The Rise and Fall of the Berlin Wall

AMERICAN DIPLOMACY IN GERMANY IN THE COLD WAR

This is the history of the Berlin Wall told through the voices of U.S. diplomats, featuring artifacts from the National Museum of American Diplomacy’s collection. As the political climate changed over the years in a divided Germany, U.S. diplomats continued to work across barriers to advance our nation’s interests even amid the tensions of the Cold War that the Wall embodied. More than thirty years after Germany’s reunification, American diplomacy continues to be a global force, continually evolving and shaping the events of today.

- 1945

- 1950

- 1955

- 1960

- 1965

- 1970

- 1975

- 1980

- 1985

- 1990

- 1995

- 2000

- 2005

- 2010

- 2015

1945

The Cold War Begins

Post-World War II diplomacy faced innumerable challenges as the Cold War strained diplomatic relations between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union. Germany’s surrender in May of 1945 left the country without a government or clear borders between European nations. The “Big Three,” U.S. President Harry Truman, Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (soon replaced by Clement Attlee) met in Potsdam, Germany to discuss Germany’s future. Resulting negotiations from the Potsdam Conference, held between July 17 and August 2, divided Germany and Berlin among the United States, Soviet Union, Britain, and later France. Initially, these countries hoped relations with Joseph Stalin might improve, but instead, they deteriorated as an “Iron Curtain” descended across Eastern Europe.

“We were very much in the Cold War…”

– Karl Mautner

1945

Germany Divided

U.S. diplomat Jacques Reinstein recalled how the 1945 Potsdam Agreement dividing Germany among the Western Allies, “came as a considerable shock to the State Department,” which had planned to proceed more slowly. By 1949, responding to continuous Soviet attempts to cut power, food, transportation, and fuel to Berlin, the Allies created the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), commonly referred to as West Germany, with a capital in Bonn and a mission in Berlin. In response, the Soviets established the German Democratic Republic (GDR), referred to as East Germany, maintaining East Berlin as its capital.

July 1945

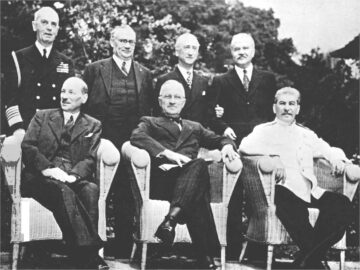

Potsdam Conference

The “Big Three” convened a conference in Potsdam, Germany, to determine punishment for the defeated Nazi regime, the establishment of post-war order, and how to rebuild Europe’s ravaged societies.

Seated are (left to right): British Prime Minister Clement Atlee; U.S. President Harry Truman; and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin. Standing behind them are (left to right): Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy, U.S. Navy, Truman’s Chief of Staff; British Foreign Minister Ernest Bevin; U.S. Secretary of State James F. Byrnes and Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov.

FROM THE COLLECTION

Germany Basic Handbook

Communist Presence Grows

In this audio clip, U.S. Army Officer Karl Mautner (82nd Airborne) discusses the division between the USSR-allied East Germany and United States-allied West Germany extended to the residents of these occupied areas.

This East German flag was flown over an office building in Berlin that would later become the U.S. Embassy.

Porcelain Replica Of Berlin Freedom Bell

This Meissen ware bell replicates the original Freedom Bell that New Yorker Walter Dorwin Teague designed in the late 1940s at the beginning of the Cold War. The original 10-ton bell was a symbol of the U.S. campaign to open Europe through radio stations like Radio Free Europe. In 1950, U.S. radio promoters installed the Bell in West Berlin, where its outline became the first logo for Radio Free Europe and its ring a symbol of freedom, broadcast daily at 6 pm.

Gift of Governing Mayor of Berlin Eberhard Diepgen to U.S. Secretary of State Colin L. Powell. Catalog Number: 2005.0007.016

c. 1950

Printing Block With Radio Free Europe Logo

The iconic shape of the Freedom Bell appears on this Radio Free Europe printer’s block as the station’s logo. The two-part messaging flanking the Freedom Bell reads, “Join the Crusade for Freedom” and “Help Truth Fight Communism.”

Collections of the National Museum of American Diplomacy. Catalog Number: 2009.0014.07

Berlin Divided and Isolated

American diplomats and military personnel worked in Germany after World War II, confronting the intensifying ideological conflict between East and West, first through a military government, then through a high commission. The United States maintained an embassy in West Germany and a mission in Berlin, not diplomatically recognizing East Germany until 1974. After Stalin’s death in 1953, the new Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, backed East German leader Walter Ulbricht. Both intensified the hard line against the Allies and their presence in Berlin.

1958-1960

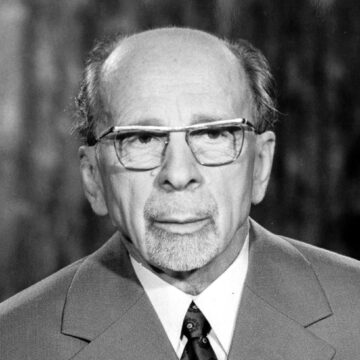

Walter Ulbricht Undermines Western Presence in Berlin

East German Walter Ulbricht, shown in this picture, who was Chairman of the Council of State from 1960-1973, irritated U.S. diplomats like Kempton Jenkins, a Political officer stationed in Berlin (1958-1960) by undermining the Allies’ authority in West Berlin.

In this audio clip, Kempton Jenkins describes this tumultuous period.

Hardening of Relations: West and East Germany

East Germany’s communist regime coveted the entire city of Berlin, since it lay embedded within its territory. In 1948, Stalin blockaded all land and water routes into West Berlin, depriving its dwellers of food and fuel. President Harry S Truman would not “abandon Berlin” and the United States and Britain mounted an intensive airlift. Under the command of General Lucius Clay, the Berlin Airlift provided needed supplies for more than 2 million Berliners over 15 months, transporting 2.3 million tons over 277,569 total flights. Despite the airlift’s success, the Soviets continued efforts to curtail communication and travel.

The Heroism of General Lucius Clay

General Lucius Clay, pictured here, was the Military Governor of the American Zone from 1947-1949. He was an American hero for Berliners during the 1948 Airlift, which bypassed a Soviet blockade to supply West Berlin with food, fuel, and other aid that U.S. diplomat Yale Richmond (Cultural Affairs Officer, West Germany, 1949-1954) recalls in this audio clip.

1949

“Operation Vittles” Cookbook

1990-1999

Bronze Sculpture Commemorating the Berlin Airlift

This bronze commemorative piece replicates the memorial to the Berlin Airlift, also known as “Operation Vittles.” Each prong represents one of the three air corridors open for cargo planes. On the original memorial, constructed in 1951 and located at the now-closed Tempelhof Airport in Berlin, the names of the U.S. and British Airmen killed during the airlift are inscribed on the base of each prong. Two identical versions of the original memorial stand at airports in Frankfurt and Celle.

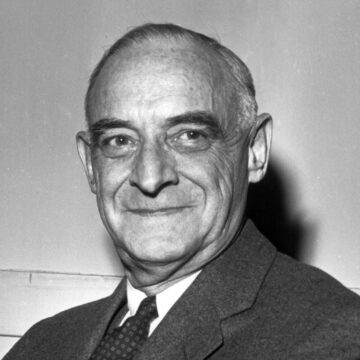

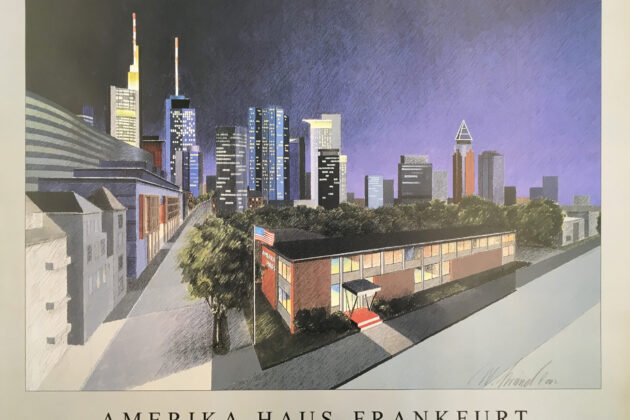

Hans N. Tuch and the Amerika Haus

In the late 1940s and onward, U.S. diplomat Hans N. “Tom” Tuch (Director, Amerika Haus, United States Information Agency, West Germany, 1949-1952), portrayed in this photo, worked to instill a sense of democracy in West Germany through the America House [Amerika Haus in German] programs and services that he described in this audio clip.

