Boa Lee: Diplomacy Can Overcome Tragedy

In 2012, I had just arrived at my first overseas assignment in Sierra Leone when I was asked to deal with a protest outside the U.S. embassy. Relatives of people killed during Sierra Leone’s decade-long civil war wanted to speak to the U.S. ambassador about the death of their loved ones.

Seeking justice and dealing with post-war trauma were two things I, a former community organizer and the child of Laotian Secret War refugees, knew well. Recognizing the protestors’ main goal was for American officials to listen to their concerns, I escorted a handful of its representatives to meet with then-U.S. Ambassador to Sierra Leone, Michael Owen.

It was my experiences as a community organizer and a child of refugees that led me to pursue a career at the U.S. Department of State. As a foreign service officer, I have the privilege of using my skills in advocacy, communication, and collaboration to help people around the world.

Boa Lee: The Child of “Free” People

My parents were part of the Hmong population in Laos, who referred to themselves as the “free people.” During the Secret War in Laos, they and many others fled to Thailand as refugees.

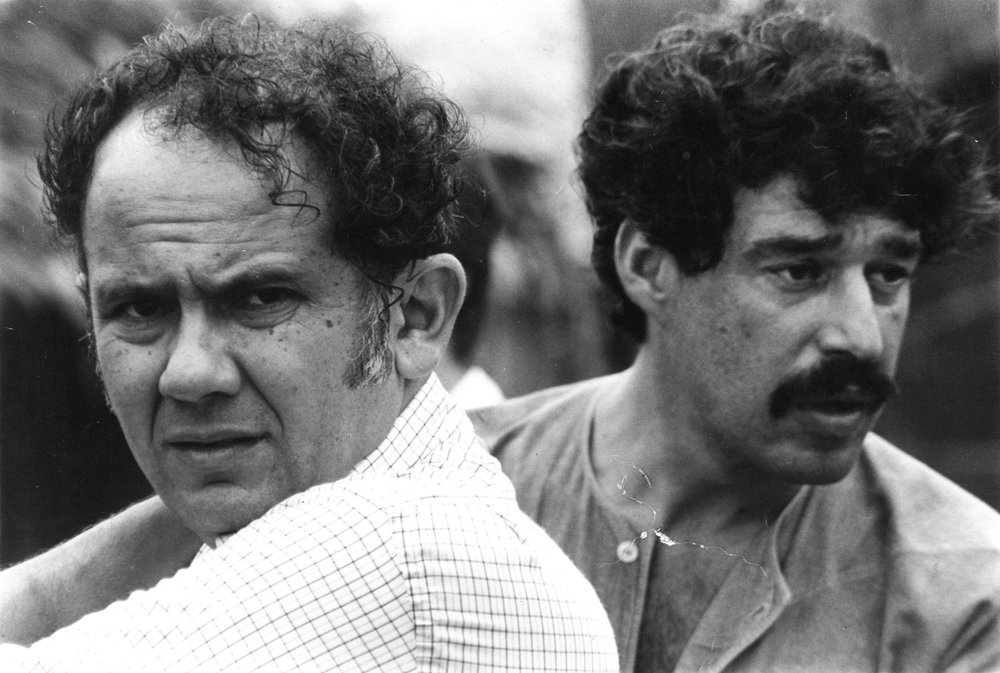

Lionel Rosenblatt, the refugee coordinator at U.S. Embassy Bangkok in 1979, was among the first U.S. officials to meet with Hmong leaders.

Rosenblatt and his team successfully convinced a reluctant U.S. Congress to accept Hmong refugees for resettlement in the United States. This was not an easy task as the Hmong were considered by many U.S. leaders at the time as illiterate farmers.

Thanks to the dedication of Rosenblatt and colleagues in helping the Hmong people, my parents arrived in the United States in 1979. As of 2021, there are nearly 300,000 Hmong in the United States.

Thirty-five years after the arrival of the first Hmong refugees to the United States, I am proud to have become the United States’ first Hmong-American Foreign Service Officer.

What was the Secret War in Laos?

What was the Secret War in Laos?

In the 1960s, a covert operation by the CIA recruited and trained the Hmong and other ethnic hill tribes in Laos to fight communist forces in what has been called the Secret War in Laos.

The war was “secret” because the American people were unaware of the operation, which continued despite the United States signing an agreement in 1973 to leave Laos. The Hmong – referring to themselves as “free people” – supported the United States. They rescued downed American airmen and defended against the military advance of communist soldiers for more than ten years.

When the Secret Wars ended in 1975, an estimated 40,000 Hmong soldiers had been killed, and 3,000 were missing in action – exceeding U.S. losses on a per capita basis. Thousands of Hmong were displaced and fled Laos across the Mekong River, ending up in refugee camps in Thailand.

Boa Lee: Defender of Peace and Justice

I remember growing up hearing stories about my family’s hardships in Laos and Thailand. Communist soldiers shot my aunt in the back, killing her while she was carrying her baby. My maternal grandfather died serving in the Hmong Secret War army and his remains are still unfound. In my father’s escape from Laos, he paid Laotian and Thai people to sneak him across the Mekong River. My parents ended up in the Ban Vinai refugee camp, where they met and married.

I was born in Pennsylvania, and in the 1980s my parents, Bee Lee, a janitor, and Mee Yang, a homemaker, moved to Saint Paul, Minnesota. That is where they raised six children in a public housing project.

The poverty and violence I saw growing up in my low-income neighborhood in Minnesota motivated me to go to college. I studied journalism and sociology, hoping to tell the stories of the city’s growing number of immigrants.

After college, I worked for nearly ten years as a community organizer in Frogtown, one of the poorest neighborhoods in St. Paul. It was in Frogtown where I honed my skills working across diverse groups for social and racial justice. I organized campaigns to seek justice for victims of police brutality, advocated for more equitable use of public financing to help communities of color, and fight hate speech on the airwaves.

By the time I entered the U.S. foreign service in 2012, I had gained confidence in my leadership skills and learned the value of hard work. It was important for me to become a diplomat because I had seen the devastation of war and conflict, and understood the powerful role of peaceful dialogue.

Developing a More Diverse U.S. Foreign Service

Throughout my foreign service career, it has been important to me to support increasing diversity at the U.S. Department of State. I was honored to be twice elected to serve on the board of the Asian American Foreign Affairs Association (AAFAA), one of the State Department’s employee affinity groups.

While serving on the AAFAA Board, my colleagues and I worked with the American Foreign Service Association in 2019 to award the first financial stipend to Department of State interns from historically underrepresented Asian American Pacific Islanders (AAPI) communities in the United States.

I believe we cannot be complacent when it comes to seeing the problem of lack of diversity. We must be compassionate in hearing the stories and needs of colleagues of color. And we should not be complicit in continuing to deny Americans the value of a diplomatic corps that looks like all of the United States.

“We are a stronger and more effective U.S. Department of State when we can bring our unique backgrounds and experiences to bear to help the American people and our allies. Even the child of refugees can become a U.S. diplomat one day.”

– Boa Lee