Diplomacy through Many Storms: Ambassador Lino Gutiérrez

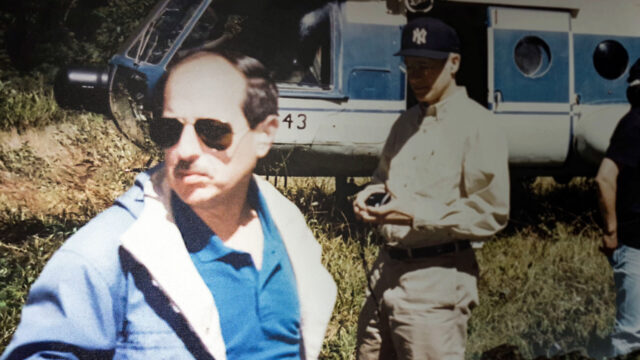

When Lino Gutiérrez joined the U.S. Foreign Service in 1977, he found himself to be the only Latino in his class. At that time, Hispanic Americans comprised only four percent of the diplomatic corps. During his 30 years in the U.S. Foreign Service, Gutiérrez served in the Caribbean, Europe, Latin America, and Washington, D.C., including ambassadorships to Nicaragua and Argentina.

As a native Cuban, Gutiérrez experienced a storm of political upheaval before coming to the United States. His upbringing fostered a deep interest in international relations. It also taught him the importance of remaining calm and composed during turbulent times.

Gutiérrez honed these skills during his diplomatic career through political unrest, weather catastrophes, and national tragedies.

Gutiérrez’s Childhood in 1950s Cuba

Lino Gutiérrez was born in Havana, Cuba in 1951. Lino’s father, also named Lino, was a Professor of Mathematics at the University of Havana. His mother, Maria, was a teacher.

His parents firmly opposed Cuban President Fulgencio Batista’s brutal regime after Batista, supported by a U.S.-backed illegal coup, seized power in 1952. Gutiérrez’s father was part of the civil resistance that covertly provided food and medicine to rebels fighting against Batista. While growing up, Lino recognized the danger of opposing the government. He recalls his mother admonishing him to be cautious and not to badmouth Batista in public.