FROM THE COLLECTION

Amerika Haus Frankfurt Poster

1961

Walling People In

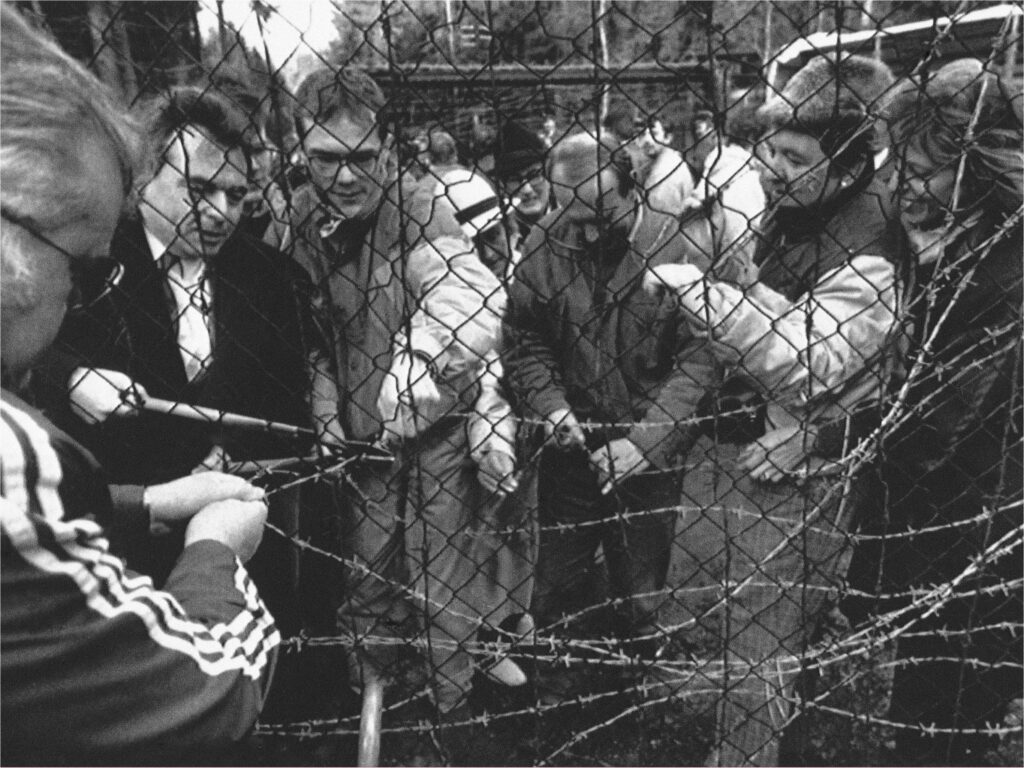

When the Berlin Wall went up on August 13, 1961, U.S. diplomats watched human tragedies unfold as family members wept across barbed wire. Many wondered if the next war would start because of Berlin. Despite the Wall’s imposing presence, President John F. Kennedy commented to Kenny O’Donnell, his appointments secretary: “It’s not a very nice solution, but a wall is a hell of a lot better than a war.” Assistant Secretary Thomas Niles spoke for many when he recalled, “Once the Wall was built, it created a sort of stability. It imprisoned 17 million people in East Germany, but it did guarantee, in its perverse and obnoxious way, a stability in a potentially unstable area.”

“THEY WERE LOSING HUGE NUMBERS OF EAST GERMANS…”

– BRUCE FLATIN

June 1961

A Cold Winter Looms

In June 1961, Soviet Premier Khrushchev, met with the new and unseasoned President John F. Kennedy. Kennedy thought he could get the Soviets to make concessions on allowing West Berlin better access to the West, but Khruschev instead threatened to support a full communist takeover of the entire city. He also declared the Soviets’ intent to sign a separate peace treaty with the East German government.

By the end of the meeting, Khruschchev said to Kennedy, “We’re moving forward. You press us, that’s your problem.” Kennedy said in response, “It’s going to be a very cold winter.” He left the summit very shaken and the situation in West Berlin was more perilous than before.

Hearing this, the number of refugees fleeing East Germany tripled. The Director of Radio in the American Sector, Robert Lochner, later observed, “It became increasingly apparent that the Soviets had to stop the depopulation of East Germany if they were not to lose total control.”

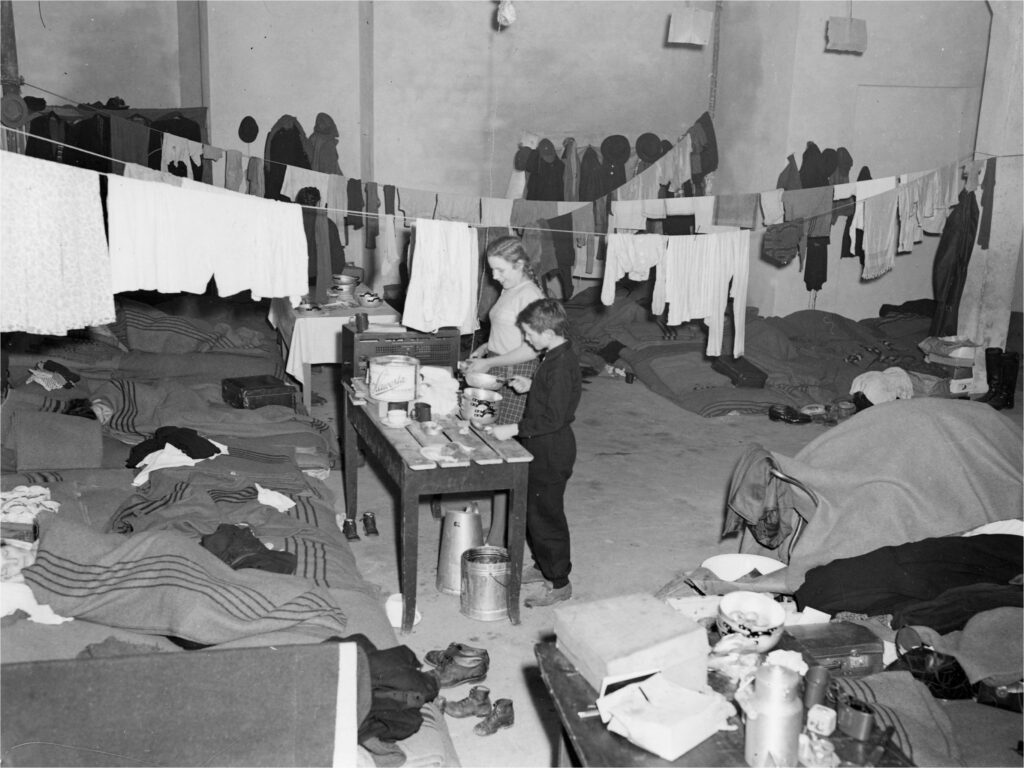

August 14, 1961

Refugees Flee East Germany

After Khrushchev and Kennedy’s 1961 meeting, thousands of East Germans began to flee. Pictured here are several hundred people at a refugee camp in West Berlin. U.S. diplomat Bruce Flatin (Public Safety Section, Berlin, 1964-1969) recounts the refugee crisis and resulting “brain drain” in this audio clip.

