The Dedication and Leadership of Ambassador Kamala Shirin Lakhdhir

How does a diplomat become a great leader? Who and what has inspired them?

The National Museum of American Diplomacy helps answer these questions through an exploration of some of the lives of our nation’s most accomplished diplomatic leaders.

Drawing strength and determination from her upbringing, Ambassador Kamala Shirin Lakhdhir now inspires future generations.

Lakhdhir has led a distinguished career, serving nearly 30 years in the U.S. Foreign Service. She has advanced U.S. policy priorities and fostered cooperation between the U.S. and foreign nations through her prior positions in Riyadh, Jakarta, Beijing, Belfast, Kuala Lumpur, and Washington.

Throughout her diplomatic career, Lakhdhir has looked to her lifelong influences and personal values as guiding forces, approaching challenges with formidable dedication and proactive leadership.

Navigating Two Heritages During Her Childhood

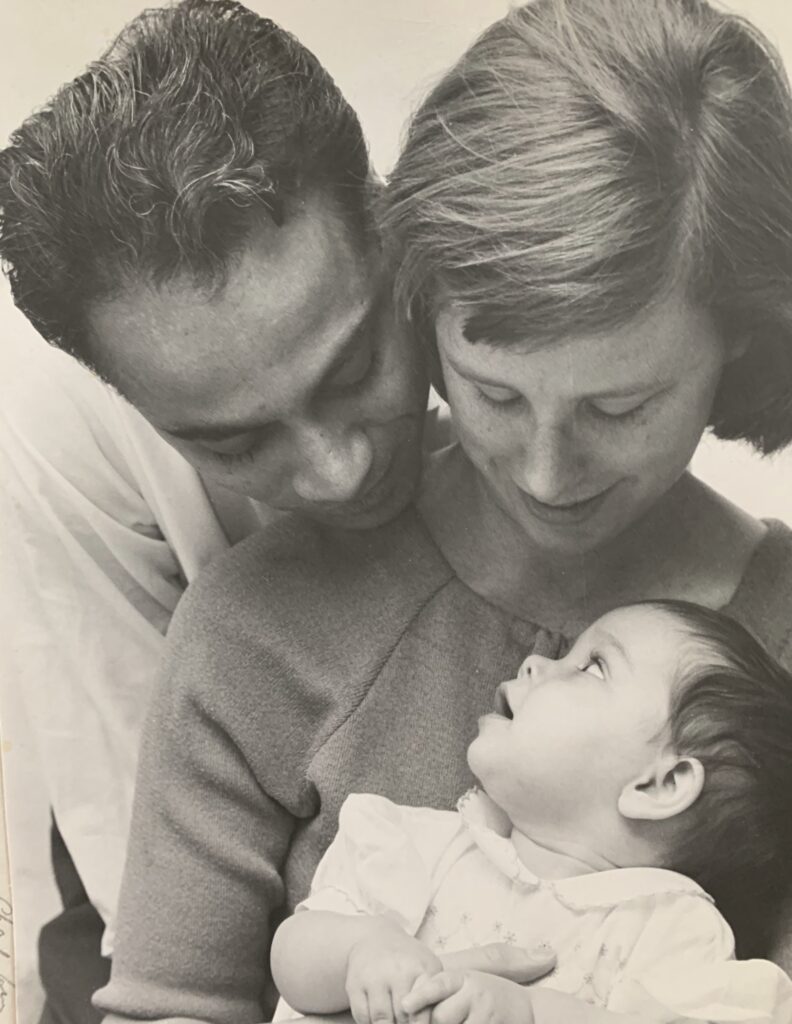

Growing up in Westport, Connecticut, Lakhdhir’s parents inspired her to pursue an international career. Her father, Noor, immigrated to the United States from Mumbai, India, to attend the University of California, Berkeley in the 1940s. While in New York City for his MBA at New York University, Noor met Lakhdhir’s mother, Ann, while living at International House in Manhattan.

Ann was always interested in foreign relations, graduating from Columbia University and serving as President of the Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) Committee on Disarmament, Peace, and Security at the United Nations. According to Lakhdhir, her parents’ shared love of the world was paramount in bringing them both together – they first met over a discussion at the International House on whether the People’s Republic of China should take over nationalist China’s (Taiwan) seat at the United Nations.

