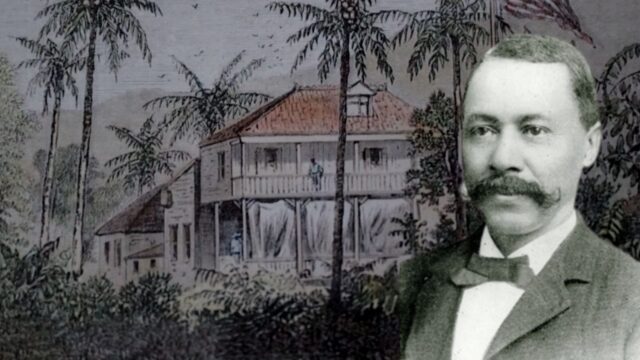

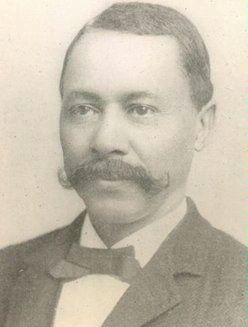

Ebenezer D. Bassett: America’s First African American Chief of Mission

In 1869, Ebenezer D. Bassett was appointed as the U.S. Minister to the Republic of Haiti, making him the first African American Chief of Mission. Throughout his career, Bassett defended the civil rights of African Americans and black Caribbean nations.

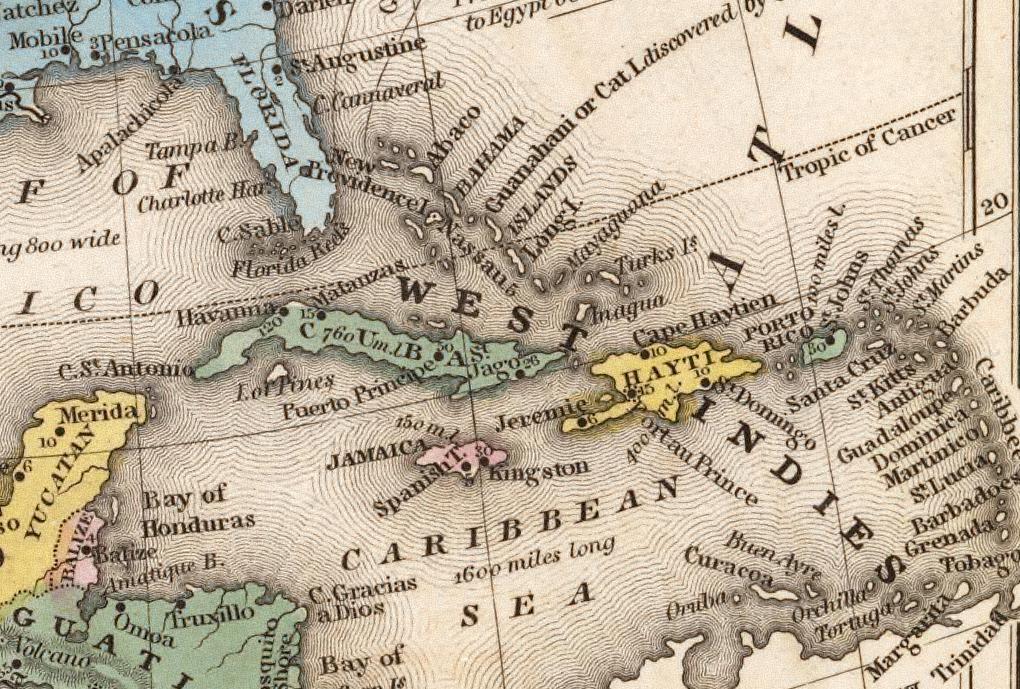

1862: Formal Recognition of the Republic of Haiti

The Civil War (1861-1865), a conflict fought to determine the future of the American Republic, also forever changed the meaning of the long-cherished American values of freedom and liberty. By Executive Order 95 of 1862, the “Emancipation Proclamation,” President Abraham Lincoln declared that as of January 1, 1863, all slaves in the self-proclaimed Confederate States of America, were “forever free,” a promise kept at war’s end.

The year 1862 also marked a turning point in American diplomatic history, as Lincoln became the first U.S. President to formally recognize the Republic of Haiti.

Established in 1804, Haiti was the first “Black Republic” in the Western Hemisphere and the first successful slave revolt against white European colonizers. The United States–a slaveholding republic–refused to recognize Haiti, fearing the contagion of slave rebellions, but Americans nonetheless engaged in the robust sugar cane and coffee trade with the small island nation.

With the Emancipation Proclamation, formal recognition of Haiti, and the establishment of diplomatic relations, the United States took an enormous step in redefining principles of liberty and democracy both at home as well as abroad.

Ebenezer D. Bassett: The First African American Chief of Mission

Shortly after the conclusion of the war and the reunification of the United States, American legislators codified African American liberties, citizenship, and universal male voting rights under the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution.

It was a period of time when African American men began to hold elected offices in local, state, and federal government, including presidential appointments under Ulysses S. Grant.

While Lincoln had appointed a white man to be first Minister to Haiti, Benjamin Whidden, President Grant selected a Philadelphia school principal for the post, Ebenezer D. Bassett. He would become America’s first African American Chief of Mission and a champion for international human rights.