August 1961

The Wall Goes Up

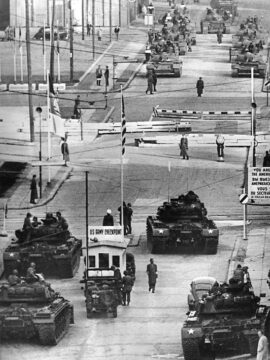

When workers divided Berlin on August 13, 1961, U.S. diplomats discovered construction of the barrier underway during the night. U.S. radio, broadcasting live news segments, warned listeners who might want to escape. Allied protest against the Wall was delayed more than 48 hours, due in part to President Kennedy’s reluctance to provoke a confrontation with the Soviets. This delay especially angered West Berlin Mayor Willy Brandt. In response, Kennedy sent Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson and General Clay to Berlin and mobilized U.S. troops. In October 1961, U.S. and Soviet tanks faced each other over a border crossing incident involving U.S. diplomats. The confrontation took place at Checkpoint Charlie, the U.S. crossing point, but both sides withdrew.

1961

Berlin Wall Goes Up

U.S. diplomat Robert Lochner, seen here, was the Director of the Radio in the American Sector (RIAS) in Berlin in 1961.

In this clip, Robert Lochner recalls the first night of construction of the Wall, and his reporting of it for RIAS.

Consequences of the Wall

When completed, the Wall ran 26.8 miles across Berlin (96.3 miles total across Germany) evolving from barbed wire into over 13-foot high parallel walls with a “dead man’s zone” in between. Marksmen in towers had orders to shoot to kill escapees. Some daring West Berliners wrote “KZ,” meaning “concentration camp,” on the West side of the Wall.

Fleeing a repressive regime, many East Germans—at least 100 and likely more—died violently attempting to leave between 1961 and 1989. More fortunate escapees relied on tunnels, retrofitted cars, hot air balloons, and watercraft. Throughout its existence, the oppressive Wall disheartened and angered the German people.

Crisis Management in West Berlin

Brandon Grove, Jr. (U.S. Liaison Officer, Berlin, 1965-1969) portrayed in this photo, remarks in this audio clip how crisis management was an important aspect of conducting day-to-day diplomacy in West Berlin in the late 1960s. Grove served first in the West, then later in East Berlin.

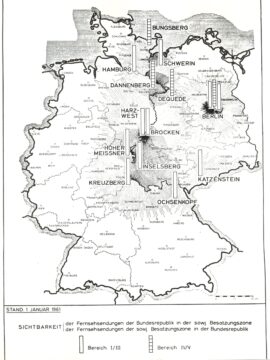

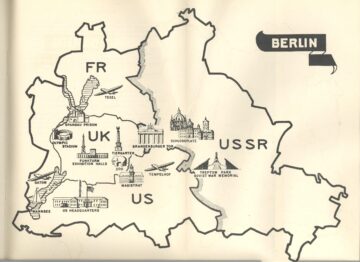

The Allied Presence in Berlin

The flags on the map emphasize the close proximity of the Allied sectors in West Berlin to the Soviet-held East Berlin.

William Tyler, Assistant Secretary of State for European Affairs from 1962 to 1965, reflects in this audio clip on the tight grip each Ally held on its sector.

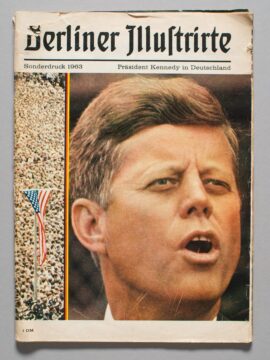

1963

“Ich Bin Ein Berliner.” – President John F. Kennedy

When John F. Kennedy visited Berlin in 1963, Ambassador’s Staff Assistant Paul Cleveland described the President’s approach as a “‘political campaign’ to try to bolster German morale.” Speaking in a plaza named for him later after his death, Kennedy gained immense popular solidarity with the city uttering, “Ich bin ein Berliner” [“I am a Berliner”]. Intelligence officer Thomas Hughes recalled how Kennedy turned from relative disinterest in Germany to making it a focus of his foreign policy. Kennedy’s successor, however, President Lyndon B. Johnson, pursued other diplomatic interests.

1963

Magazine: Berliner Illustrierte, Präsident Kennedy In Deutschland, Sonderdruck 1963

Title translation: Berliner Illustrated, President Kennedy in Germany, Special Print 1963. Visit of President John F. Kennedy to Berlin.

June 26, 1963

President John F. Kennedy Visits West Berlin

President Kennedy, left, seated in a car with Berlin Mayor Willy Brandt, center, and German Federal Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, right, visiting West Berlin in 1963. On the occasion of Kennedy’s visit, East German border guards suspended large panels of red cloth from the Brandenburg Gate and mounted an English-language propaganda poster directly in front of it. The poster maintained that the denazification and demilitarization of Germany that had been called for in Potsdam had only occurred in East Germany.

1963

The Story Behind “I Am A Berliner”

This photo of the speech that President Kennedy delivered in Berlin in 1963 shows how U.S. diplomat Robert Lochner added a famous sentence to it at Kennedy’s request. In this audio clip, Lochner also recounts President Kennedy’s reception during his tour of Western Germany.

1961-1989

Diplomacy Despite the Wall

Willy Brandt’s policy for change titled neue ostpolitik in the late 1960s resulted not only in renunciation of force treaties between West Germany and the Soviet bloc but also in a landmark agreement clarifying the special status of Berlin. This diplomacy eased relations between Bonn and East Berlin as well as across the Wall that divided the former German capital, laying some of the groundwork for German unification in 1990.

In 1974, the two Germanys gained diplomatic recognition and UN membership. U.S. diplomats emphasized that their new East Berlin embassy was to East Berlin, not in it, clarifying Berlin’s special status since the U.S. embassy could not be in the sector held by the occupying Soviets. U.S. diplomatic relations with a rigid East Germany began.

“Neue Ostpolitik”

– Willy Brandt

A System of Deliberate Contacts

All diplomats observe and report to their national headquarters, but U.S. diplomats had limited opportunities to visit East Germany and assess the situation on the ground. A major way to travel there was for U.S. diplomats to visit the Leipzig Trade Fair through special visa arrangements. There they could observe the economic developments of Soviet bloc countries.

Western radio broadcasts (then later, television) became another important method of Allied communication with all parts of Germany. The United States was committed to reaching the people of the East; to provide communication with a Western viewpoint unfiltered by communist rhetoric.

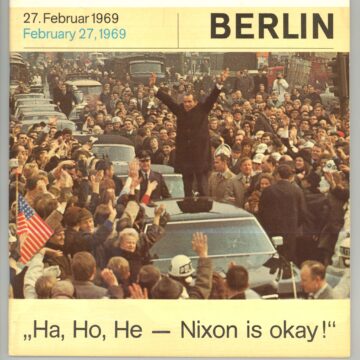

1969-1971

Neue Ostpolitik: New Eastern Policy

The cover of this booklet depicts U.S. President Nixon’s triumphant 1969 visit to West Berlin. It also illustrates U.S. diplomat Robert Barkley’s comment in this interview clip about how German neue ostpolitik [New Eastern Policy] and U.S. détente overlapped. Barkley served in both Bonn and East Berlin.

In the audio clip, Barkley recalls his time at the German Affairs Bureau and the changing relationships between the United States, USSR, and West Germany, reflective of Willy Brandt’s ostpolitik.

1979

U.S. Computer Exhibit At Leipzig Trade Fair

Through an active exhibition program, the U.S. Information Agency circulated many shows in Soviet bloc countries to inform people about American life, economy and culture. As part of the U.S. Embassy East Berlin’s public diplomacy, this exhibition on U.S. computers reached thousands of visitors from behind the Iron Curtain.

