Constance Harvey, the Medal of Freedom, and the Bravery of a Diplomat in World War II

Being a diplomat can mean putting yourself at risk, especially in times of violence or war. Diplomats may help evacuate their nation’s citizens from dangerous situations or stay in contact with political factions or groups to help understand a changing political situation.

Constance Ray Harvey, one of the first women to become a Foreign Service Officer, voluntarily put herself in danger while serving as a diplomat in France during World War II. For her extraordinary efforts, she earned the Medal of Freedom—the predecessor of today’s Presidential Medal of Freedom.

The National Museum of American Diplomacy recently added Constance Harvey’s Medal of Freedom to its permanent collection. The museum’s collection already included other personal items, such as military dog tags she wore while serving in Europe and her Phi Beta Kappa pin.

What exactly did Constance Harvey do to earn the Medal of Freedom?

FROM THE COLLECTION

Constance Harvey's Medal of Freedom

A New Post in Vichy France

In January 1941, the U.S. Department of State transferred Constance Harvey from Bern, Switzerland, to the U.S. Consulate in Lyon, France, to serve as a Vice Consul.

France had fallen under German Nazi control in June 1940, but under the terms of the armistice, there were two zones: one under German military occupation, and one that was nominally a free French state. This became known as Vichy France, and Lyon was within its boundaries.

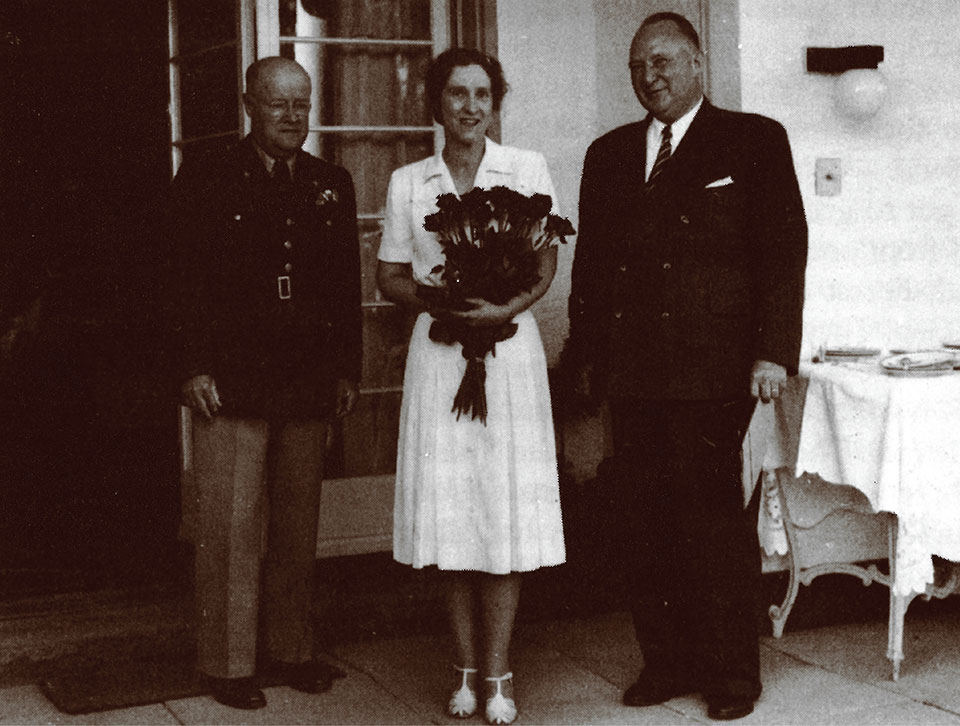

From the start of her time in Lyon, Harvey stayed in touch with General Barnwell Legge, the U.S. military attaché still stationed in Bern. She had developed a strong friendship with Legge and his wife.

General Legge didn’t waste any time asking Harvey for her help. From her convenient location in Lyon, and by virtue of her official position, she would prove useful to the war effort in maintaining contacts, gathering information, and even doing a bit of smuggling—all in the name of the broader Allied cause against Germany and the Axis powers.

“Up to Some Monkey Business”

Constance Harvey did not hesitate to respond to General Legge’s request with an enthusiastic “yes.” As she recalled in her 1988 oral history, “I got into a whole lot of business for our military attaché in Bern, which did not go through the embassy at Vichy.”

This “business” varied, according to Harvey’s recollections, but was in support of General Legge’s efforts to convey useful information about the war raging in Europe, from his post in neutral Switzerland to the War Department in Washington, D.C.

In Lyon, Harvey maintained important personal contacts in the northern part of France, which was in the zone occupied by the German military. Her role as a Vice Consul gave her access to the official diplomatic correspondence pouches, and she used them to covertly send information to Bern—sometimes sent by a courier, sometimes carried by herself—where General Legge would receive it.

