Simulation

Suez Canal Crisis: National Sovereignty versus International Access to Waterways

On July 26, 1956, Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nassar nationalized the Suez Canal, intending to take control of the canal’s operation and its revenue.

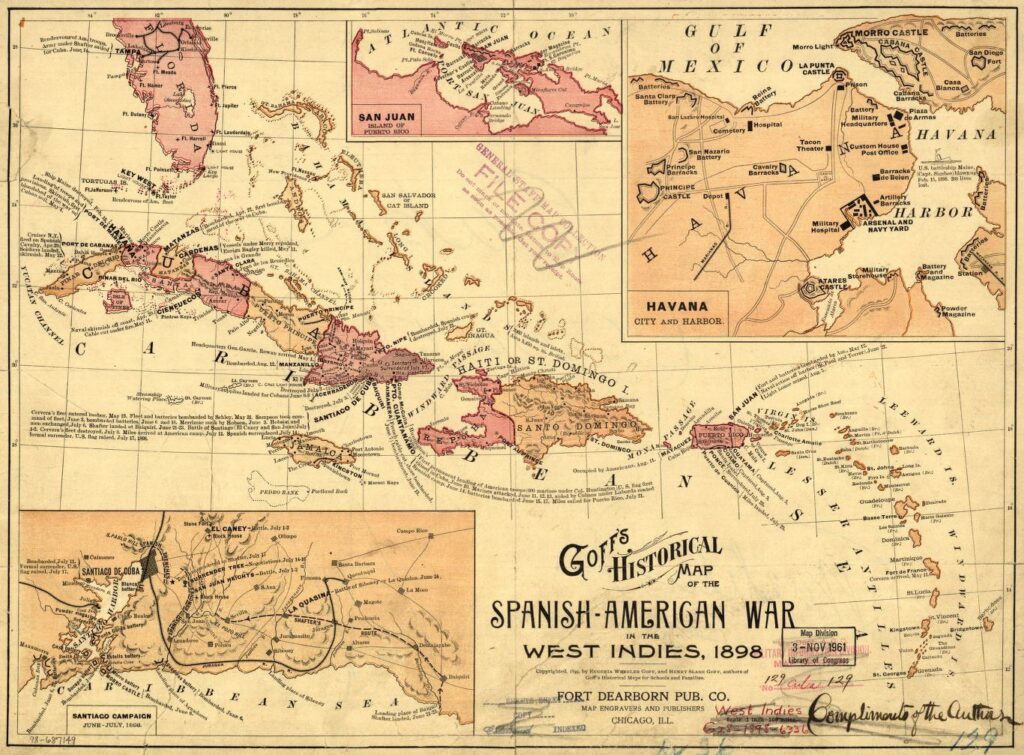

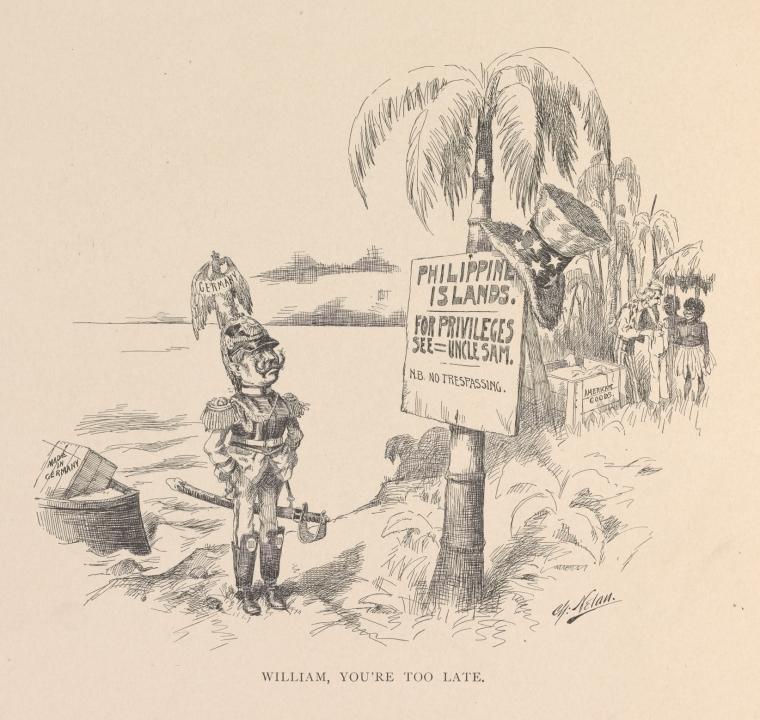

By the 1830s, independence movements reduced Spain’s colonies to Cuba and Puerto Rico in the Caribbean, the Philippines, and several smaller islands in the western Pacific Ocean including Guam, the Marianas, and the Marshall Islands.

At the same time, the United States was increasing its global diplomatic presence and economic power, warning European countries throughout the 19th century from attempting to recolonize countries in the Western Hemisphere.