David B. Bolen Papers, Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University

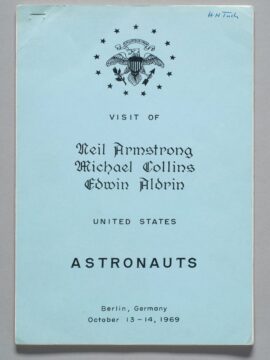

1969

Landing on the Moon

The U.S. astronauts who made the historic 1969 moon landing embarked on a global goodwill tour soon after their return to earth, with two stops in Germany. U.S. diplomats helped guide their activities, as detailed in this blue-covered official itinerary that belonged to U.S. diplomat Hans Tuch, Mission Berlin’s Public Affairs Officer.

U.S. diplomat Jonathan Dean (Political Counselor, 1968-1972) reflects in this audio clip on the importance of gaining German support through several different avenues of diplomatic contact.

1969

Willy Brandt and Neue Ostpolitik

Willy Brandt became Chancellor of West Germany in 1969. His party developed the policy of neue ostpolitik [new Eastern policy], accepting Germany and Europe’s divisions but working to establish relations with Soviet bloc countries for practical ends. He saw West Germany’s interests as: a continued alliance with the West, reducing tensions across the “Iron Curtain,” expanding trade with communist countries to the east, and ultimately, German reunification. In their oral histories, U.S. diplomats referred to the process of neue ostpolitik as Brandt described it—“change through rapprochement” and a “policy of small steps.”

Willy Brandt and his Ostpolitik

In the late 1960s, Brandon Grove, Jr., then serving as U.S. Liaison to the City Government of West Berlin, described in this audio clip how he interacted frequently with then-Berlin Mayor Willy Brandt, seeing first-hand his goals for ostpolitik. Brandt later became German Chancellor from 1969-1974.

1971

Brandt Receives the Nobel Peace Prize

This photo of West German Chancellor Willy Brandt accepting the Nobel Peace Prize in 1971 reflected the high esteem that Brandon Grove, Jr., accorded the German leader.

In this clip, Brandon Grove, Jr. recounts his thoughts of West German Chancellor Willy Brandt.

1971

Normalization: Coming to Terms with Two Germanys

“Normalization” of German-to-German and West German-to-Soviet bloc relations came about after Brandt’s government recognized Europe’s borders as firm, entered non-aggression treaties and acknowledged the two-state situation in Germany. In 1971, the Western Allies and Soviet Union signed the Quadripartite (Four Power) agreement clarifying the status of Berlin, leading to additional German-to-German agreements on mail and telephone communications; transportation and permission for ordinary West Berliners to visit East Berlin. Quality of life increased in “small steps” for everyone involved.

1977

Ambassador Bolen Presents his Credentials

U.S. Ambassador David Bolen (right) greets East German Chairman of the Council of State Erich Honecker upon Bolen’s presenting his credentials in 1977. Bolen’s appointment followed years of diplomatic negotiations between East and West to help ease tensions.

U.S. diplomat Jonathan Dean, reflected on U.S. reservations about conducting diplomacy in this hard-line communist country in the audio clip.

1974-1976

The First U.S. Ambassador to East Germany: John Sherman Cooper

The first U.S. ambassador to East Germany, John Sherman Cooper, set the tone for American diplomatic relations with East Germany.

U.S. diplomat Brandon Grove, Jr., posted to East Berlin in the German Democratic Republic as Deputy Chief of Mission with Cooper, recounts that despite sending an ambassador to East Germany, the United States was displeased about East Germany’s recognition globally as a legitimate country.

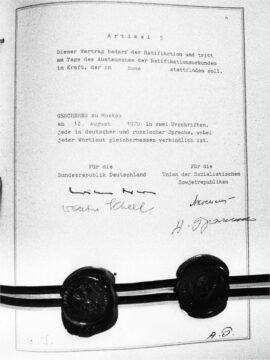

August 12, 1970

Signing of the Treaty of Moscow

Chancellor Willy Brandt (left) and Soviet Prime Minister Alexej Kosygin (right) sign the Treaty of Moscow, an agreement between West Germany and the Soviet Union in 1970. The treaty renounces violence and is seen as a first step toward better cooperation between Western and Eastern Europe. Leonid Brezhnev, Soviet Union communist leader, stands hands folded.

AP photo

November 8, 1972

Initialing the Basic Treaty

Before there could be significant normal relations between the two Germanys, both sides had to agree to a compromise. This was achieved in the signing of the Basic Treaty in 1972 when both sides agreed to recognize each other as sovereign states with two separate and distinct governments. Talks lasted a long time, mostly because West Germany did not want to give up on eventual reunification under a democratic form of government. At a meeting in Bonn on November 8, 1972, East German State Secretary Michael Kohl (left) and West German State Secretary Egon Bahr (right) initialed the Basic Treaty between West Germany and East Germany. The treaty was officially signed on December 21, 1972.

Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY

Creating an Amenable Climate

When the interim Charge d’Affaires, Brandon Grove, Jr., helped open the U.S. embassy to East Germany, he required staff to live in that sector. The new embassy was determined to cultivate respect and a favorable U.S. image among East Germans. Diplomats rely on many skills to do this—among them, language, intelligence, alliances with other nations, and public diplomacy. However, the ever-present Stasi (East German secret police) complicated their efforts, tailing diplomats’ activities and tapping their phones. The East German government also carefully monitored the activities of U.S. citizens traveling to East Germany and East Berlin. Their travel was not restricted, but stringent visa requirements regulated their movements.

The East German Diplomatic Strategy

U.S. Ambassador to East Germany Rozanne Ridgway greets Erich Honecker, East Germany’s leader. Ridgway described life’s challenges in East Germany and how she pursued a focused diplomatic strategy in this interview clip.

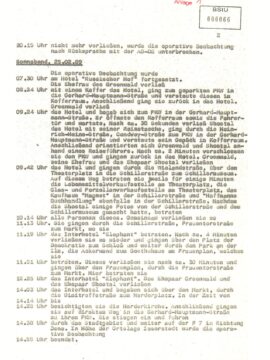

1989

Stasi Operational Assessment Document on Surveillance of U.S. Diplomat G. Jonathan Greenwald

Nearly 20 years after serving in East Berlin, U.S. diplomat G. Jonathan Greenwald received a several inches thick file the Stasi had compiled on him, his family and friends. This report covers a visit his wife and some friends paid to the city of Weimar, East Germany, in February 1989. The Stasi had taped Greenwald’s telephone conversation planning the trip and tailed them during the excursion. The Stasi produced a detailed report beginning with the notation of their arrival in Weimar at 17:45 (5:45 p.m.) in the afternoon and continued with near minute-by-minute observations of their activity until they departed at 14:55 (2:55 p.m.) the next day. The “Operational Assessment” (pictured) concludes with an implied sense of disappointment: “The impression was gained that Greenwald and the persons accompanying him used their stay in Weimar to make themselves familiar with the worthwhile things to see and the places of activity relating to the great classic figures of German literature…No contacts or attempts at contact by Greenwald and the persons accompanying him with other persons were established during the time they were observed…”

Greenwald’s appetite for German sausage gained him the Stasi nickname, “Caesar–the Bockwurst Fan.” The second image shows a Stasi surveillance photograph of U.S. diplomat G. Jonathan Greenwald.

Surveillance in East Berlin

The words reproduced in the image here are from the surveillance file on U.S. diplomat G. Jonathan Greenwald, East Berlin, compiled by the Stasi, or East German secret police. U.S. diplomat Brandon Grove, Jr., posted to East Germany, reflects on living in East Berlin with Stasi presence everywhere in this interview clip.

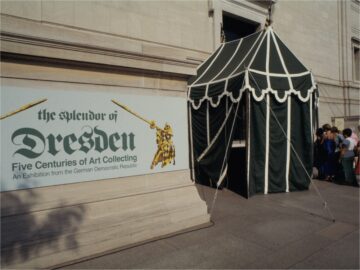

Public Diplomacy in East Germany

The colorful exhibition “The Splendors of Dresden” opened the new East Wing of Washington, DC’s National Gallery of Art in 1978. Public diplomacy efforts, like the Dresden exhibit, were an essential part of thawing diplomatic relations between the United States and East Germany.

