Advancing democracy abroad and protecting it at home has long been a pillar of American diplomacy. In the Civil War era, Americans from all walks of life discussed domestic politics and foreign policy. Debates on slavery were at the center of international relations.

Many pointed out that American slavery was incompatible with the principles of democracy and damaged America’s relationships with key allies. Other Americans would go to war to preserve slavery. The Confederate States of America sought international recognition, much like the United States did in 1776.

After the war, the diplomatic corps changed. African Americans, including formerly enslaved people, represented the United States in national office and as diplomats abroad. This inclusive expansion of democracy faded quickly. At the end of the 19th century, Black diplomats faced intense racism as “free but unequal” became the law of the land.

Slavery and Diplomacy

In the mid-1800s, slavery was at the center of politics. Like today, domestic policy and foreign policy were intertwined, involving citizens and diplomats alike.

How did diplomacy resolve these challenging issues during this turbulent time?

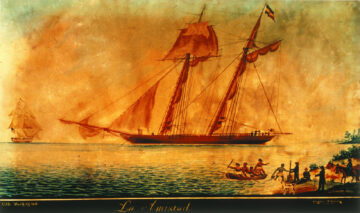

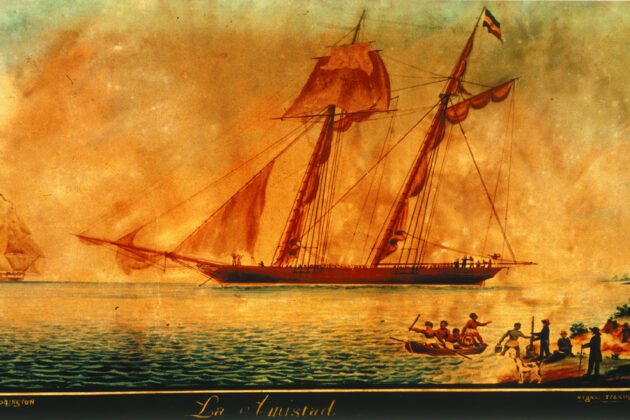

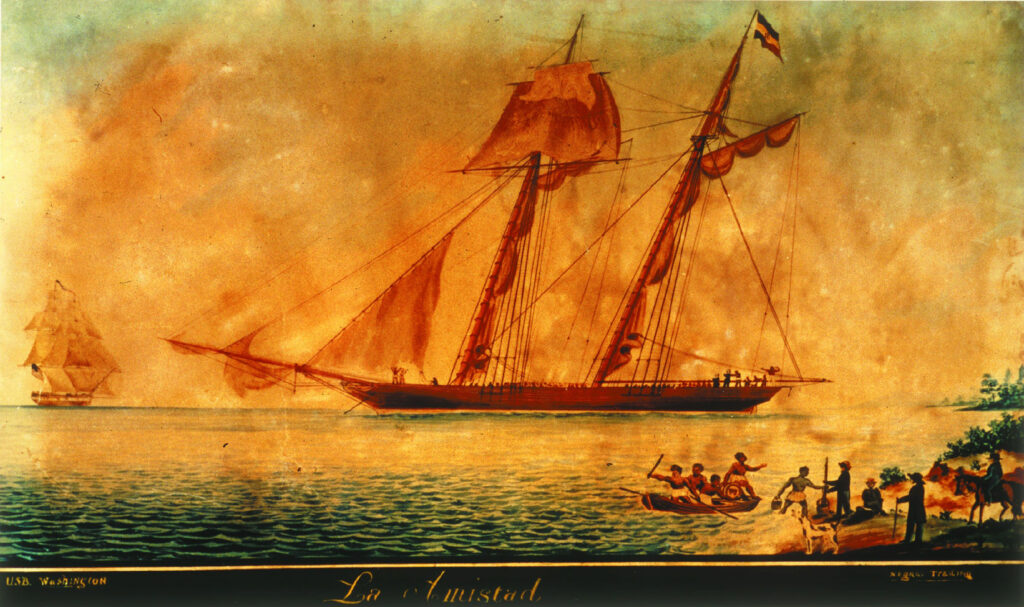

The Amistad

In 1839, European enslavers kidnapped a group of Africans from Sierra Leone. This was in violation of the treaties banning the international slave trade. Sold in Cuba, Spaniards were transporting them aboard the ship La Amistad. The enslaved Africans revolted and intended to sail back to Africa. A few weeks later, the U.S. Navy intercepted the ship and jailed the Africans for piracy.

Spain demanded the Africans be returned as their lawful property. However, American abolitionists argued that the Africans had been illegally enslaved and demanded their release.

Discover how diplomacy ensured that the United States and Spain abided by international agreements.