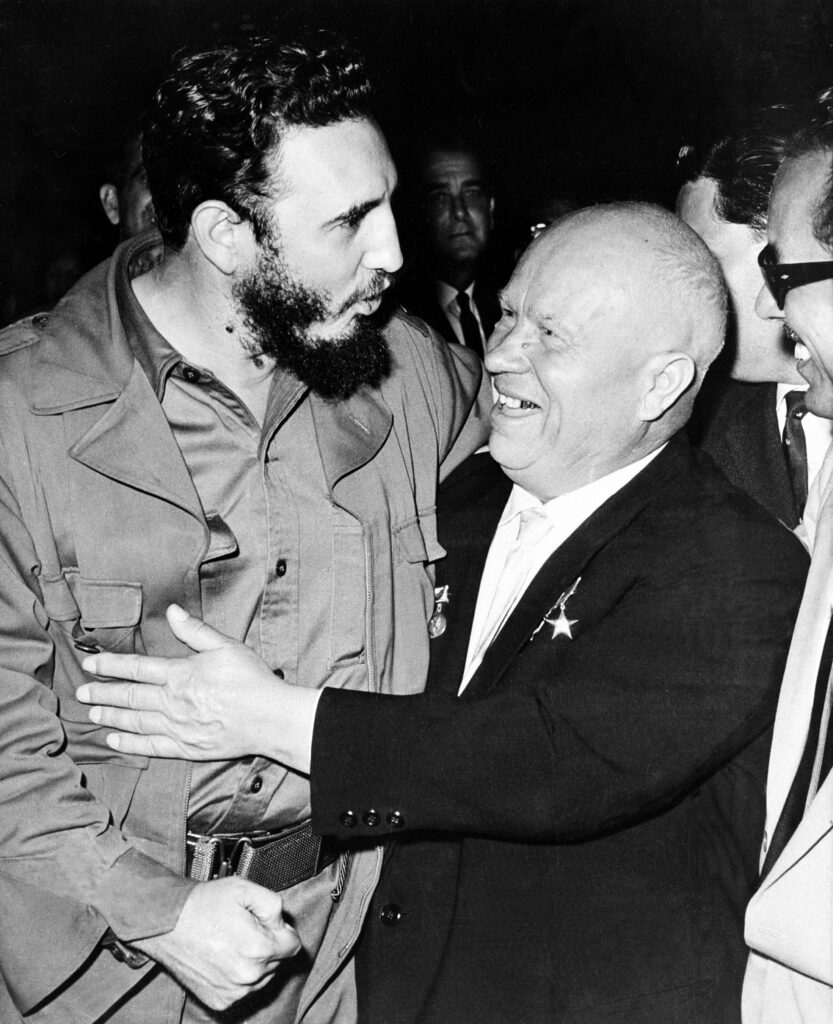

By 1958, most Cubans stood against Batista. After the United States refused to support Batista’s government, Batista fled the country, and the socialist revolutionaries took control. “It was a great moment,” Gutiérrez said, “the dictator has fled, and a new era of peace and democracy was sure to follow.”

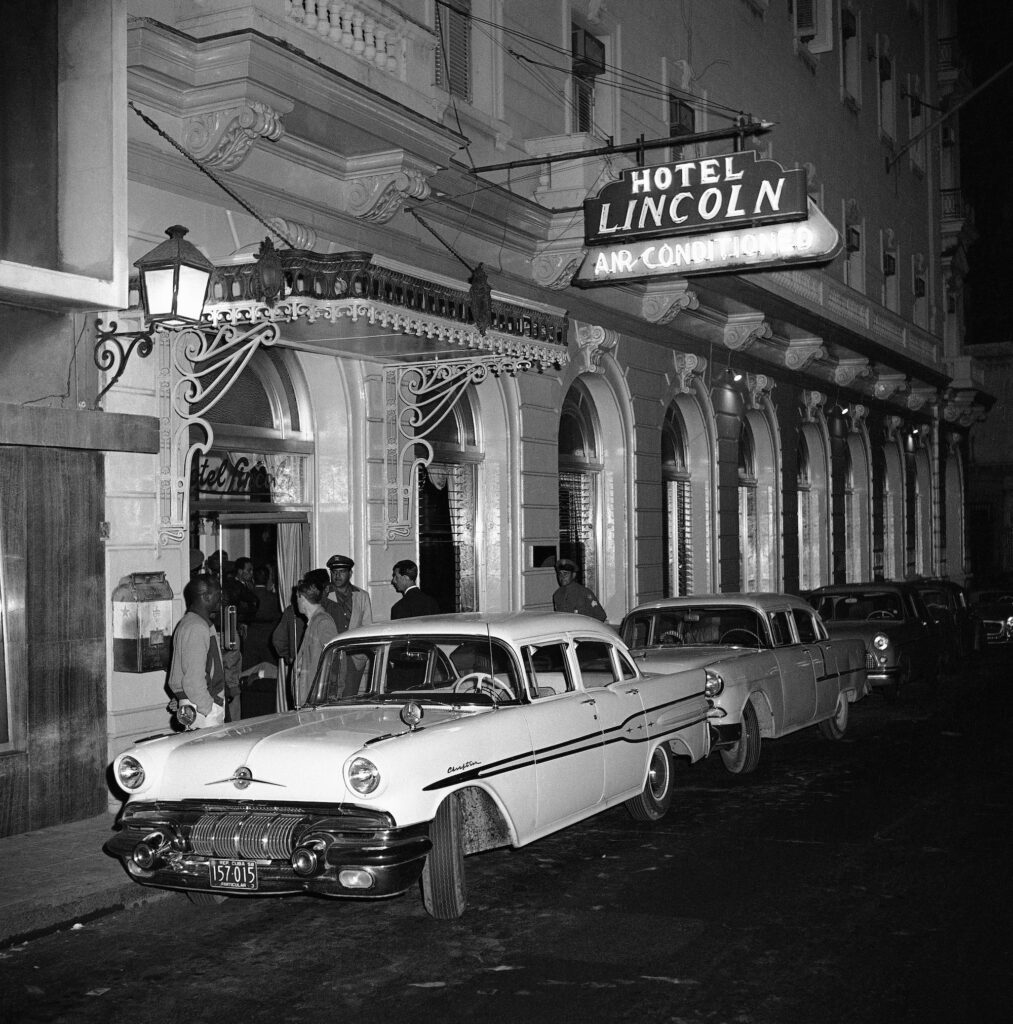

This hope soon faded, as revolutionary Fidel Castro became Prime Minister in 1959 and many Batista loyalists were executed by firing squad after sham public trials. U.S.-Cuban relations deteriorated further when Castro reached out to the Soviet Union. Life in Havana radically changed as Soviet propaganda replaced American cultural icons.

