1778 Treaty of Fort Pitt: U.S. Treaty-Making with the Lenape Nation

During the Revolutionary War, one of the United States’ earliest treaties was with the Lenape (Delaware) nation aimed at building an alliance against the British: the Treaty of Fort Pitt. Why did this treaty differ from the French alliance earlier that year? And why did it so quickly fall apart?

Crossing Lenape Territory During The Revolutionary War

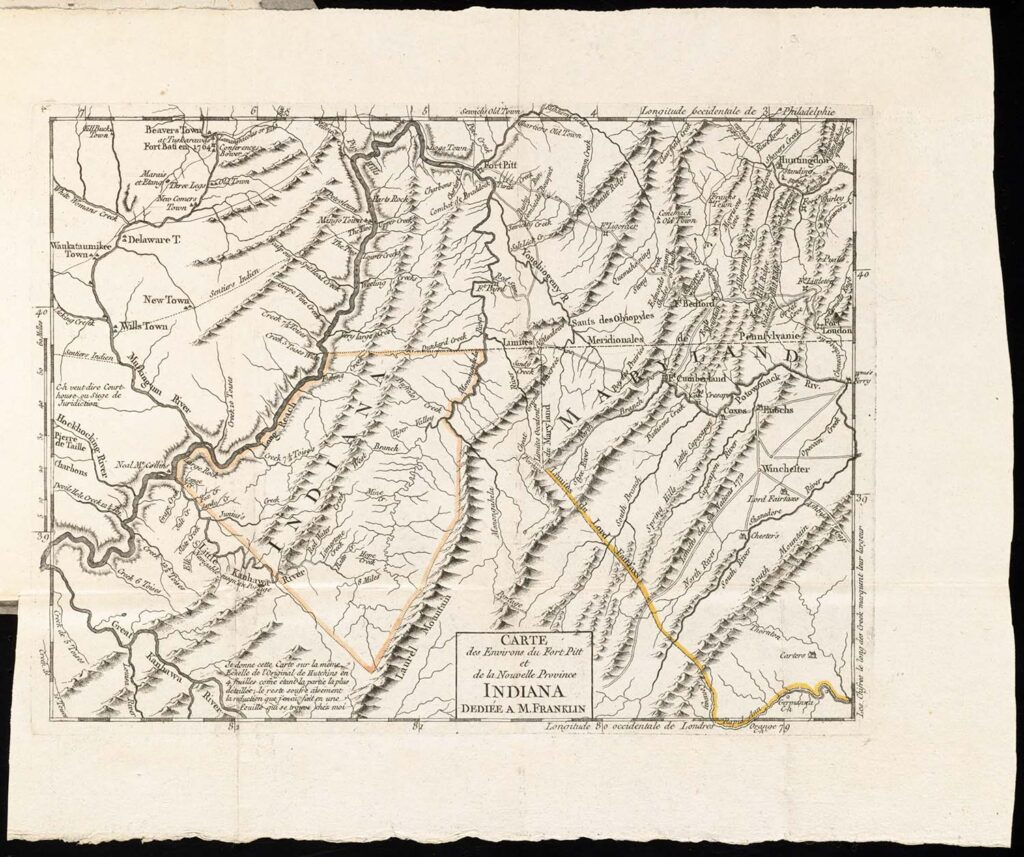

In 1778, after news came from France that the Treaty of Amity and Commerce and the Treaty of Alliance had been secured, the Continental Army planned to march forces west and attack the British at Detroit. But the route crossed Lenape territory in the Ohio Valley.

The United States appointed brothers Andrew and Thomas Lewis as official diplomats to secure permission from the Lenape to cross through their lands. Congress appropriated $10,000 for goods and gifts to present to the Lenape leaders to show the United States’ goodwill.

The Treaty-Making Process

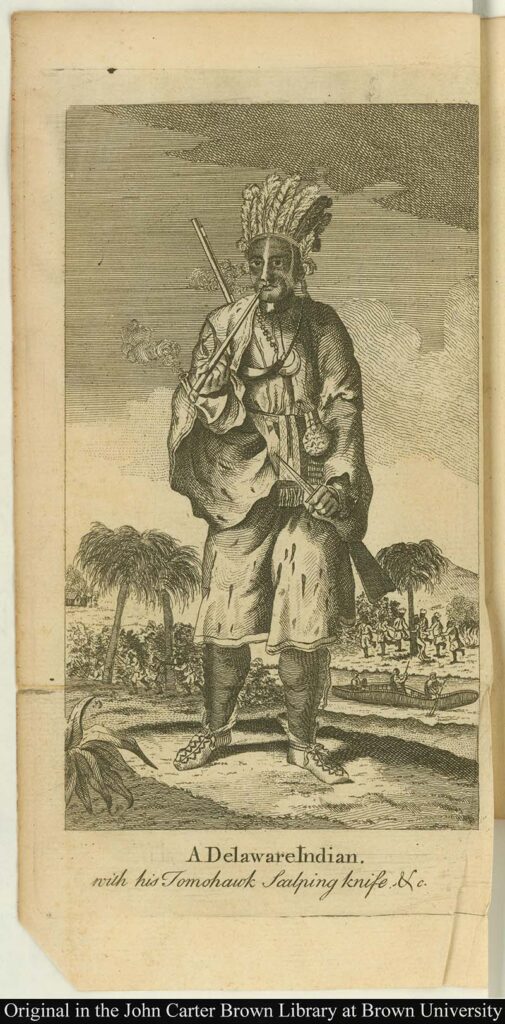

In September, the U.S. diplomats met with Koquethagechton (White Eyes), Gelemend (John Killbuck, Jr.), and Konieschquanoheel or Hopocan (Captain Pipe) at Fort Pitt in western Pennsylvania to begin negotiations.