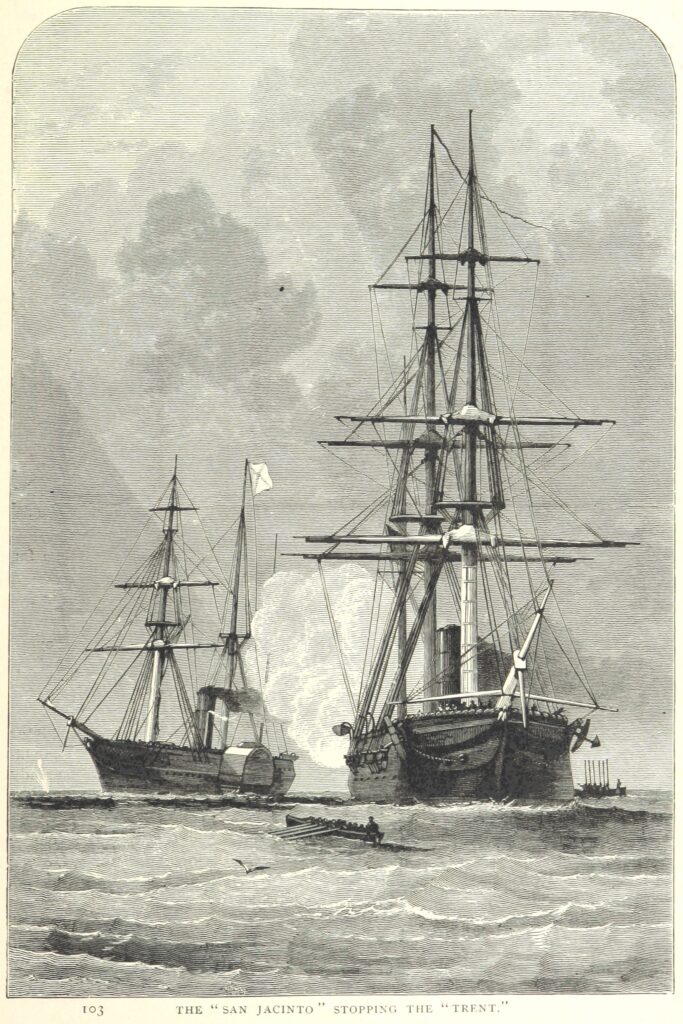

The Trent Affair

Seven months into the Civil War, a diplomatic crisis emerged that threatened war between the United States and Great Britain.

In November 1861, the U.S. Navy captured two Confederate diplomats aboard a British ship, the Trent. The men were on their way to persuade the British government to recognize the Confederate States of America as an independent nation.

The British, who had declared themselves neutral in the Civil War, strongly protested the seizure of the Confederates from their ship.

President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward didn’t understand how Great Britain, a nation that opposed slavery and a U.S. ally, could claim neutrality.

Learn how diplomacy prevented the crisis from escalating.

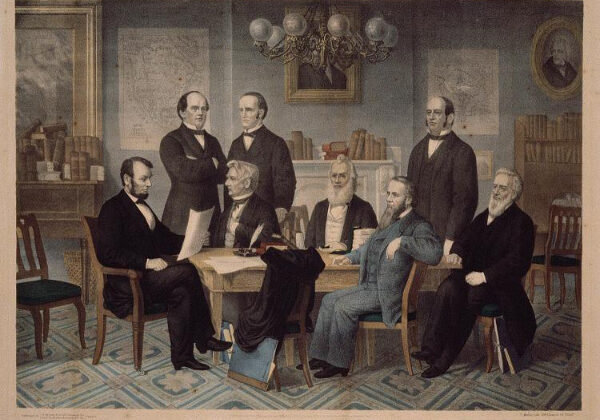

The Emancipation Proclamation

Did you know that the Emancipation Proclamation was also a foreign policy statement?

On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. It declared that all enslaved people in the Confederate states were free. The announcement was also an ultimatum to foreign governments: chose slavery and the Confederacy or liberty and the United States.

Before the start of the Civil War, American abolitionists like Sarah Parker Remond traveled to Great Britain speaking out against the horrors of slavery. Through public speeches, they advocated for the British people to support abolition in the United States.

See how diplomats’ appeals influenced European nations’ recognition of the Confederacy.

FROM THE COLLECTION

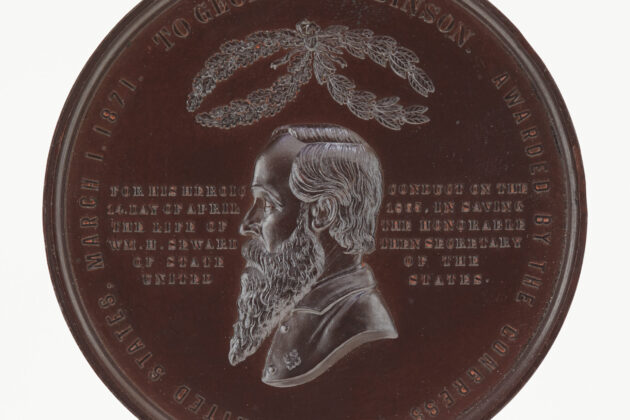

Commemorative Medal

Diplomacy in the Reconstruction Era

During the Civil War, the United States extended full diplomatic recognition to the Black republics of Haiti and Liberia.