Escaping Cuba

Gutiérrez’s parents decided they could not remain in Cuba under this radical political shift. In June 1961, two months after the failed Bay of Pigs invasion, Professor Gutiérrez calmly started to prepare for the family’s escape.

Gutiérrez’s father received the government’s permission for his wife and son to “visit” her sister in Cali, Colombia. It was “a vacation,” Lino said, “from which we never returned.”

Six months later, Professor Gutiérrez went to a math convention and defected, joining the family in Colombia.

Moving to the Segregated American South

In 1962, Gutiérrez’s father received an offer to teach at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa during the height of racial segregation and civil protest.

Gutiérrez’s family had the eye-opening experience of seeing water fountains marked “colored.” He remembers when Alabama’s racist segregationist Governor George Wallace stood in the doorway at the University of Alabama to prevent the enrollment of two African American students. The family thought, “We have gone from Castro to Wallace! What’s next?”

Despite living and working in the volatile midst of the transition to racial integration, the family was relieved to be in the United States “to make a living and survive and get ahead,” said Gutiérrez. Gutiérrez himself attended the University of Alabama and earned a degree in Political Science in 1972. After teaching in Miami for two years, Gutiérrez returned to the University of Alabama and graduated with an MA in Latin American Studies.

Joining the Foreign Service

Having a keen interest in international relations, Gutiérrez entered the Foreign Service in 1977. His first assignment was to the Dominican Republic, despite his request for a posting to Naples, Italy. Being one of the few Latino Foreign Service Officers, he did not want to be “typecast” as an officer sent only to non-European Spanish-speaking nations.

He attributes this first posting to both his bilingualism and his graduate studies. When he asked his career counselor about it, the counselor said, “We thought that if you didn’t want to go to Latin America, why did you major in Latin American Studies?” Lesson learned, Gutiérrez later said: “You are your own advocate.”

Gutiérrez’s composure, coupled with his academic and diplomatic expertise in Latin America, proved invaluable. In the 1980s, during the Cold War, U.S. foreign policy began to focus intensely on political unrest and the fears of the spread of communism in Latin and South America.