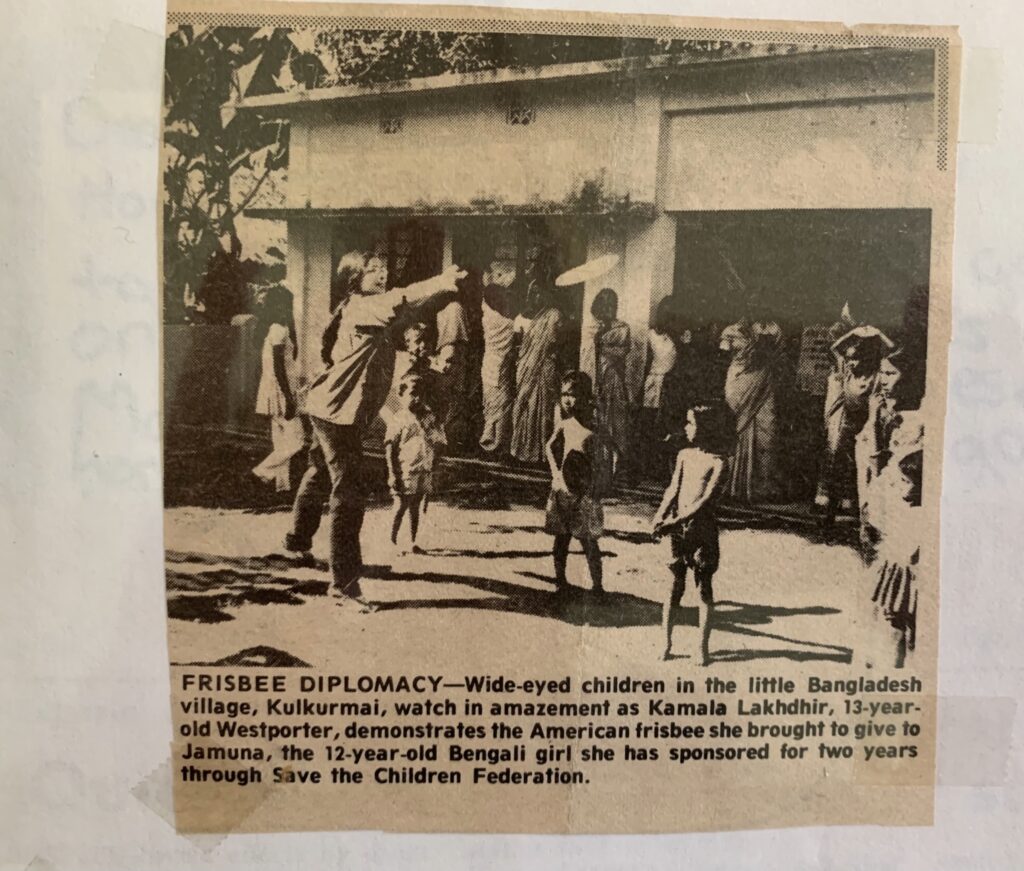

Lakhdhir says her “international career began as a child” as a result of her parents’ rich international background and family trips abroad. These experiences encouraged Lakhdhir to begin her career overseas as a teacher in China for two years after graduating from Harvard College in 1986.