When she carried the pouch herself, traveling the 200 miles between Lyon and Bern, she sometimes met General Legge in Geneva, just across the French border and about halfway between Lyon and Bern.

On one of those occasions, she delivered a copy of a plan which showed all of the German anti-aircraft stations around Paris—an extremely valuable piece of information. As she remembered, “he turned kind of pale and said, ‘I’ll remember this!'”

Reflecting in her oral history on being presented the Medal of Freedom in 1947, Harvey seemingly minimized the importance of her role, remarking: “Quite a few people were [given the Medal of Freedom] who had been up to some monkey business — just to help out.”

“I know all about you kids, what you’ve been up to.”

When Constance Harvey began helping General Legge in January 1941, the United States was officially a neutral country. It would not be until the attack on Pearl Harbor of December 7, 1941, that the country would enter the war.

However, the United States had begun to shift from a position of neutrality to non-belligerency. As early as 1940, the United States began providing some forms of aid to the Allied nations in their struggle against Nazi Germany and the Axis powers.

Harvey’s assistance to General Legge took place for nearly a year as an independent enterprise without the knowledge of her superiors. That changed shortly after the U.S. declaration of war.

In her oral history, Harvey remembered being summoned with a colleague to their boss’s office, the recently-arrived Consul General in Lyon. “I know all about you kids, what you’ve been up to,” she remembered him telling them. “You can take me aboard now. We can share it together. I was told what you were doing.”

FROM THE COLLECTION

Constance Harvey’s Dog Tags

Gestapo at the Border

When Harvey made the journey to General Legge in Switzerland, she would encounter Vichy French officials—and German Gestapo officers—at the border. Despite this, she managed to avoid being caught. “I learned all the tricks. Everybody had to,” she recalled in her oral history.

One of those tricks involved using a quirk of the car she drove, a Ford. The car’s glove box, unlike other cars she had driven, had a separate key used only for the glove box.

“… When I got out to show my papers to the [customers officer], I would leave my keys conspicuously dangling in the ignition,” Harvey explained. “The other key [for the glove box] was down here around my neck under my dress.”

With the special glove box key safely hidden and the car’s other keys left easily accessible in the ignition, the glove box worked to hide her contraband. “And I would go in [to talk to the customs officers] … and soared right through.”

Asked by the oral history interviewer whether she was frightened during her encounters with the Gestapo, Harvey said she wasn’t. “You don’t have time,” she answered. “Besides, I was so fascinated; I was so interested, so determined to do it. Of course, I’ve been frightened in my life, but not doing that sort of thing, not a bit.”

Saving a life

One of the more remarkable episodes of Constance Harvey’s time in Lyon came near the end of her time there and illustrates her personal character and resolve.

With the invasion of North Africa by Allied Forces in early November 1942, Germany and the Axis moved to militarily occupy Vichy France, and American diplomatic operations were no longer allowed.

Days before they were to be taken into custody and interned by Vichy authorities, one of Harvey’s colleagues, a Belgian citizen who had worked with her on representing Belgian diplomatic interests, was pulled out of his hospital bed by the Vichy police and put on a train to be taken to a concentration camp.

Harvey was not having it. She recalled telling her boss, “I’ve got to go and see the police. I’m going at once.” He told her there wasn’t anything she could do, but she insisted that she must try.

She spent around two hours arguing with an official at the police station. She told him bluntly,

“I will not go to a comfortable, diplomatic internment and let that man go to a concentration camp. I won’t take it.”

– Constance Harvey

She refused to leave until he did something, but he was not budging either. Finally, having been moved to tears by fury and frustration, she gave him an ultimatum:

“I said, ‘Look here. I went to school in France. France is a second country to me. If you don’t get this man back to the hospital so that he can have the operation which he’s scheduled to have, I’ll spend the rest of my life working against France.'”

The official relented, picking up the phone to make a call. Ten minutes before the train to the camp was to leave, Harvey’s Belgian colleague was pulled off and saved. As Harvey recalled, “He never would have lived—he was in bad health as it was—he wouldn’t have possibly survived [a concentration camp].”

Epilogue

In November 1942, Constance Harvey and her colleagues in Lyon were interned by the Vichy authorities and housed in hotels in Lourdes, France. Later, the Germans took them into custody and sent them to the German town of Baden-Baden. They were released in February 1944 and returned to the United States.

On an assignment back in Washington, D.C., Harvey learned that General Legge had earned a reputation in the government for being the best source of information for what was happening on the front lines of Germany’s battle against the Soviet Union. He had developed an effective information network, and as Harvey recalled: “I was part of it.”

Sources:

“1940s–Diplomat and World War II Heroine,” American Foreign Service Association (2014)