Simulation

Barbary Pirates Hostage Crisis: Negotiating Tribute and Trade

In 1793, Algerine corsairs captured 11 more American ships and 100 citizens, prompting a commercial and humanitarian crisis that could not be ignored.

May 13 marks the 218th anniversary of President Thomas Jefferson ordering U.S. naval vessels to stop Barbary interference with American trade in the Mediterranean. Jefferson’s decision to use force against the Barbary nations of Algiers and Tripoli (semi-autonomous Ottoman Empire states) came after 15 years of negotiations and the Americans’ refusal to continue paying monetary tribute as the price for trading.

Prior to the early 1780s, American merchants enjoyed trading wheat, flour, and pickled fish throughout the Mediterranean in return for wine and salt under the protection of the British navy. Once the colonies won their independence, they lost this protection and fell prey to Barbary pirates lying in wait at the mouth of the Strait of Gibraltar. These “pirates” — as the western world called them — were actually corsairs or privateers. Pirates are rogue actors not beholden to any nation and operate illegally, while corsairs are ship owners who work for and split their profits with the head of government. But to Americans, who believed firmly in free trade, the kidnapping of sailors and theft of ships was nothing less than piracy. Unfortunately, without a navy to protect private shipping, there was nothing American merchants could do except to try and negotiate treaties agreeing to pay enormous sums of money. U.S. diplomats accomplished such treaties with Tripoli, Algiers, and Tunis in 1796 and 1797. The diplomats agreed to pay ransom for 89 American sailors (some of which had been held for 11 years) and a yearly tribute amounting to about 16 percent of the entire appropriated U.S. budget.

The years following these initial treaties were a tense period for American merchants and sailors, especially those who had been previously captured. If their ship fell into the hands of Barbary corsairs, they would need to prove their American identity, which a passport could provide. Before 1941, the United States did not require its citizens to carry a passport for travel except during wartime, making passports from the late 18th century/early 19th century extremely rare.

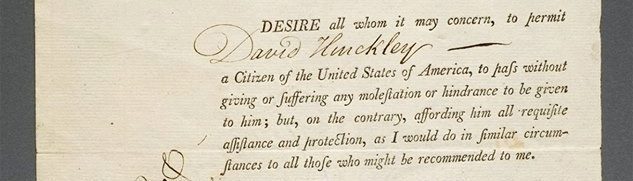

Rufus King, then American minister to Great Britain, issued this 1798 passport to David Hinckley, a wealthy Boston merchant who frequently traveled to London on business. It is the oldest in our extensive collection and also one of the more intriguing. Barbary corsairs had captured David Hinckley in the early 1790s, enslaving him into hard labor for two years until diplomats secured his freedom through ransom. In 1798, Hinckley ensured he had an official U.S. government passport on his person to prove he was an American citizen and protected under the 1796 and 1797 treaties.

FROM THE COLLECTION

1798 Passport issued to David Hinckley

Passports would not, however, provide protection if nations broke treaties. The United States government quickly fell behind on its payments and the Barbary States resumed piracy around 1800. But unlike the 1780s, the United States had built a navy, and Thomas Jefferson was ready to use it in defense of American trade without tribute. The First and Second Barbary Wars (1801-1805 & 1815) concluded favorably for the United States, and diplomats drew up new treaties declaring that none of the nations would show any “favor or privilege in navigation or commerce” to any particular country. And cautious traders, like David Hinckley, could now travel more safely in the Atlantic and Mediterranean, with or without passport in hand.