In the Reconstruction period following the war, African American men were appointed to positions of power in the government, including at the State Department.

America’s first African American chief of mission was Ebenezer Bassett, who served as U.S. minister to Haiti from 1869 to 1877. During his time in Haiti, Bassett courageously defended refugees and asylum seekers despite opposition from the Haitian government and Secretary of State Hamilton Fish.

The advances that African Americans made during the Reconstruction era diminished in the late 19th century. Oppressive Jim Crow laws enforced racial segregation and denied opportunities for African Americans.

Domestic policies once again influenced foreign policy.

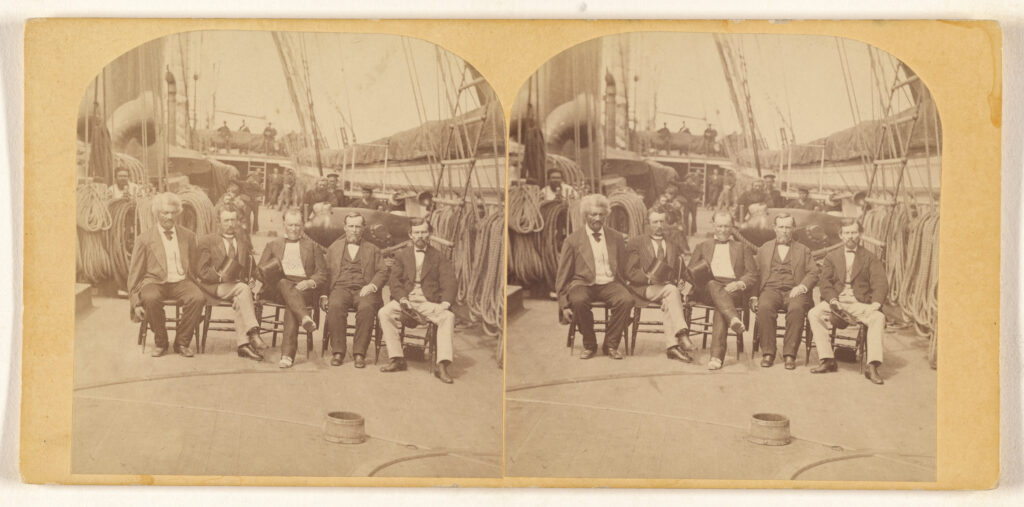

It was during this period that abolitionist Frederick Douglass became the U.S. minister to Haiti. Douglass vowed to work towards the “peace, welfare, and prosperity” of the Haitian people. He quickly won the trust of Haitian president Florvil Hyppolite. But Douglass faced racial discrimination and opposition from white State Department leaders. He resigned in protest in 1891.

Public Program

Diplomacy Classroom: La Amistad and Upholding Democracy

In 1839, the U.S. navy confiscated a Spanish ship, La Amistad, off the coast of Long Island, NY. Aboard were Africans and two Spaniards, who insisted the Africans were their slaves who had taken over the ship, and a treaty between the United States and Spain stated that all “property” be restored. American…

Story of Diplomacy

The Trent Affair: Diplomacy, Britain, and the American Civil War

In 1861, as the Civil War was beginning at home, U.S. diplomats faced a unique dilemma. The United States needed to maintain relationships abroad. At…

Story of Diplomacy

Sarah Parker Remond: Citizen Diplomacy and the Emancipation Proclamation as Foreign Policy

When the Civil War erupted in April of 1861, President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward’s official reason for the war was to…

Story of Diplomacy

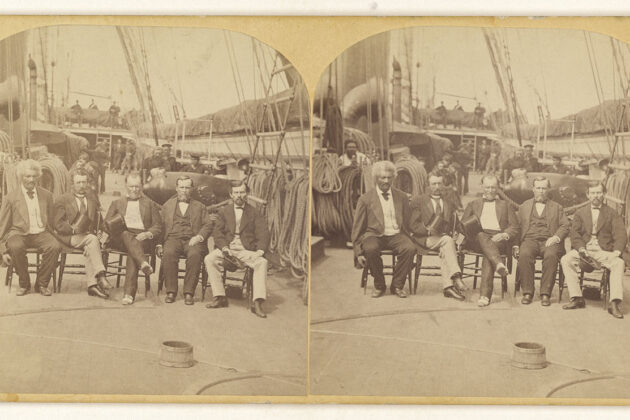

The Diplomatic Career of Frederick Douglass

“One of the duties of a minister in a foreign land is to cultivate good social, as well as civil relations, with the people and…