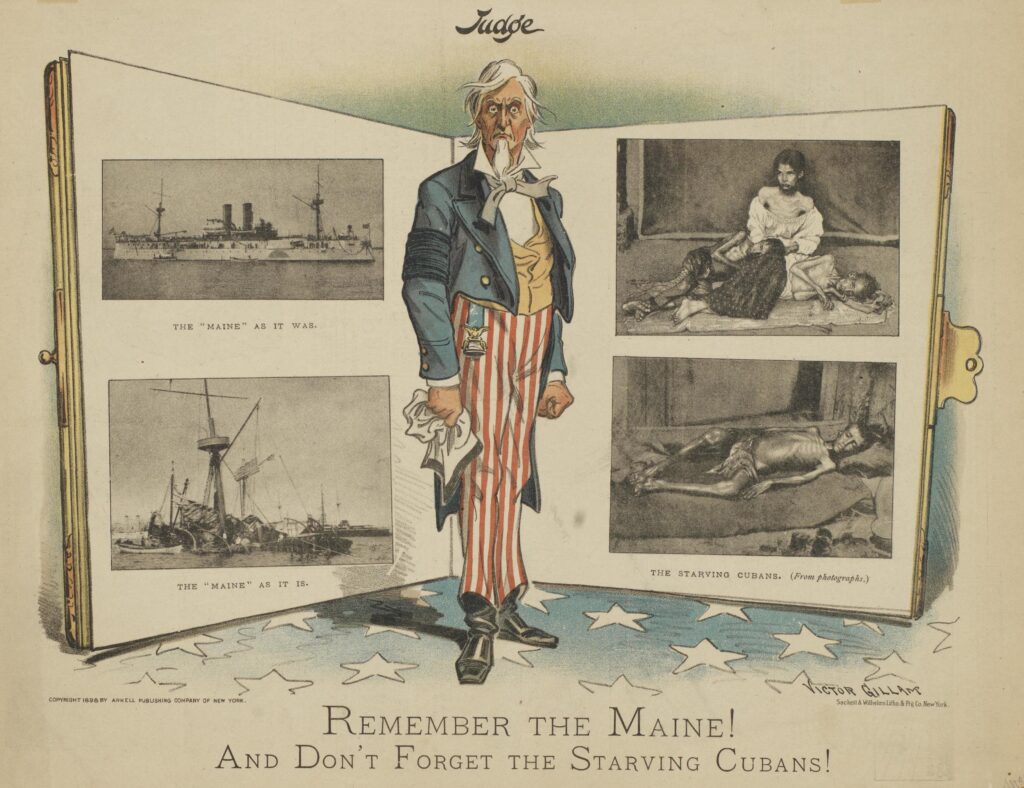

Meanwhile, the American public read newspaper reports of severe Spanish treatment of revolutionaries in Cuba and the Philippines. Many in the United States wanted to go to war against Spain because of these atrocities, and others wanted to use it as an excuse to expand America’s territory. Some wanted to help Cuba become a free and independent country while some wanted the United States to replace Spain and take control over Cuba, as well as the Philippines, to increase its global military and economic power. All could agree that America’s commercial investments in the regions must be protected.

