Simulation

Suez Canal Crisis: National Sovereignty versus International Access to Waterways

On July 26, 1956, Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nassar nationalized the Suez Canal, intending to take control of the canal’s operation and its revenue.

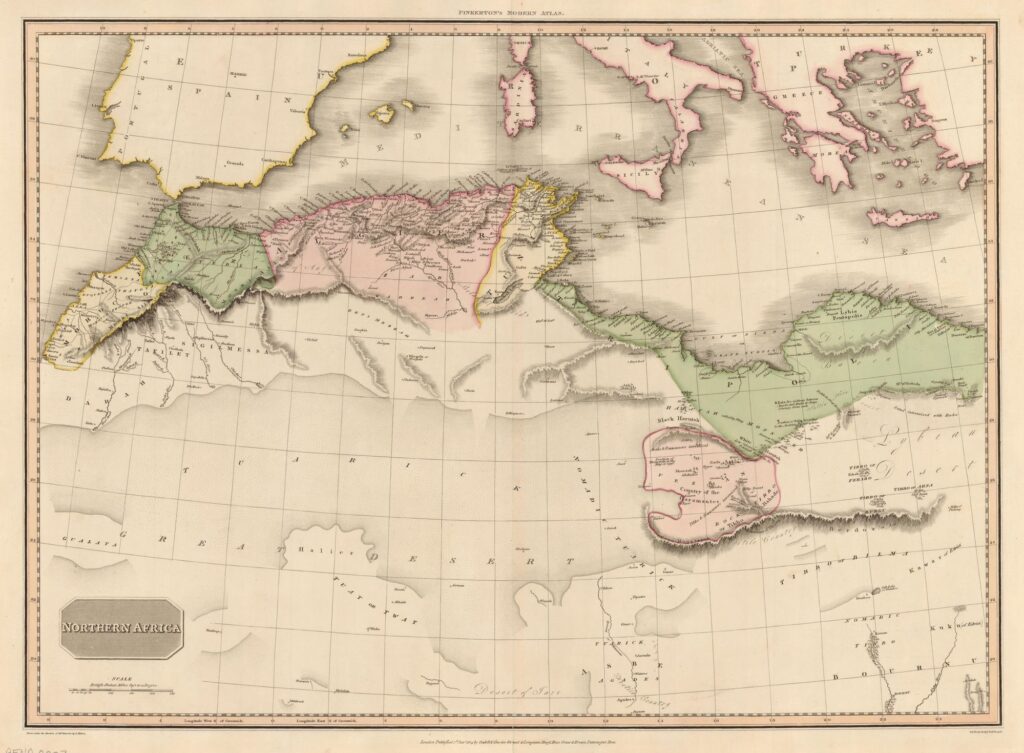

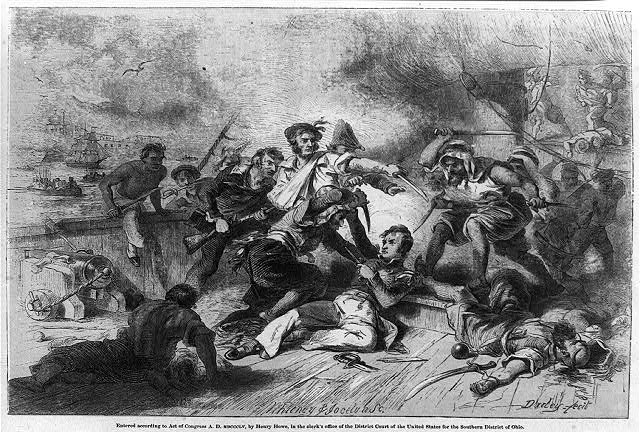

For almost 300 years, leaders of the North African Barbary States hired ship captains to capture foreign ships in the Mediterranean Sea and Atlantic Ocean.

These captains, known as corsairs, kept the ships and cargo, then ransomed the crew or forced them to work in captivity.

This practice was a way for these semi-independent states of the Ottoman Empire to generate money. Some wealthy countries, such as Great Britain, would sign treaties with or make payments to the Barbary States, permitting their merchants to travel the seas freely. These cash payments and preferential trade agreements were called tributes.