The 1983 Invasion of Grenada

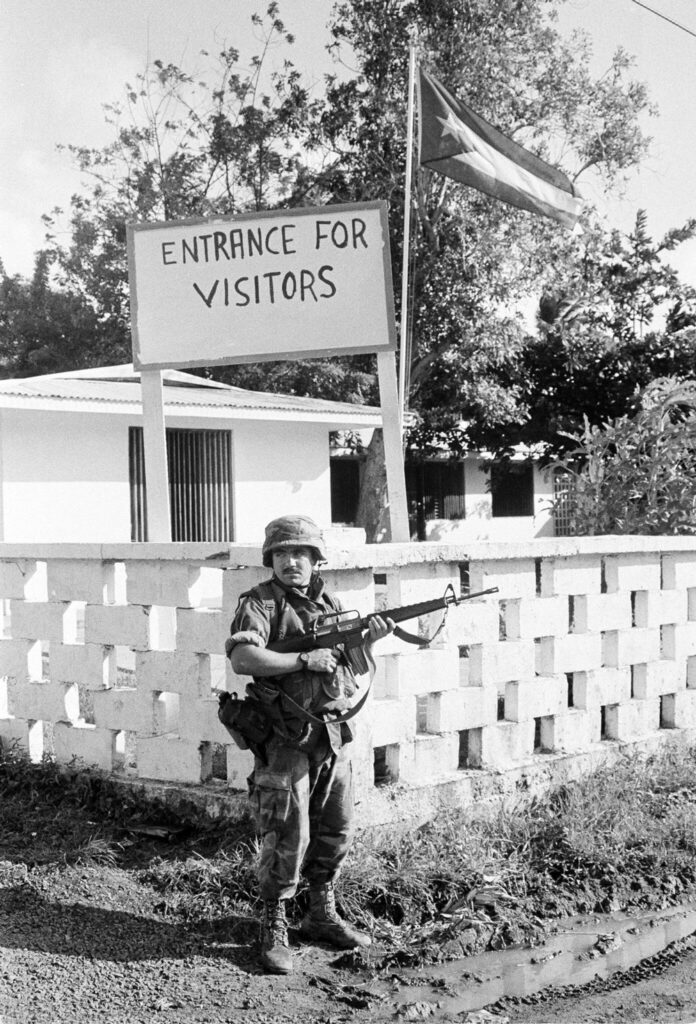

In October 1983, while serving as head of the Political Section in Haiti, a U.S.-led coalition invaded Grenada, a small communist Caribbean island. President Ronald Reagan justified the military invasion by pointing to an increase in Soviet-Cuban militarization on the island. The U.S. government suspected that Cuba and the Soviet Union intended to use the island as an airbase to launch attacks against the United States.