In this audio clip, Edward Alexander, Public Affairs Officer, United States Information Agency, reflects on how cultural exchanges, such as the provision of library books and film festivals, furthered diplomacy efforts.

FROM THE COLLECTION

United States Information Service Seal

1975

Helsinki Accords

The lives lost crossing the Wall represented denial of the most basic human rights to live and travel in freedom. The Soviets touted the many-faceted 1975 Helsinki Accords (signed by 35 countries: the United States, Canada and nearly all of Europe) as a diplomatic victory, since they recognized post-war borders in the Soviet bloc. Chagrin soon replaced Soviet self-congratulation when courageous dissidents and liberals from Eastern Europe demanded communist governments adhere to the Accords’ requirement to uphold fundamental freedoms and human rights.

Soviet Reactions to the Helsinki Accords

Thirty-four of the foreign ministers who negotiated the Helsinki Accords gathered in this joint 1973 photo in Finland. U.S. diplomat in East Berlin G. Jonathan Greenwald explained how U.S. negotiators gauged Soviet reaction to the Accords in the audio clip.

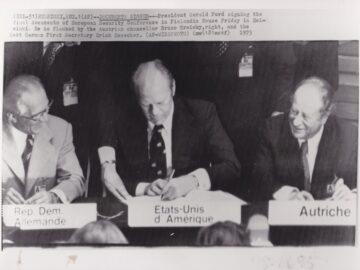

Human Rights and the Helsinki Accords

Signers of the 1975 Helsinki Accords in Finland include East German General Secretary Erich Honecker (left), U.S. President Gerald Ford (center) and Austrian Chancellor Bruno Kreisky (right).

U.S. diplomat Thomas Niles, who served in the Office of Soviet Union Affairs, comments in the interview clip on the importance of human rights in this multinational agreement.

The Impact of the Helsinki Accords

U.S. diplomat Winston Lord, pictured here, served on the policy planning staff to U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger from 1973 to 1977. He describes in the audio clip how the Helsinki Accords of 1975 eventually helped support dissidents in Soviet bloc countries.

1987-1989

Tear Down This Wall

In 1987, U.S. President Ronald Reagan publicly urged Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down” the Berlin Wall in a speech using West Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate as a backdrop. In the mid-1980s, through glasnost—openness and freedom—and perestroika—economic restructuring—Gorbachev had demonstrated willingness to loosen government strangleholds in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, including East Germany. While his openness was praised in the West, he met resistance from East German leader Erich Honecker and his regime. The initial freedoms Gorbachev encouraged in Eastern Europe and Germany led to an unforeseen outcome on November 9, 1989 when the Wall fell.

“Mr. Gorbachev, Tear Down This Wall”

– U.S. President Ronald Reagan

1980

“The New Is Knocking”

By the 1980s the Quadripartite Agreement of 1971 enabled more legal border crossings, including thousands of East Germans working in the West. Gorbachev, in expressing hope, said, “It is not easy to change the approaches on which East-West relations have been built for fifty years. But the new is knocking on every door and window.” U.S. diplomat G. Jonathan Greenwald reported back to Washington, DC that in East Germany Gorbachev was contemplating changes “from the top, the kinds of changes [he] was trying to institute in the Soviet Union.”

1981

Schmidt and Honecker Meet in East Germany

West German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, left, smiles alongside East German General First Secretary Erich Honecker during their 1981 meeting in East Germany.

U.S. diplomat G. Jonathan Greenwald, East Berlin, describes in this interview clip how Honecker visited West Berlin six years later.

Gorbachev and Honecker Clash

U.S. diplomat J.D. Bindenagel, pictured here in 1996 when he was chargé d’affaires to Germany, comments in the interview clip on the antagonism in 1989 between Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev and East German General Secretary Erich Honecker. Bindenagel served as the Deputy Chief of Mission to Germany from 1989 to 1990.

June 12, 1987

U.S. President Ronald Reagan Delivers “Mr. Gorbachev, Tear Down This Wall” Speech

Play VideoFROM THE COLLECTION

President Reagan Visit to Berlin Folio

May 31, 1988

Ronald Reagan And Mikhail Gorbachev In Red Square, Moscow

U.S. President Ronald Reagan (left) and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev (right) stand alone during their impromptu walk in Red Square in Moscow. Although U.S.-Soviet relations were strained in the late 1980s, the two established a good personal rapport.

1989

Air Beginning to Rise

In September 1989, communist Hungary opened its border to Austria and some 50,000 East Germans, who were permitted to travel to their communist neighbors, crossed to freedom. Later, thousands seeking asylum in Prague and Warsaw rode trains to the West. In the same year, Gorbachev visited East Germany to attend the 40-year celebration ceremony of the East German regime. Urging Honecker to accept reforms, Gorbachev warned, “Life punishes those who come too late.” The inflexible Honecker did not heed Gorbachev’s remarks. Faced with growing protests for reforms such as those in the USSR and having lost the favor of Gorbachev, Honecker was forced to resign two weeks after the Soviet Premier’s visit. With Honecker’s resignation the world became aware of East Germany’s fragile and overextended economic state.

July 11, 1989

U.S. President George H. W. Bush And Secretary Of State James Baker Honored

Hungarian Premier Miklos Nemeth presents U.S. President George H. W. Bush (left) and Secretary of State James Baker (right) with inscribed plaques containing a section of barbed wire removed from the Hungarian-Austrian border.

October 4, 1989

German Police Guard the U.S. Embassy to East Berlin

A long line of East German police guard the U.S. Embassy to East Berlin, October 4, 1989, to prevent more East Germans from entering the building. Eighteen East Germans had fled there in search of freedom in the West in the previous five days.

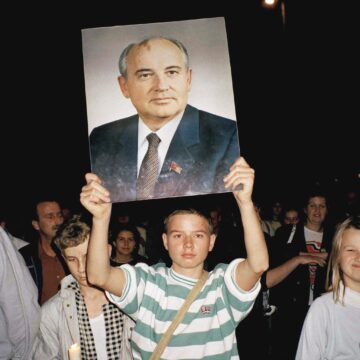

Soviet Reforms Spring Hope

Many in East Germany, like this young man here carrying the photo of Mikhail Gorbachev in 1989, sought hope in the Soviet leader’s reforms. U.S. diplomat G. Jonathan Greenwald, posted in East Berlin from 1987 to 1990, remembers in this interview clip the anticipation of change around him in the months before the Wall fell.

A Gap in Leadership

Although this photo shows apparent cheer between Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev, left, and East German General Secretary Erich Honecker, the two held divergent views on the future goals of communism.

U.S. diplomat G. Jonathan Greenwald, East Berlin, observed the lack of leadership that contributed to East Germany’s collapse. In this audio clip, G. Jonathan Greenwald, Political Counselor to East Berlin (1987-1990) reflects on conditions that led to the fall of East Germany.

Agents of Change

For decades the Protestant church movement had been the political conscience of East Germany, but by September 1989 diplomat G. Jonathan Greenwald observed it coalescing into a political movement. Monday night services in Leipzig grew into Monday demonstrations, expanding to more than 100,000 protesters, pressuring a sickly Honecker to resign. Before the Wall’s demise on November 9, Leipzig protesters numbered 500,000. On November 4, an estimated 1,000,000 demonstrated in East Berlin, almost anticipating the momentous change to come just five days later.

The Church Leads Social Protests

This photo presents the 1981 consecration of an Evangelical church in East Germany. In the audio clip, U.S. diplomat G. Jonathan Greenwald, East Berlin, stressed the leadership of the church in organizing East German social protests.