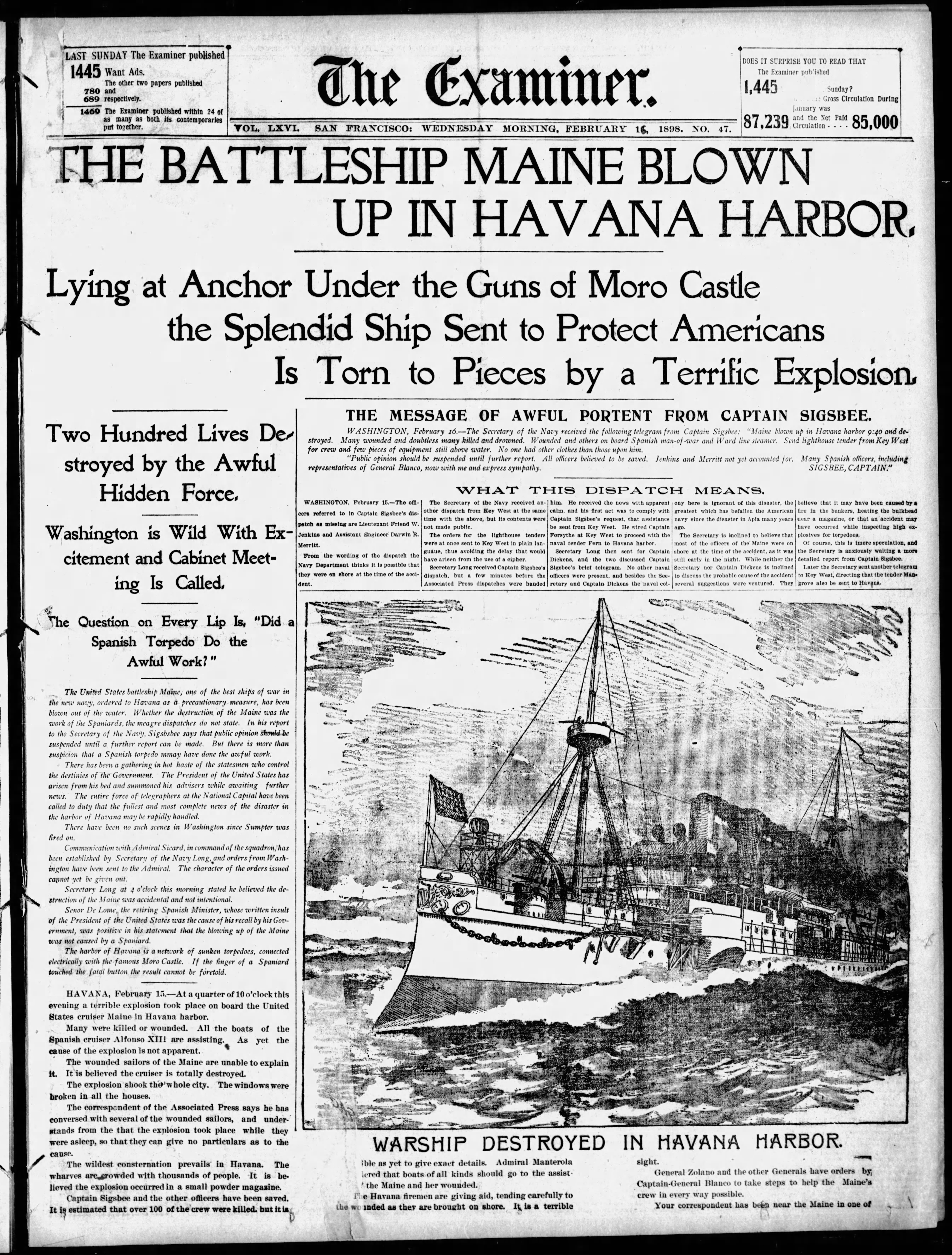

The United States sent the USS Maine battleship to Havana Harbor to protect its citizens and interests in the Spanish-Cuban conflict. On the night of February 15, 1898, an explosion rocked the ship which eventually sank, killing 266 sailors.