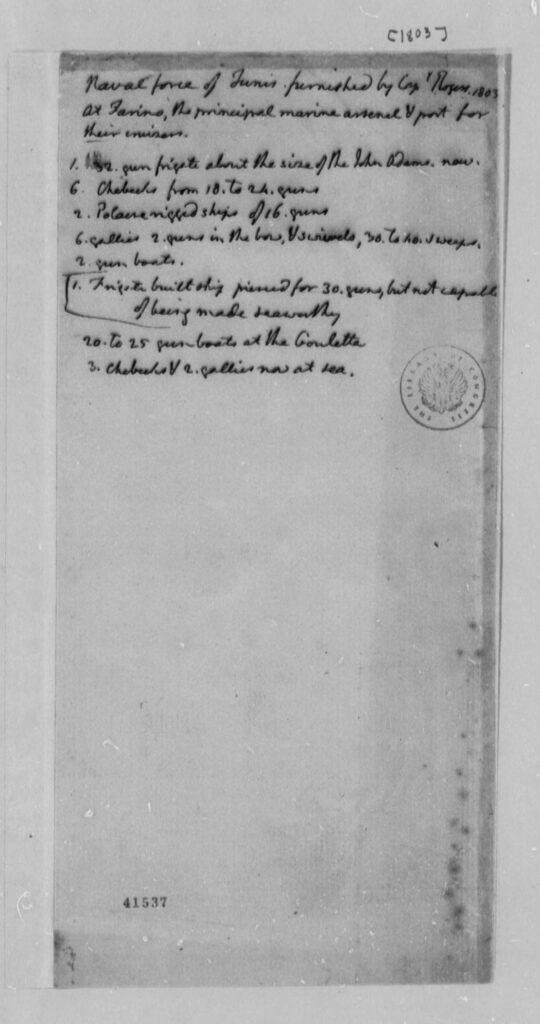

When the United States gained its independence in 1783, it lost the protection of the British navy, and Barbary corsairs captured two American ships in 1785. As a new nation with limited revenue to support its government, the United States had limited funds to pay tribute and many Americans opposed it on principle. In 1793, Algerine corsairs captured 11 more American ships and 100 citizens, prompting a commercial and humanitarian crisis that could not be ignored.

With no navy or substantial annual revenue, how could the United States pay hefty ransom fees and prevent this from happening again?

Would the Barbary States even agree to negotiate terms when they clearly had the upper hand?

After the United States won the Revolutionary War against Great Britain in 1783, it continued to govern the country under the 1776 Articles of Confederation. The Articles, however, proved to be an ineffective document, as Congress had no power to tax or regulate trade.

In 1788, the states ratified the United States Constitution in response to these weaknesses, but national disputes about the role of government and its power continued.

Under the Articles of Confederation, the U.S. Department of State was known as the Department of Foreign Affairs. John Jay, Secretary for Foreign Affairs when the 1785 ship captures occurred, expressed frustration with the Articles’ limitations, complaining that:

They [Congress] may make war, but are not empowered to raise men or money to carry it on. They may make peace, but are without power to see the terms of it imposed. . . . They may make alliances, but [are] without ability to comply with the stipulations on their part. They may enter into treaties of commerce, but [are] without power to enforce them at home or abroad.

One American sailor, James Leander Cathcart, was captured in 1785 and held in Algiers for eleven years. He gained his freedom soon after the United States transitioned from the Articles of Confederation to the Constitution, which provided the U.S. Department of State stronger tools to shape and implement foreign policy. For example, Congress had the power under the Constitution to levy taxes for revenue and to build and maintain a navy.

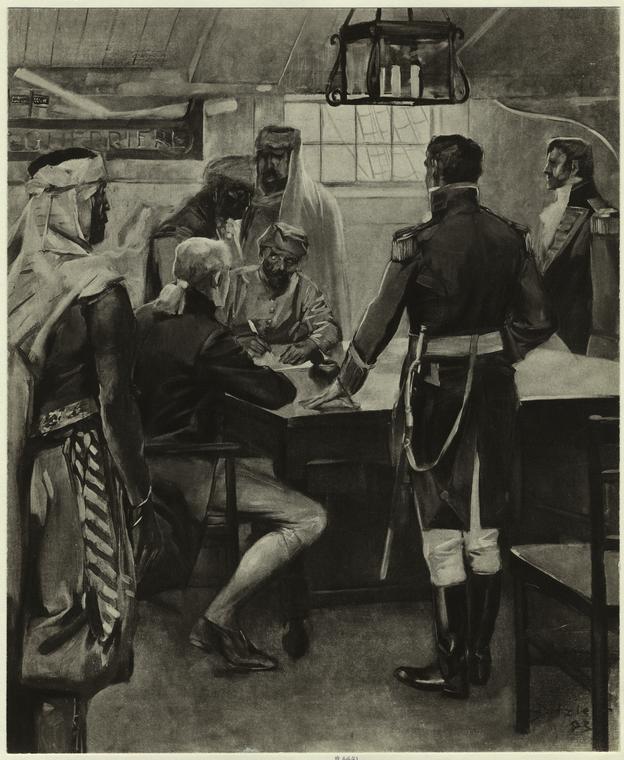

Thomas Jefferson served as the first Secretary of State from 1790 to 1793 under President George Washington’s administration and began negotiations to free the captives and negotiate trade treaties with the Barbary States. These diplomatic talks culminated in treaties under Washington and President John Adams’ administration (1797-1801) and some of the freed captives, like James Leander Cathcart, returned to the Barbary States as United States consuls. The threat to American commerce continued, however, resulting in armed conflict and new treaties more favorable to the United States.

Please find below a playlist of short videos from experts in the field to aid discussion and exploration of the topic.