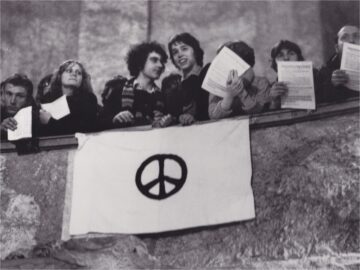

Seeking Peace and Reform

Students appear here at a 1982 Peace Forum in Dresden, East Germany, displaying a universally recognized sign for peace.

In this audio clip, Richard C. Barkley, U.S. Ambassador to East Germany from 1988-1990, speaks about the desire of some East German students and church members for reforms similar to those in the USSR and the government’s response.

1989

November 9

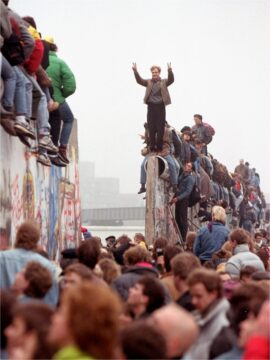

When East Berlin police withdrew at the Wall that night, diplomacy helped secure people’s safety. West Berlin’s mayor, Walter Momper, fearing a stampede, contacted Harold Gilmore, the U.S. Minister to West Berlin. For several years, the United States shared its diplomatic presence in West Berlin with allies Britain and France on a monthly rotation. November, 1989 had been the United States’ turn and Gilmore had only been at his post a little over a week when the news came of massive crowds pouring across the Wall from East to West.. Making a command decision, Gilmore mobilized West Berlin police immediately instead of following a lengthy command chain with potentially fatal consequences, sensibly enabling West Berlin police to direct the throngs.

Despite the Wall’s brutal history of death and repression, that night no one fired shots or turned loose the dogs. Berliners flocked to the Wall in the dark, and in days ahead amazed and awed that this dreadful symbol of repression was crumbling. Peacefully gathered celebrants danced and played music, chipped at the hated concrete or scaled to the top, raising their arms in victory.

1989

Climbing the Wall

A man atop the Wall raises his arms in triumph in 1989 as people below surge through a breach in the barricade. U.S. Ambassador Richard Barkley to East Germany, describes the disbelief and amazement of many in the crowd of being able to cross without restrictions from one side of the Wall to the other in this audio clip.

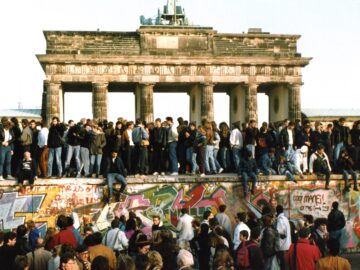

1989

The Immediate Opening of Doors

People lined the top of the Wall in 1989 with the Brandenburg Gate in the background as a crowd gathered below. U.S. Ambassador Richard Barkley to East Germany, recalls in the audio clip how people responded to the startling news that they could freely cross the Wall.

1989

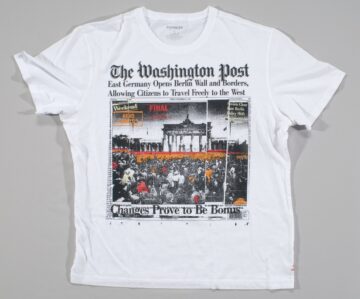

T-Shirt, November 10, 1989, Washington Post Front Page

T-shirt with a screened image of an artistic rendering of the front page of the Washington Post’s November 10, 1989 edition. Excitement over the sudden fall of the Wall fueled demand for commemorative items.

The Economy Grows

On November 18, 1989, the Kurfuerstendamm Boulevard, the main shopping thoroughfare in West Berlin, was crowded with people as hundreds of thousands came over from East Germany for shopping and sightseeing.

George Ward, the Deputy Chief of Mission to West Germany from 1989-1992, describes in this interview clip how the effects of a market economy began to appear in East Germany.

1989

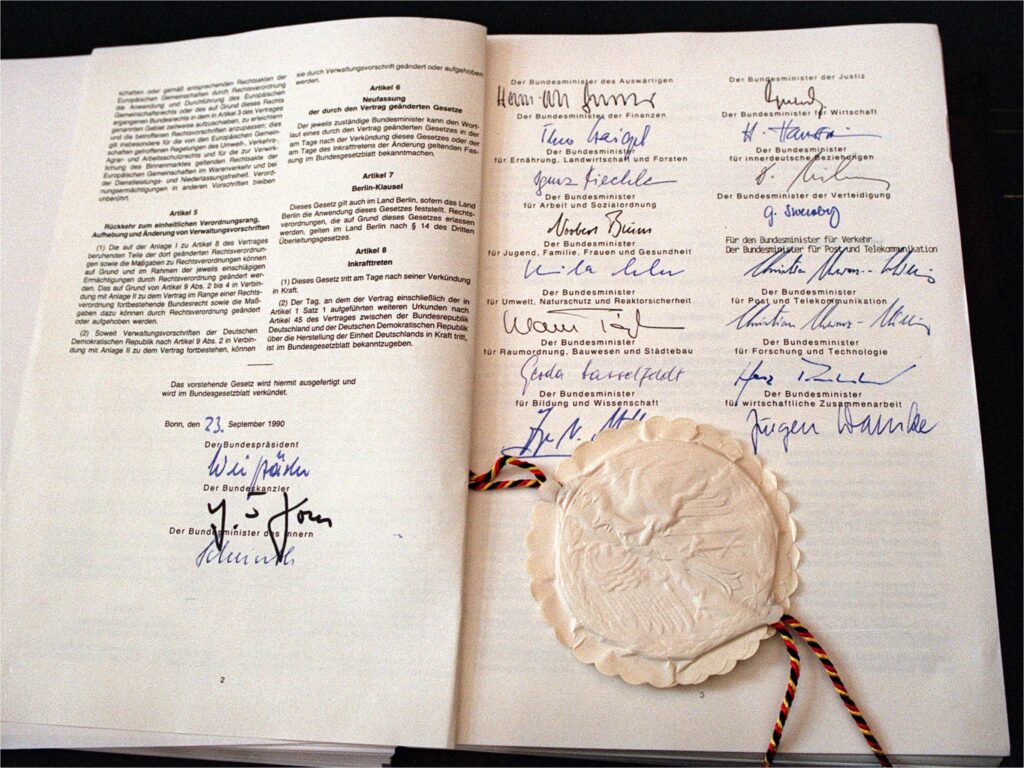

Germany: East and West Unite

Throughout the Cold War, many Germans, East and West, kept hope alive for national unification. President George H.W. Bush and Secretary of State James Baker III endorsed West Germany’s Chancellor Helmut Kohl’s 1989 proposal seeking unity, despite resistance from Britain and France. U.S. and German diplomats worked collegially together on the Two Plus Four Agreement – Two Germanys and Four Allies, finally bringing an end to conflict that emerged in post-War Germany. On August 31, 1990, two Germanys signed a Unification Treaty and on October 1, 1990, the Allies suspended rights to Germany. On October 3, East and West Germany joined together. A new national holiday was born.

–

1989

The Turning Point

“Die Wende” (or “The Turning Point” in German) was a phrase Germans used to describe the period of time between the Wall coming down and reunification in 1990. The turning point was not only a change in political dialogue advancing towards a unified Germany, but civic participation in achieving that goal. The turning point began in 1989 before the Wall came down, as thousands gathered to protest human rights violations under communism, and thousands fled Soviet-controlled Eastern bloc countries. These events caused a “turn” within East Germany as democratic elections were held and those leaders entered into diplomatic negotiations to reunite the nation. Die Wende was the political and civil process, which led to the ultimate goal of a unified democratic Germany.

Building a Unified Germany

East Germans atop the Berlin Wall in 1989 display the sign in English, “COME TOGETHER.” The Consul General to Munich, David Fischer. describes in the audio clip how U.S. Ambassador Vernon Walters stationed in Bonn, recognized the importance of German longing for national unity.