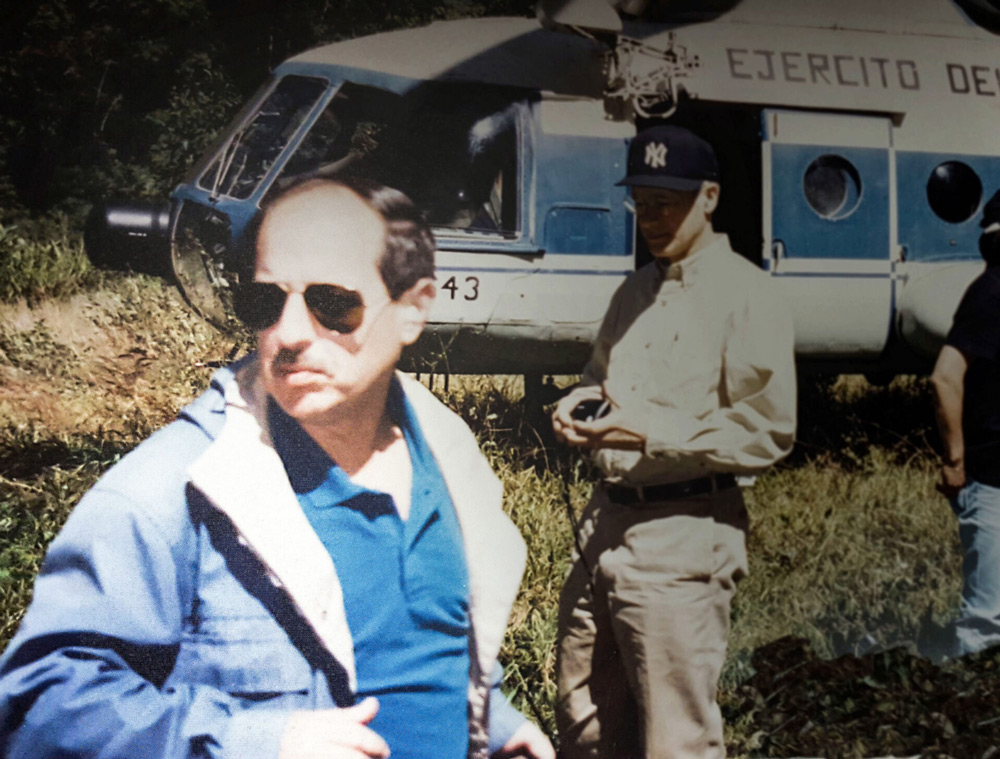

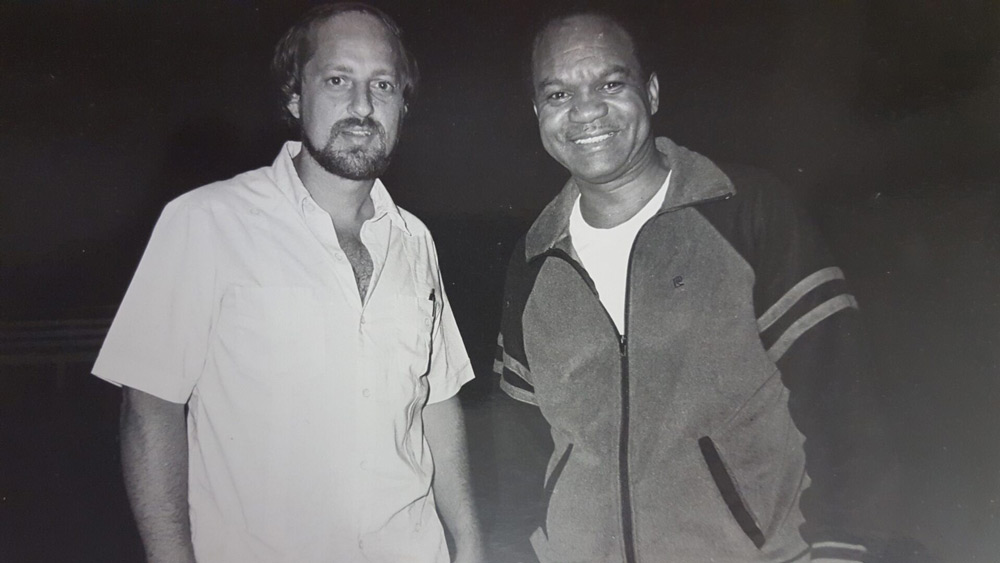

About a week after the invasion, Gutiérrez arrived in Grenada on a temporary tour of duty to negotiate the evacuation of the island’s Cuban diplomats.

When Gutiérrez arrived, the fighting had largely ended, but the situation on the ground remained tense. Cuban nationals were anxious to get home.

Gutiérrez arrived at the Cuban embassy and informed the Cuban ambassador to Grenada that the United States had offered to evacuate all Cuban diplomats and their belongings. The ambassador agreed.

However, when Gutiérrez arrived with a military caravan to pick up the Cuban diplomats, the Cuban ambassador told him they would not permit a search of personal belongings.

Calmly, and knowing the United States had the upper hand, Gutiérrez explained that the U.S. Air Force required the search for the safety of the aircraft and crew. The Cuban ambassador refused to comply. Calling his bluff, Gutiérrez responded, “Fine, if that’s your position,” and left with the trucks.

Within a day, the Cuban ambassador agreed and the diplomats were successfully evacuated, demonstrating that cooler heads had prevailed.

Evacuating Americans from the Bahamas during Hurricane Andrew

As the Deputy Chief of Mission (DCM) in the Bahamas in 1992, Gutiérrez faced a literal storm—Hurricane Andrew.

With 160+ mph winds barreling towards the islands, Gutiérrez not only had to contend with the safety of embassy personnel but also for the safety of hundreds of tourists. In situations like this, Gutiérrez explained, the United States government held no double standard in giving diplomats an unfair advantage over the general American tourist population.

Previous hurricane evacuations complicated the evacuation of 1992. In recent years, the State Department spent considerable money on unnecessary last-minute evacuations. As a result, Gutiérrez said, “My instructions were clear: don’t ask for the evacuation of personnel because the Department will not agree to do so.”

However, Gutiérrez pressed to evacuate non-essential personnel. By the time the request was granted, it was too late to escape the Category 4 storm.

Gutiérrez, his family (including their cat), and about 50 other embassy personnel rode out the storm in the concrete embassy building. When Gutiérrez flew over the islands with the Bahamian Prime Minister to inspect the damage, the total came to $250 million.

