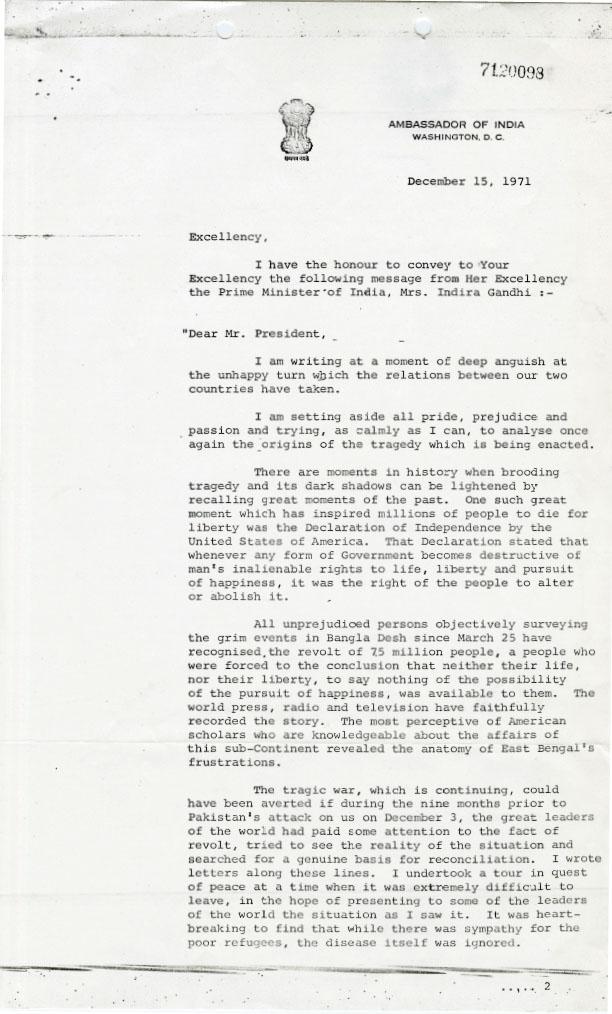

During the 1971 Indo-Pakistani War, Indira Gandhi, the Prime Minister of India, wrote President Nixon a letter imploring him to help protect the democratic rights of Hindu citizens in East Pakistan (now independent Bangladesh). Gandhi cited the Declaration in her appeal for intervention as a similar “moment which has inspired millions of people to die for liberty.”

The Nixon administration wished to keep friendly relations with Pakistan and did not intervene in the crisis. Pakistan had recently helped broker dialogue between the United States and the communist People’s Republic of China, and the U.S. hoped to keep it as a strategic ally during the Cold War.

This view was not shared by many Americans, including State Department employees. Staff at the U.S. consulate in Dhaka (now Bangladesh’s capital) sent a telegram of dissent to State Department leadership stressing that in failing to “denounce the suppression of democracy,” the United States had failed as the “moral leader of the free world.” This telegram shows how in the democratic United States, those serving in the government are free to dissent from official policy decisions without fear of reprisal.

The United States established diplomatic relations with Bangladesh in 1972, but damage was done to the U.S.-India relationship, moving India to seek a strategic relationship with the Soviet Union.

“…that whenever any form of Government becomes destructive of man’s inalienable rights to life, liberty and pursuit of happiness, it was the right of people to alter or abolish it.”

– Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, 1971

Vietnam’s Declaration of Independence

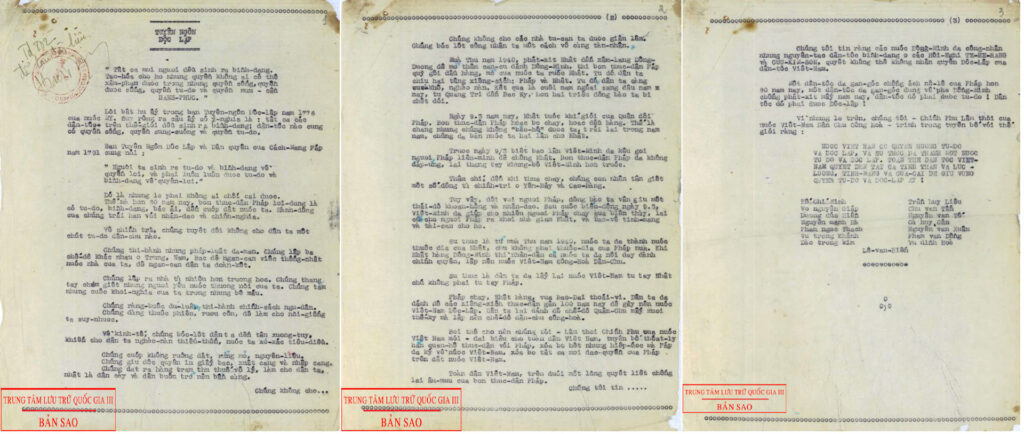

The 1945 Vietnamese Declaration of Independence, part of the post-WWII anti-colonial movement, closely modeled the American Declaration. It quotes exact phrases about human natural rights and lists grievances against the French, who had colonized the territory since the 19th century.

And like the United States, the Vietnamese people would fight long and protracted wars to attain independence. But unlike the United States’ form of government, Vietnam emerged from colonialism as a communist state. To achieve this, Vietnamese revolutionaries fought against the French for its independence from colonization, then it fought the United States for self-determination of government.

“All men are created equal. They are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, among them are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.”

– The Proclamation of Independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, 1945

Sources and Further Reading

David Armitage, The Declaration of Independence: A Global History (Cambridge & London: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

Francis M. Carroll, America and the Making of an Independent Ireland (New York: NYU Press, 2021).

U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian, The Declaration of Independence, 1776

The Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations, Ho Chi Minh and the Vietnam War

U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian, Creation of the State of Israel, 1948