2000s

“We Did Believe”

U.S. diplomats, following the lead of President George H. W. Bush and Secretary James Baker III, believed in supporting German unification. New evidence, however, reveals that Britain’s Margaret Thatcher secretly visited Gorbachev and France’s Mitterrand, stating, “We do not want a united Germany.” A primary U.S. concern of German unity, according to diplomat Geoffrey Chapman, was Germany opting out of NATO. In the end, after determined negotiations, Germany remained in NATO.

Robert Zoellick, Counselor under Secretary of State James Baker, III, played a leading role in conducting the Two Plus Four Agreement negotiations for the United States. Other countries participating were East Germany, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union.

December 12, 1989

The Diplomacy of Baker, Bush, and Gorbachev

Secretary of State James Baker met with German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, to discuss the next steps toward German unity.

Margaret Tutwiler, who served as the U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs from 1989 to 1992, explains in the interview clip her view on the understated reaction to historic events in Germany by U.S. officials and the diplomatic skills of Baker, Bush, and Gorbachev.

1989

Discussing the Future of Berlin

The four Allied ambassadors to West Germany in Berlin convened in 1989 at the Allied Control Council Headquarters (Kommandatura) to discuss the city’s future. From left to right are: Vernon Walters (U.S.), Sir Christopher Mallaby (Great Britain), Wjatsheslav Kotshemassov (Soviet Union), and Serge Boidevais (France).

J.D. Bindenagel, who served as the Deputy Chief of Mission to East Germany from 1989 to 1990, recalls the strong West German reaction to their meeting in the audio clip.

March 14, 1990

Two Plus Four Delegates

The delegation for the first Two Plus Four negotiations poses for the press in Bonn, West Germany. From right to left: Dieter Kastrup (West Germany), John Weston (Great Britain), Anatoli Leonidovich Adamachin (USSR), Bertrand Dururcq (France), Hans-Dietrich Genscher (West Germany), Ernst Krabatsch (East Germany) and Robert Zoellick (USA).

AP photo

August 3, 1990

Signing Of The German Unification Treaty

West German Secretary of State Wolfgang Schaeuble (left), his East German counterpart Guenther Krause (right) and East German Prime Minister Lothar de Maizière (center) symbolically holding hands following the signing of the German unification treaty in East Berlin.

AP photo

1987-1990

Moving Toward Unification

Foreign ministers signing the Two Plus Four Treaty in 1990 celebrate the move toward German unification. Pictured are Roland Dumas (France), Eduard Shevardnadze (Soviet Union), James Baker III (U.S.), Hans-Dieter Genscher (West Germany), Lothar de Maizière (East Germany) and Douglas Hurd (Great Britain) with Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, center.

G. Jonathan Greenwald, who served as a political counselor in East Berlin, clarified the United State’s stance on German reunification, as well as the significance of the treaty’s title.

1990

New Era, New Embassy

In 1990, two U.S. embassies and the Berlin mission consolidated into one diplomatic post. The new U.S. Embassy compound in Berlin, opened in 2008, was built near the historic Brandenburg Gate on the site of the previous embassy (destroyed during WWII). Released secret police (Stasi) files revealed that spies operating in both East and West Berlin focused on U.S. diplomats. In the transition period, U.S. Ambassador Richard C. Barkley made sure that Checkpoint Charlie, the U.S. crossing point in a divided Berlin, moved to a fitting new home as a museum, “to make sure that it is not portrayed in a humiliating way for the Russians.”

1980-1989

U.S. Minister’s Flag, Berlin

This flag represents the diplomatic position of the U.S. Minister to Berlin. It was presented as a gift to Ambassador Harry J. Gilmore, the last person to serve in the position, when the mission was abolished in 1991. The plaque that accompanied it, complimenting Gilmore’s service during a period of great change, reads “America Saved Its Best For Last.”

FROM THE COLLECTION

Order of Merit of Berlin

1998

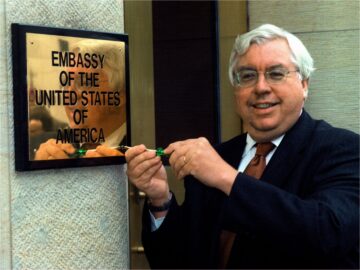

Closing the East Berlin Embassy

After the U.S. Embassy East Berlin closed in 1990, Bonn was the site of the only remaining U.S. embassy in Germany. In 1998, the U.S. Embassy moved again, from Bonn back to Berlin. In this 1998 photo, U.S. Ambassador John Kornblum prepares the new Berlin embassy sign.

Harold Geisel, who served as the Counselor for Administration in Bonn, Germany, from 1988 to 1992, describes in the audio clip how the State Department administratively handled closing the U.S. Embassy in East Berlin in 1990.

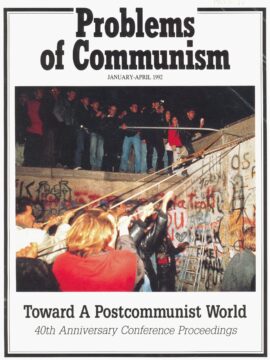

1992

Problems Of Communism: Toward A Postcommunist World

The U.S. Information Agency published Problems of Communism, a bimonthly journal, during the Cold War. “Toward a Post-Communist World” was the subject of a 1992 conference marking the journal’s 40 years in print. The journal continues today with a different publisher under the name Problems of Post-Communism, keeping in step with the new era now that the “Iron Curtain” has fallen.

U.S. Department of State, Bureau of International Information Programs

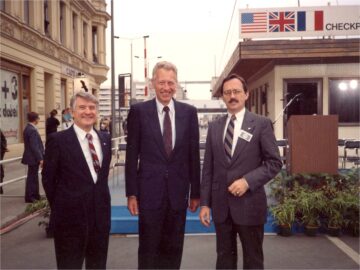

1990

Checkpoint Charlie Decommissioning Ceremony

Attending the Decommissioning of Checkpoint Charlie, Berlin, were the U.S. Minister to West Berlin Harry Gilmore (left); U.S. Minister to East Berlin, J.D. Bindenagel (right), and West German Political Director Dieter Kastrup (center).

Courtesy of J.D. Bindenagel

Lasting Effects of Freedom

Years after unification, Germans continued to bridge the psychological and economic divide between East and West, assisted by billions in financial assistance to aid former East Germany into complete economic and social integration. Growing business ventures in former East Germany and the region’s resurging economy also helped close economic disparity. U.S. diplomats maintain close relations with a united Germany, and the nation is one of the United States’ strongest European allies.

1990

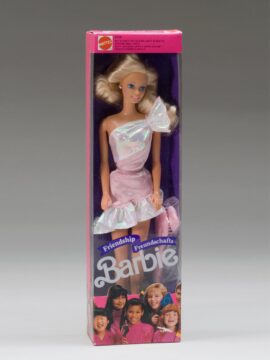

“Friendship Barbie” Doll

It is not known if “Friendship Barbie” celebrated the collapse of the Wall with her friend “Summit Diplomat Barbie,” but both dolls made a popular culture statement in 1990 about the end of the Cold War. “Friendship Barbie” was sold only in Berlin and East Germany. The words on the back of the box read, “Barbie welcomes friends from all over the world.”

2004

Berlin Wall Underfoot

A passerby in Berlin crosses a memorial strip near the Brandenburg Gate where the Wall once stood.

AP photo

c. 2000

Commemorative Fragments of the Berlin Wall

In May 2009, three members of Berlin’s Staatskapelle Orchestra brought these acrylic-encased fragments of the Wall with them on a trip to New York City. The orchestra was performing at a Mahler Festival at Carnegie Hall, and the members brought these tiny souvenirs as tokens to give away. Twenty years after the Wall’s fall, it endured as a symbol of Germany and what it had overcome. Inscribed, “A Piece of German History,” these fragments also include “The Wall” written in German, English, French, Spanish, and Italian.