Observing the Composure of Secretary Powell during 9/11

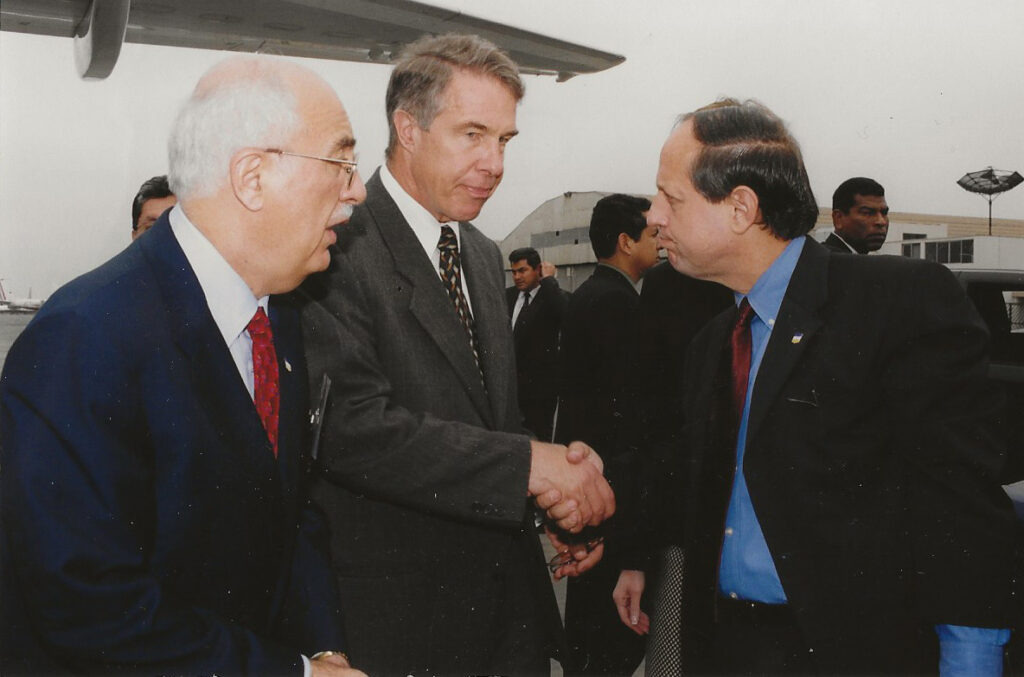

On September 11, 2001, as Acting Assistant Secretary of State for the Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs, Ambassador Gutiérrez was in Lima, Peru with Secretary of State Colin Powell. They were there for a special meeting of the Organization of American States (OAS) General Assembly, where Secretary Powell was appealing for all member states to sign the Inter-American Democratic Charter.

Before the meeting, Powell and Gutiérrez were having breakfast with Peru’s President, Alejandro Toledo. An aide handed Powell a note informing him a plane had hit one of the World Trade Center towers.

A few minutes later, the aide gave Powell another note. Powell told the group a second plane had hit the other tower and instructed the aide, “Get the plane ready; we’re going back.” But since it would take an hour to get the plane ready, Powell decided the Americans would go to the OAS meeting. On the way to the meeting, they learned of the attack on the Pentagon.

Under these stressful and uncertain conditions, Secretary Powell remained composed and asked to address the assembly, to let them know what was happening. Ambassador Gutiérrez remembers it as one of the “finest speeches [he] has ever heard,” and the members gave a standing ovation. “It was a great moment of solidarity with the United States,” he recalls.

Powell apologized for having to leave the meeting early but asked the members to consent to the Inter-American Democratic Charter so he could sign it before departing. The members agreed and then began giving long speeches asserting their support for the United States.

Concerned about his family in the D.C. area and the nation, Ambassador Gutiérrez understood he needed to help move the proceedings forward. The Honduran Foreign Minister was giving the last speech. Secretary Powell turned to Gutiérrez and said they needed to leave right away. Calmly, Gutiérrez wrote in Spanish on a piece of paper, “Secretary Powell has to leave NOW,” and slipped it to the Honduran delegation. Message received, and the assembly approved the Charter.

A Role Model for the U.S. Foreign Service

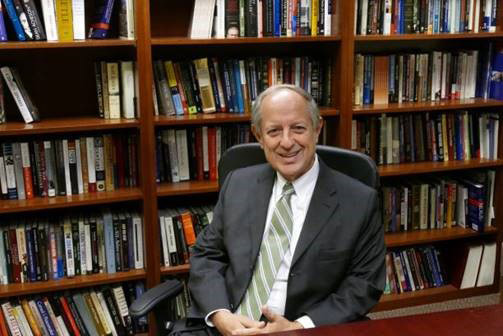

Gutiérrez’s last assignment was Ambassador to Argentina (2003) before his retirement in 2006. He leaves an impressive legacy and serves as a role model for many. He assisted in creating the Hispanic Employee Council of Foreign Affairs Agencies (HECFAA), which remains an active U.S. Department of State employee affinity group with a robust membership.

His work in diplomacy continues. Ambassador Gutiérrez currently serves as Executive Director of the Una Chapman Cox Foundation. Along with supporting the work of the foreign service through fellowships, education programs, and academics, the foundation participates in diversity and inclusion initiatives to reach underserved and underrepresented communities.

Sources Consulted

- ADST Oral History of Ambassador Lino Gutiérrez (July 2007)

- HECFAA 2021 Oral History Interview

- “Where We Stand: The Foreign Service by the Numbers,” AFSA