From Secretaries to Senators: The Historic Road to the Presidency

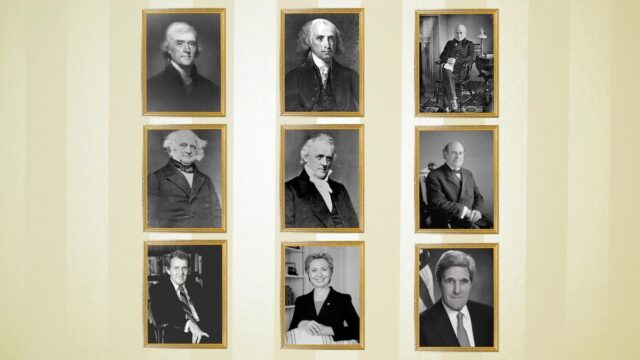

In the early years of the Republic, the Secretary of State cabinet position appeared to be a stepping stone to the presidency. This pattern began with Thomas Jefferson, who became the first Secretary of State and then the third President of the United States.

However, in the 1830s, Secretaries of State became markedly less successful in their presidential runs. The relationship between the Department of State, the Congress, and the Presidency sheds light on a long relationship between politics and diplomacy.

1800: Secretary Jefferson becomes President

There have been 16 Secretaries of State who have run for president. Also, 25 former Secretaries of State have served in the U.S. Senate, many on a foreign relations committee.

The first Secretary of State of the United States was Thomas Jefferson, serving from March 22, 1790, to December 31, 1793. Jefferson also became the first of 6 Secretaries of State to become President of the United States, serving as President from 1801 to 1809.

Jefferson served as Secretary during a critical time for the new republic. Diplomacy–as it is now–was crucial to national security. Under the Articles of Confederation, he had served as U.S. Minister to France and was an architect of early American foreign policy.

Thus, when George Washington became the first president of the United States, he chose Jefferson for his considerable diplomatic expertise for the Secretary of State cabinet position. Jefferson’s appointment would start a trend in which many Secretaries of State would advance directly to the presidency.

A Clear Line from Secretary of State to President (1800-1831)

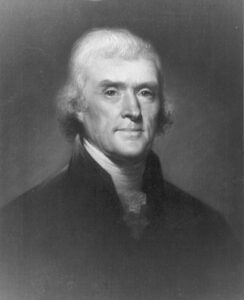

After Jefferson, a long line of Secretaries of State would become president. James Madison served as Jefferson’s Secretary of State from 1801 to 1809. Madison easily won the 1808 presidential election, serving two presidential terms. James Monroe, another Virginian, would serve as Secretary of State from 1811-1817. Monroe would also move from the cabinet position to the presidency in 1817, also serving two terms.

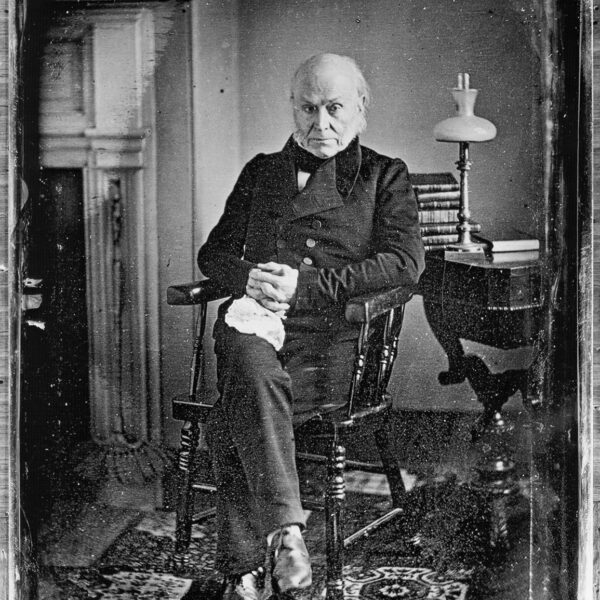

After many years of service as a diplomat, John Quincy Adams served as Secretary of State from 1817 to 1825. He would become president immediately following this term in 1825, but served only one term, losing to Andrew Jackson in 1828.

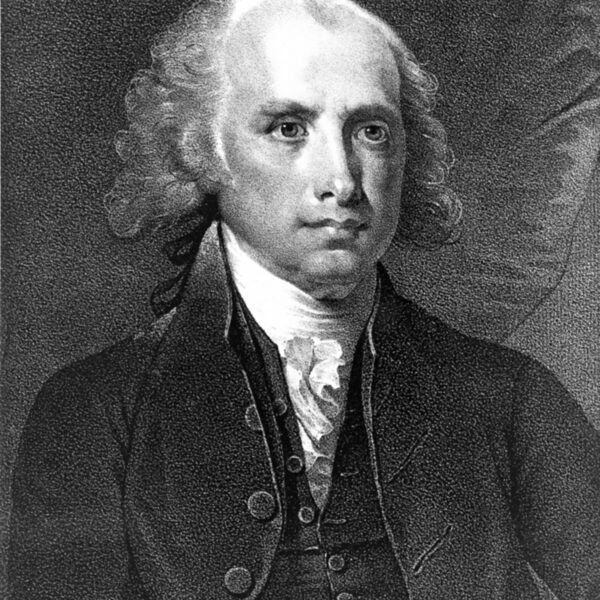

Finally, Martin Van Buren would fill the Secretary of State position from 1829 to 1831. He was the first to move from that position, to Andrew Jackson’s vice-president in his second term, to winning the presidential election in 1836.