No one is certain which language the Lenape and Americans spoke during the negotiations, but it was most likely a mixture of Algonquian dialects and English. But both communicated using the diplomatic tools that had been established between Native nations and European nations when the American colonies had been part of the British Empire.

The American diplomats greeted their Lenape counterparts as “Brothers” and “the Chief and Wise men of the Delaware nation.” They explained why they had sought the negotiations, acknowledging that “the Chain of Friendship” (between the Americans and the British) had “Contracted some Rust, of a very Dangerous Nature” and were in need of Lenape assistance.

The Lenape presented the Lewis brothers with a belt of white wampum showing, in black, the 13 United States and the Lenape nation in a visual chain of the alliance. Wampum belts were a symbolic tool of treaty-making in some Native nations that showed parties in a kinship relationship.

The Americans also announced the recent alliance with France and offered to extend that “Bright and Extensive Chain” of “friendship and assistance” to the Lenape nation. The Lenape had an alliance with the French and interpreted this announcement as an expansion of existing Native American and European kinship networks that had been cultivated for centuries.

The negotiations lasted several days. On September 17, 1778, they signed the Treaty of Fort Pitt, promising a “perpetual peace and friendship” between the two nations.

In the text of the signed treaty, the Lenape agreed to permit the Continental Army to cross their lands, guide them to British locations, and to “join the troops of the United States.”

In return, the Americans promised to build a fort in Lenape territory for protection and promised trade goods. In addition, the treaty provided for the creation of a 14th state governed by Native Americans with a political representative in the U.S. Congress.

The Treaty of Fort Pitt Quickly Breaks Down

Like Franklin’s negotiations with the French, the Americans’ diplomacy with the Lenape leaders was conducted with mutual respect and discussions of each nation’s self-interest. In both cases, the treaty-making process involved diplomacy using traditional norms. Unlike the French alliance that lasted beyond the conclusion of the American Revolution, however, the Treaty of Fort Pitt began to crumble within weeks.

First, the Lenape leader White Eyes died. While American officials insisted White Eyes died from smallpox as the cause, evidence indicated members of the militia murdered him, and the circumstances remain unclear to this day. This act showed the Lenape that the Americans did not value nor honor the importance of kinship alliances.

Second, the American negotiators lacked cultural awareness of the Lenape’s understanding of what happened after a treaty was signed. To the United States, a signed paper treaty made the terms of the agreement final and ended the treaty-making process. This is what the Americans and French mutually understood after the signing of their alliance. However, for the Lenape, the relationship established during the negotiations was dynamic and required cultivation to sustain the alliance. The paper treaty represented the beginning of the relationship, not its end.

Most importantly, the Americans saw no evidence the Lenape intended to honor the alliance, and considered treaties to be reciprocal agreements. In the midst of a military campaign for independence, the United States turned towards other potential Native American allies. The trade goods never arrived. The U.S. Congress never discussed the creation of a sovereign 14th Native American state. The United States hastily built a fort in Lenape territory, Fort Laurens, but the British quickly took it over. The U.S. government also failed to prevent Americans from occupying Lenape lands.

The Lenape Attempt to Salvage the Treaty

The Lenape people initially tried to salvage their alliance with the United States.

First, a Lenape delegation went to the Continental Congress asking for them to uphold their promises. In addition, some Lenape warriors assisted the Continental Army; however, after it became clear that the alliance had broken, more Lenape joined the British against the Americans. The United States then declared that the Lenape had broken the terms of the treaty and made no diplomatic attempts to mend the relationship.

In 1782, Pennsylvania militia massacred a peaceful Christian Lenape community in Gnadenhutten. Many left the Ohio Valley afterward. Their Lenape descendants later founded the Delaware nation at Moraviantown, Ontario, the Delaware Tribe of Indians of northeastern Oklahoma, and the Delaware nation of central Oklahoma.

Violence committed against the Lenape, lack of cultural awareness, and poor diplomatic communication were only some of the problems that led to the breakdown of the Treaty of Fort Pitt. Similar problems continued between the United States and sovereign Native Americans for years to come.

The National Museum of American Diplomacy thanks Dr. Margaret Ball, Historian at the Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State, for her thoughtful contributions to this blog.

Sources and Further Reading

Colin G. Calloway, The American Revolution in Indian County: Crisis and Diversity in Native Communities (Cambridge Studies in North American Indian History, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Congress, United States Continental, Worthington Chauncey 1858-1941 [Ford, and Gaillard 1862-1924 Hunt Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789; Volume 9. Biblio Bazaar, 2016).

Brian Delay, “Indian Polities, Empire, and the History of American Foreign Relations,” in Diplomatic History 39, no. 5 (November 2015): 927-42.

Gregory Evans Dowd, A Spirited Resistance: The North American Indian Struggle for Unity, 1745-1815 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993).

Randolph Chandler Downes, Council Fires on the Upper Ohio: A Narrative of Indian Affairs in the Upper Ohio Valley until 1795 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1969).

Richard S. Grimes, The Western Delaware Indian Nations, 1730-1795: Warriors and Diplomats (Rowman & Littlefield, 2017).

Suzan Shown Harjo (ed.), Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2014).

Dorothy V. Jones, License for Empire: Colonialism by Treaty in Early America (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1982).

Francis Paul Prucha, American Indian Treaties: The History of a Political Anomaly (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1994).

Otis K. Rice, The Allegheny Frontier: West Virginia Beginnings, 1730-1830 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2021).

Amy C. Schutt, Peoples of the River Valleys: The Odyssey of the Delaware Indians (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007).

Richard White, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006)