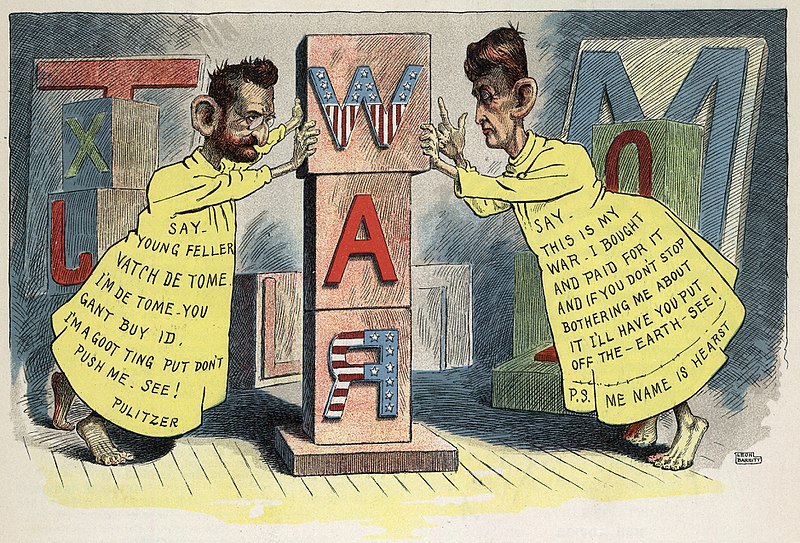

While unclear if this was an attack or accident, the press in the United States blamed Spain immediately, and war between the United States and Spain seemed inevitable.

Could the Spanish keep a stronghold on their last colonies or will the Cuban and Filipino people gain independence?

And would the United States press be able to influence the United States to wage or avoid war?

In the United States after the Civil War, some key foreign policy issues were industrialization, a wave of immigrants, trade, competition with foreign nations, and a naval build-up to protect American global commerce.

After the end of the Civil War in 1865, American manufacturing grew quickly and the foreign policy of the United States responded to this industrial economy. Foreign policy visionaries argued for geographical commercial “spheres of influence” accompanied by strategic naval bases.

As American leaders established firm domestic borders, policymakers followed an aggressive, nationalist foreign policy to achieve these goals. A lasting ideological framework emerged from this time period: military strength and economic prosperity solidified national security.

Three Secretaries of State in President William McKinley’s administration shaped foreign policy in the late 19th century: John Sherman, William Day, and John Hay.

John Sherman was appointed Secretary in 1897. Both Sherman and McKinley preferred diplomatic engagement rather than military intervention in Cuba. However, Sherman and McKinley’s other foreign policy views frequently diverged and tensions between the two ran high. When it became clear that Spain would not concede and grant Cuban independence, the USS Maine was sent to Havana as a warning.

Sherman resigned shortly after the USS Maine exploded, and McKinley appointed William Day, the Assistant Secretary of State under Sherman, to replace him just after the United States declared war on Spain in April 1898. Spain was defeated in four months. Day led a commission to begin treaty negotiations with the Spanish delegation but resigned before its conclusion. Secretary John Hay succeeded him, finalizing the terms of the 1899 Treaty of Paris.

The State Department during this period was also defined by the economic and geographical expansion of the United States. American diplomats, who were not yet the professional Foreign Service as we know it today, worked in missions and consulates around the world to support expansionist policies.

In the United States, foreign policymakers searched for foreign markets to keep American manufacturing prices competitive, as production was far greater than the population of the United States could consume.

Under President McKinley, Secretary of State Hay conceived of the “Open Door Policy,” a trade policy designed to sell American goods to Chinese customers. Hay hoped this policy would expand throughout Asia, as the United States had aggressively overthrown the Hawaiian monarchy and annexed the islands to establish a naval base to protect its Pacific commerce. Similar trade policies followed in the Caribbean, Central, and South America, some mutually favorable and others aggressively favoring the United States at the expense of other nations.

Please find below a playlist of short videos from experts in the field to aid discussion and exploration of the topic.