John Limbert: Bringing Meaning to a “Bunch of Old Clothes”

Think of a historic event you personally witnessed or experienced firsthand. Do you remember what you wore?

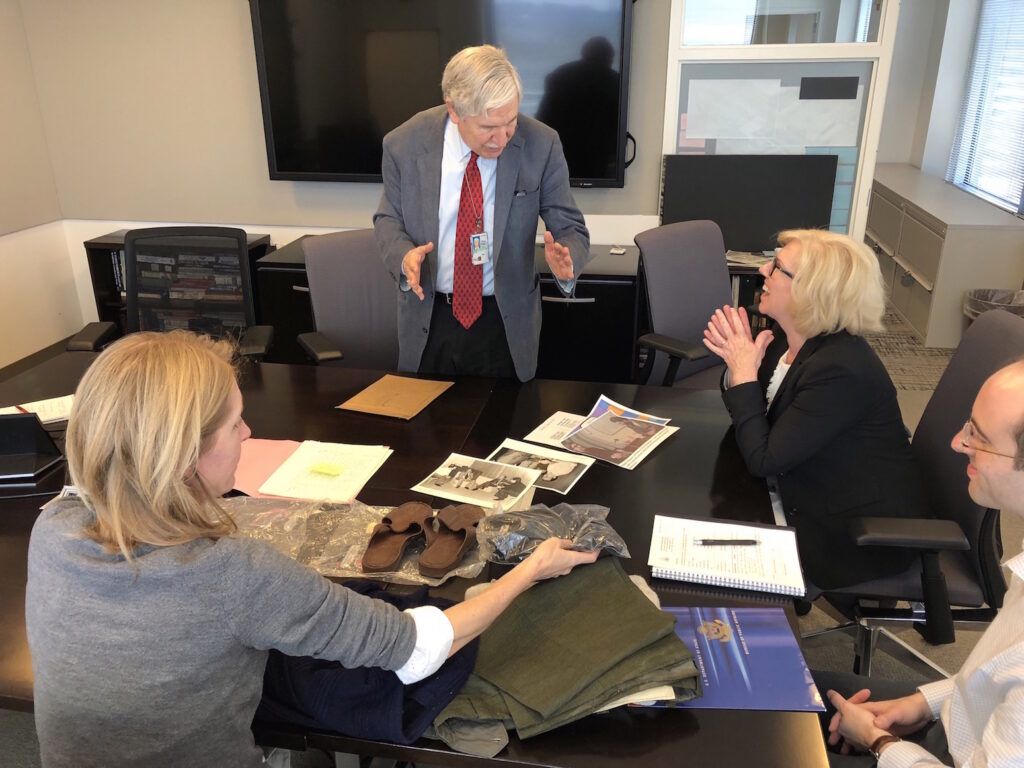

The National Museum of American Diplomacy (NMAD) has several articles of clothing in its collection belonging to diplomats who served on the front lines. The museum intends to interpret several of these items in its permanent exhibit, “The Challenging and Dangerous Work of Diplomacy,” within the context of a significant event in diplomatic history and the personal stories behind the diplomats who wore them. In the exhibit, visitors will be introduced to diplomats, embassy staff, and foreign service nationals who carry out their duties in service to our nation, often in high-risk situations. Retired Foreign Service Officer John Limbert, an American diplomat who was held hostage in Iran, generously made one such donation of historically significant clothing to NMAD.

Being Held Hostage During the Iran Hostage Crisis

Limbert arrived at the U.S. embassy in Tehran in August 1979. Less than three months later, on November 4, Iranian student militants scaled the compound’s walls, seized control of the embassy, and forcibly detained American staff. The Iranians held Limbert and 51 other Americans hostage for 444 days.

Denied any of their personal belongings, the hostages were forced to wear the same clothes they were wearing at the time of the take-over for the duration of their captivity. Limbert, dressed in business casual attire, was wearing dark green wool trousers, a black cotton/wool blend shirt, and a blue wool blend cardigan. To prevent escape attempts, his captors took his shoes and gave him a mismatched pair of brown rubber sandals instead. The left sandal is size 11, and the right sandal is size 8.

Despite the hardships of captivity, Limbert remained optimistic without bitterness toward the Iranians, noting “I maintained professionalism throughout the ordeal. I never became an abuser in return. I used what I knew about Iranian social norms, courtesies, and culture to find a way to work with my captors.” When they told him, “You never stopped being a diplomat” they meant it as an insult. Limbert accepted it as a compliment.

John Limbert generously donated his clothing from his ordeal to NMAD, remarking, “let me thank…the museum of diplomacy for bringing meaning to what would otherwise be a collection of old clothes.”

For museums and their visitors, an object — also known as an artifact — can be important for different reasons. For art museums, in particular, the object is important because it has artistic merit. The style, the execution, or the visual impact are what bring it meaning and significance as a tangible object.

In other instances, especially in history-focused museums, objects carry significance as witnesses — something that was present at a historical event, carried by an important person, or otherwise is meaningful because of where it was or who used it. That connection makes them meaningful for visitors and helps tell the story of the event or the person it bore witness to. John Limbert’s clothing bore witness to the entire 444 days of his ordeal as a hostage in Iran.

When donating his clothes to NMAD, Limbert referred to his gift as “a bunch of old clothes.” However, in the context of the museum’s collection and future exhibitions, these “old clothes” have significant meaning and an important story to tell.

Limbert’s clothing joins a significant collection of objects that NMAD has collected to represent this crisis in U.S. diplomatic history. These include a blindfold used on hostage Robert Blucker during his captivity; buttons, flags, and other items representing Americans’ support and solidarily during the crisis collected by hostage Elizabeth Ann Swift and her family and friends; and awards, proclamations, and other “welcome home” materials from Bruce Laingen, who was in charge of the U.S. embassy when he and his colleagues were taken hostage.

Learn more about how you, too can contribute to the NMAD museum collection and about the development of the museum.