Changes in the Presidential Nomination Process (1832-1857)

Through the early 1800s, congressional caucuses were responsible for determining the presidential candidates to represent their political parties. Since former Secretaries of State were known nationally, they became popular nominees.

In 1831, presidential nominating conventions replaced these congressional caucuses to determine party nominees. This move increased the number of individuals, now called delegates, responsible for determining the party candidate. This change caused a shift in the path to the presidency.

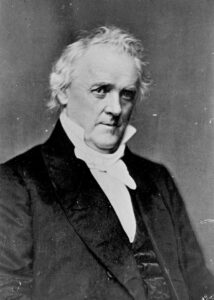

After the presidential nominating field widened, another 20 years would pass until another Secretary of State would become the President. Former Secretary of State and Senator from Pennsylvania James Buchanan would become President of the United States in 1857. He had served as Secretary of State from 1845 to 1849.

To date, Buchanan would be the last Secretary of State to become President of the United States.

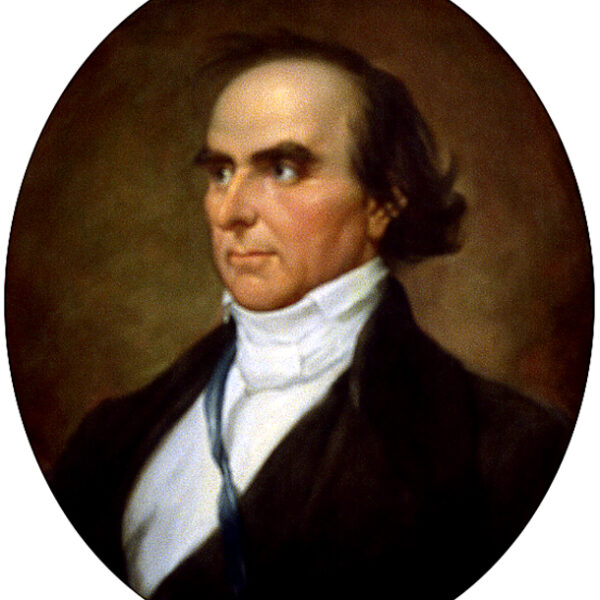

Henry Clay and Daniel Webster were 19th-century Secretaries of State who were unsuccessful in securing the presidency once nominated. Clay served as Secretary of State from 1825 to 1829 but then lost the presidential elections in 1832 and 1844. Daniel Webster served as Secretary of State from 1850 to 1852 but lost his presidential run in 1852. Both long-time senators, their political opponents successfully used their senate voting records against them.

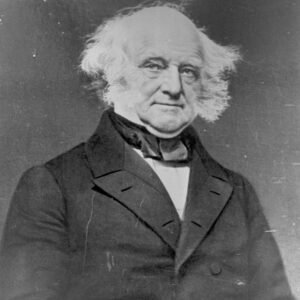

The Modern Era: From Presidential Nominee to Secretary of State

After James Buchanan, few Secretaries of States would run for president, and none would succeed. Senators would become more likely to seek, and win, a presidential nomination.

Beginning after the Civil War, a new pattern emerged in which former presidential nominees would become Secretaries of State after their unsuccessful campaigns for president. As Historian Emeritus of the U.S. Senate Don Ritchie points out, these Secretaries would bring years of political service and experience to the position and more global name recognition: two essential qualities for the nation’s lead diplomat.

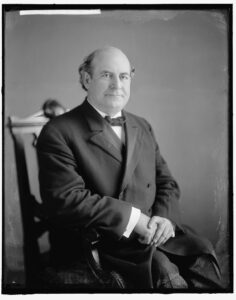

Many of these Secretaries of State, including Secretary Hillary Clinton and Secretary John Kerry, would come with a wealth of political experience. While their many years voting on controversial legislation in the Senate may have complicated their presidential runs, their many years of foreign policy experience made them ideal picks for Secretary of State for presidents who had less experience in foreign affairs. An early 20th-century example is William Jennings Bryan. He unsuccessfully ran for president three times, then became Secretary of State in 1913.

The Future of the Path to the Presidency

The path to the presidency will continue to change. While the Secretary of State’s office may no longer pave an obvious road to the White House, this cabinet position remains essential to the security and prosperity of the United States in this interconnected world.

On January 27, 2021, we hosted a conversation with Historian Emeritus of the U.S. Senate Don Ritchie, moderated by NMAD’s Public Historian Alison Mann. Tune-in to the discussion below for further insights and anecdotes about Secretaries, senators, and the presidency.