Representing the United States in Haiti

Freeborn and a native of Connecticut, Bassett was a college graduate and a friend of Frederick Douglass–who had warmly recommended him to the President. Bassett had proactively written Grant to request the appointment noting that black Americans had faith the President would continue to advance full equality.

“My appointment,” he wrote, “would be hailed by them, especially by recently enfranchised colored citizens, as marked recognition of our new condition in the Republic and an auspicious token of our great future.“

– Ebenezer Bassett

After his appointment in 1869, then 36-year-old Bassett arrived in Haiti with his wife and four young children just as that country was torn by its own civil war. The Haitian President, Sylvain Salnave had seized power in a bloody coup two years before and now struggled to keep it. The outgoing American Minister, Gideon Hollister, warned Bassett of the unrestrained violence, even against diplomats. A workman had attacked Hollister in his own home with a hatchet, leaving the diplomat with severe scalp wounds.

A Champion of Human Rights

When Bassett presented his credentials to President Salnave, the American made clear he was there to ensure that “all class of men under the broad shield of [his] government stand equal before the law,” a tacit reminder he meant to uphold the rule of law.

For Bassett, however, rule of law principles extended beyond the written law into morally held beliefs grounded in humanitarian and religious virtue.

His deeply held belief was soon tested, as some terrified 3,000 refugee men, women, and children from the wartorn capital flooded his 15-acre compound seeking protection as Salnave’s government began to crumble. The U.S. Secretary of State, Hamilton Fish, had warned Bassett to remain neutral in the political fight and to inform the refugees “that your government cannot…assume any responsibility for them.”

Without any direction from Washington, Bassett quickly negotiated with the new rebel government to ensure safe passage of the refugees to their homes, politely and courageously telling the new president, Jean-Nicolas Nissage Saget “that the holding of women and children as hostages is repugnant to modern civilization and especially to the government of the United States.” Bassett personally escorted the refugees into Port-au-Prince and ensured their safety, as his suspicions of Saget proved correct when he learned several Haitians deemed political opponents had been found with their throats slit, without due process of trial.

Protecting Refugees’ Right to Asylum

Throughout the years Bassett served as Minister his commitment to humanitarian principles often placed him in conflict with Fish, who consistently refused to recognize an individual’s right to asylum under the protection of the United States.

In May 1875, a new Haitian President, Michel Domingue, began a military crackdown on civilians and officials he believed were stirring up opposition to his authority. From his home, Bassett watched in horror as fighting again broke out and soldiers indiscriminately shot civilians in the streets–including children. He also learned that Domingue’s militia had killed two generals as they futilely barricaded themselves in their homes.

It was no surprise then when shortly afterward former General Pierre Boisrond Canal and his brother arrived at Bassett’s home pleading for protection. Bassett immediately took the men in and wrote a twenty-one-page dispatch to Fish, explaining in great detail the situation on the ground and why he had taken the action he did. Fish angrily responded, “It is regretted that you deemed yourself justified by an impulse of humanity to grant such an asylum. You have repeatedly been instructed that such a practice has no basis in public law and so far as this government is concerned is believed to be contrary to all sound policy.”

For five months, Bassett held firm against the pressures from Washington and the Haitian government, refusing to expel Boisrond Canal from his home. He explained to Fish that his conscience would not allow it.

“To have closed my door upon the men pursued would have been for me to deny them their last chance of escape from being brutally put to death before my eyes.”

– Ebenezer Bassett

Eventually, Domingue relented under Bassett’s persistent negotiations, agreeing to commute Boisrond Canal’s death sentence to banishment, and allowing the American diplomat to safely escort Boisrond Canal to a U.S. ship destined for Jamaica.

“Refugees amicably embarked and soldiers withdrawn from around my home,” Bassett informed Fish in plain terms. Cooly, with no congratulatory language on the peaceful resolution to the ordeal, Fish informed Bassett that he did not believe the American minister had deliberately violated the law.

A Legacy of Humanitarianism

Bassett served his post as Minister to Haiti honorably for eight years, submitting his resignation at the end of Grant’s presidency which was accepted by the incoming Rutherford B. Hayes administration.

He returned with his family to his hometown in Connecticut and Yale University invited him to speak, where he delivered a speech titled “The Right of Asylum.”

For the remainder of his life, Bassett continued to practice diplomacy and espoused the humanitarian causes he had so ardently defended as Minister. He served as the Consul General for Haiti in New York City and as official secretary to Frederick Douglass when President Benjamin Harrison appointed the venerable abolitionist and statesman to be Minister of Haiti in 1889.

Until his death in 1908, Bassett remained steadfastly committed to the civil rights of African Americans and continued to defend the rights of the black Caribbean nations.

Sources Consulted:

Christopher Teal, Hero of Hispaniola: America’s First Black Diplomat, Ebenezer D. Bassett (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2008)

Heinl, Nancy Gordon, “America’s First Black Diplomat,” Foreign Service Journal (August, 1973), 20-22.

Douglass, Frederick, “Haiti and the United States. Inside History of the Negotiations for the Mole St. Nicolas,” The North American Review, Vol. 153, No. 418 (Sept., 1891), 337-345.

Sears, Louis Martin, “Frederick Douglass and the Mission to Haiti, 1889-1891,” The Hispanic Historical Review, Vol. 21, No. 2 (May, 1941), 222-236.