Gift of Matthias Glander, Felix Schwartz, and Wolfgang Kühnl.

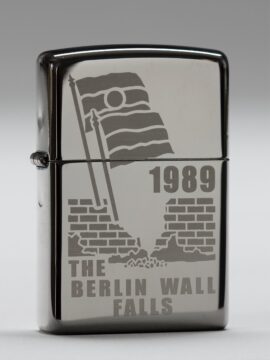

1989

Zippo Cigarette Lighter

This silver Zippo lighter is etched with an outline of the broken Berlin Wall and two German flags celebrating unity. The symbolism commemorates Germany’s historic events and transforms an ordinary lighter into a popular culture souvenir of a historic period.

1989-today

The Legacy of the Berlin Wall

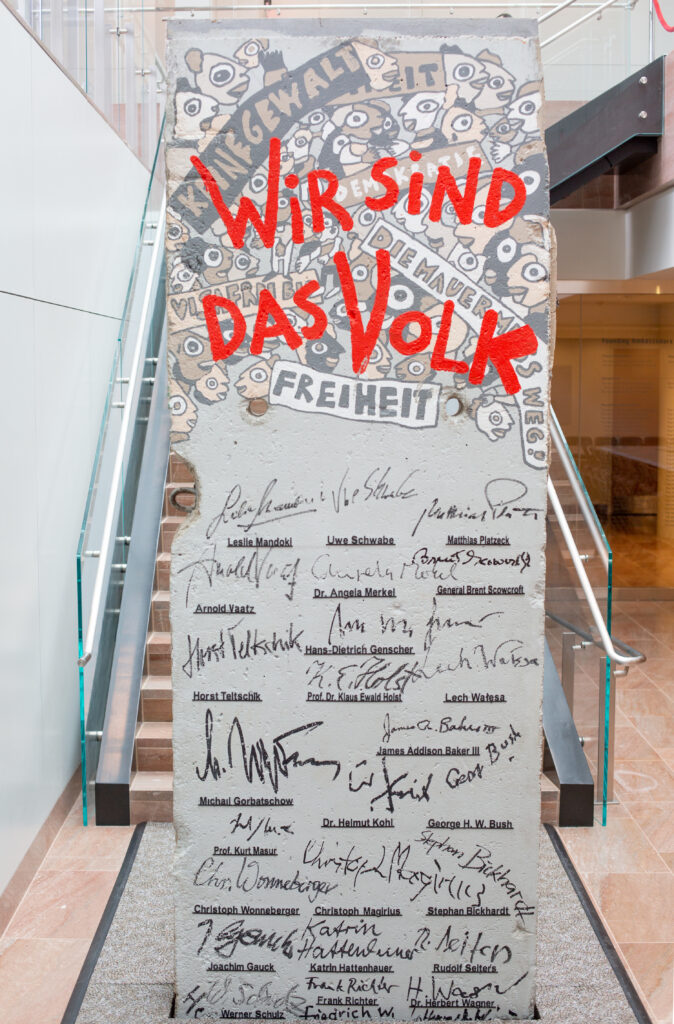

Decades after its fall, the Berlin Wall remains one of the most well-known physical examples of the Cold War, and the fear, repression, division, and isolation that era represented. Preserved segments of the Wall now represent a much different—and positive—global message, that of the strength and power of diplomacy and the courage of ordinary people to effect lasting change.

While many segments of the Berlin Wall can be seen around the world, there is only one Signature Segment, and it is permanently on display at the National Museum of American Diplomacy at the U.S. Department of State in Washington, DC.

–

The Signature Segment

The 13-foot-high, nearly three-ton piece of the Berlin Wall on display in the National Museum of American Diplomacy is known as the “Signature Segment” for its unique collection of signatures by activists, diplomats, and political leaders who fought to end communist rule in eastern Europe.

Among the 27 signers were German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, U.S. President George H.W. Bush, and Premier of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev, known as the “Fathers of German Unity.”

2009

Painting the Segment

Michael Fischer-Art, a German artist, painted graffiti art on the Signature Segment in 2009 to mark the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. During the Cold War, Fischer-Art lived in Leipzig, East Germany and was arrested several times for taking part in pro-democracy protests. He created many of the original banners used during the protests.

2009

“We Are the People”

The words painted on the Signature Segment were inspired by banners carried by protesters during Leipzig’s “Peaceful Revolution” in 1988–89:

Die Mauer muss weg: The wall must go

Keine Gewalt: No violence

Demokratie jetzt: Democracy now

Freiheit: Freedom

Freie wahlen: Free voters

Wir sind das Volk: We are the people

Stasi in den Tagebau: Send the secret police to hard labor in the deep mines

Visafrei bis Hawaii: Visa-free to Hawaii

2015

Bringing the Wall to the National Museum of American Diplomacy

On October 7, 2015, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry formally accepted the “Signature Segment” on behalf of the U.S. Department of State from German President Joachim Gauck, one of the original signers. The leaders are pictured here shaking hands in front of the segment at the National Museum of American Diplomacy.

Below is the full list of those who signed the segment:

James A. Baker III, 61st U.S. Secretary of State (1989–1992)

Stephan Bickhardt, Theologian and civil rights activist

George H.W. Bush, 41st President of the United States (1989–1993)

Dr. Heino Falcke, Theologian

President Joachim Gauck, President of the Federal Republic of Germany (2012-2017)

Hans-Dietrich Genscher, Federal Minister of Foreign Affairs, Federal Republic of Germany (1974-1992)

Mikhail Gorbachev, President of the Soviet Union (1990-1991)

Katrin Hattenhauer, Activist

Dr. Klaus-Ewald Holst, Chairman, Leipziger Verbundnetz AG (VNG) (1990-2010)

Helmut Kohl, First Chancellor of reunified Germany (1990-1998)

Christoph Magirius, Pastor

Lothar de Maizière, German Federal Minister for Special Affairs (1990)

Leslie Mándoki, Musician

Kurt Masur, Conductor

Chancellor Angela Merkel, Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany (2005-2021)

Matthias Platzeck, Minister-President of Brandenburg (2002-2013)

Frank Richter, Pastor

Friedrich Schorlemmer, Theologian

Werner Schulz, Former Member of the Bundestag (1990-1998, 2009-2014)

Uwe Schwabe, Civil rights activist

Brent Scowcroft, U.S. National Security Advisor (1975-1977; 1989-1993)

Rudolf Seiters, German Federal Minister for Special Affairs (1989-1991)

Horst M. Teltschik, Deputy Head of the Federal Chancellery (1983-1989)

Arnold Vaatz, Mathematician and Politician

Dr. Herbert Wagner, Mayor of Dresden (1990-2001)

Lech Wałęsa, President of Poland (1990-1995)

Christoph Wonneberger, Pastor

Disclaimer: The audio clips in this online exhibit were read aloud by actors.

BEYOND THE WALL

Explore More of the Berlin Wall

Activity

Voices of the Berlin Wall: Analyzing Oral Histories

In this activity, students will analyze oral histories and see how they support, contradict, or add to their current understanding of the Berlin Wall.

Lesson Plan

The Diplomat’s Dilemma: Diplomacy Beyond the Berlin Wall

In this lesson, students will develop cultural diplomacy strategies to engage with people living on the other side of the Berlin Wall, understanding the vital role of diplomacy in overcoming barriers.

Video

Diplomacy Classroom: 2+4 = Unity: The 30th Anniversary of German Reunification

In honor of the 30th anniversary of German reunification, in this Diplomacy Classroom, we looked back at the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect…

Story of Diplomacy

What Are the Helsinki Accords?

On August 1, 1975, the Helsinki Accords, also known as the Helsinki Final Act, were signed. The signing of the Helsinki Accords was a big…

Collection Highlights

The “Signature Segment” of the Berlin Wall

From 1961 to 1989, the Berlin Wall served both as a physical barrier as well as a symbol of division and repression. Families, friends, and…