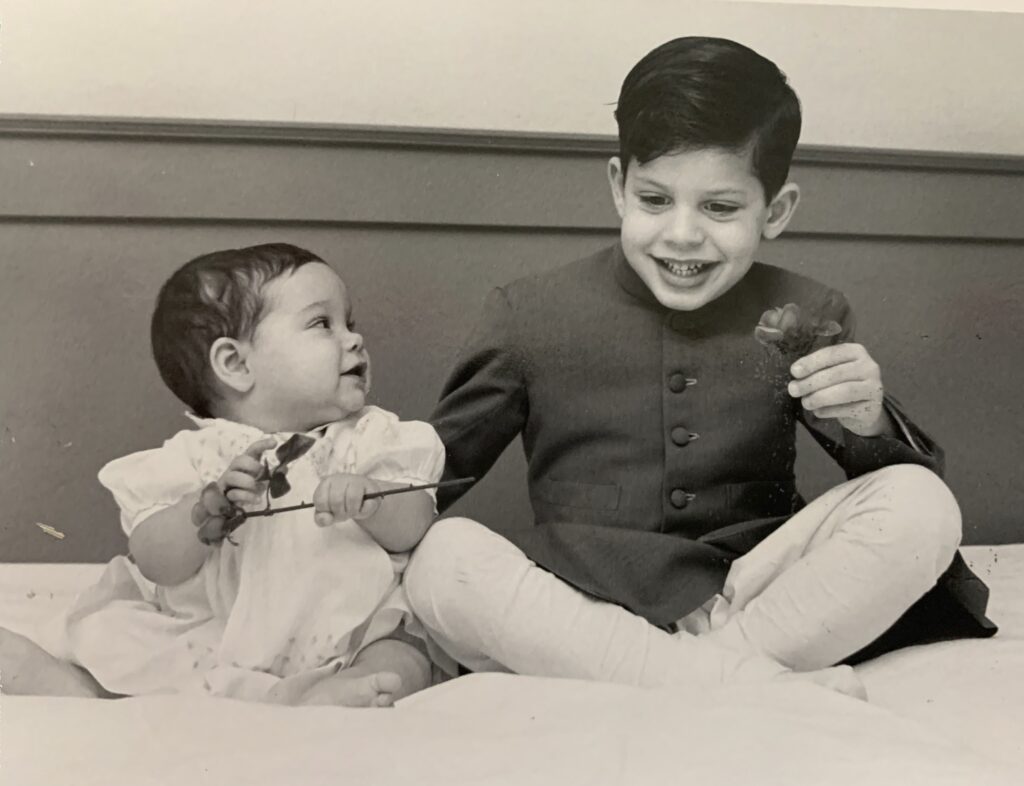

Lakhdhir’s upbringing was also influential in developing her perceptions of herself as a multi-ethnic woman. As a first-generation immigrant from South Asia, her father initially encouraged Lakhdhir and her brother to pursue career paths in science or engineering, given his faltering faith in global political regimes. He was sometimes hesitant to share his Indian culture with his children thinking it might create obstacles for them. As Lakhdhir put it, “My dad made a decision early that his children were going to be American.”

While her father eventually greatly supported his children’s professional choices, Lakhdhir largely credits her connection to her Indian heritage to her mother. Lakhdhir’s mother, Ann, exposed her and her brother to South Asian culture.

Ambassador Lakhdhir’s relation to both her respective identities is so strong that asking her to choose which one she more closely identifies with would be like “asking her to deny her mother or deny her father.” These rich personal experiences have enabled her to foster cultural empathy and build bridges with people across the world.

Her “Mother’s Revenge:” Confronting Challenges as a Woman in Foreign Service

Ann’s personal experience with the Department of State was quite literally the catalyst for Lakhdhir’s career in the Foreign Service.

In 1955, Ann was one of the highest testing applicants for the Foreign Service but was denied a position due to the Department’s ban on married women serving in the Foreign Service.

During her oral assessment, Ann was asked about her plans to marry. She answered truthfully, knowing that either response risked failure. Should she admit she wanted to marry and fail the assessment due to the ban? Or should she deny wanting to marry and fail the exam for being out of step with cultural norms?

She responded that she would eventually like to get married but wanted to have a career first. The examiners assessed that she was not seriously committed to pursuing a career in the Foreign Service. Instead, she was told to marry a Foreign Service Officer, as she would make an excellent ambassador’s wife.

FROM THE COLLECTION

Foreign Service Girl Book

Thirty-seven years later, in 1991, Lakhdhir did what her mother had been denied and joined the Foreign Service, due in a large part to her mother’s keen persuasion. Ann encouraged her daughter to apply for the Foreign Service, but Kamala only agreed under the condition that both she and her mother apply together.

Both passed the written test, but only Kamala passed the oral exam. When Kamala received a call several years later to join, she initially refused the offer as she was then working for the New York City government and pursuing a graduate degree in public finance at New York University. She received a follow-up call reoffering her the position three months later, which she accepted. Lakhdhir jokes, “I always say I was having a bad day at the office and that’s why I joined the Foreign Service.”

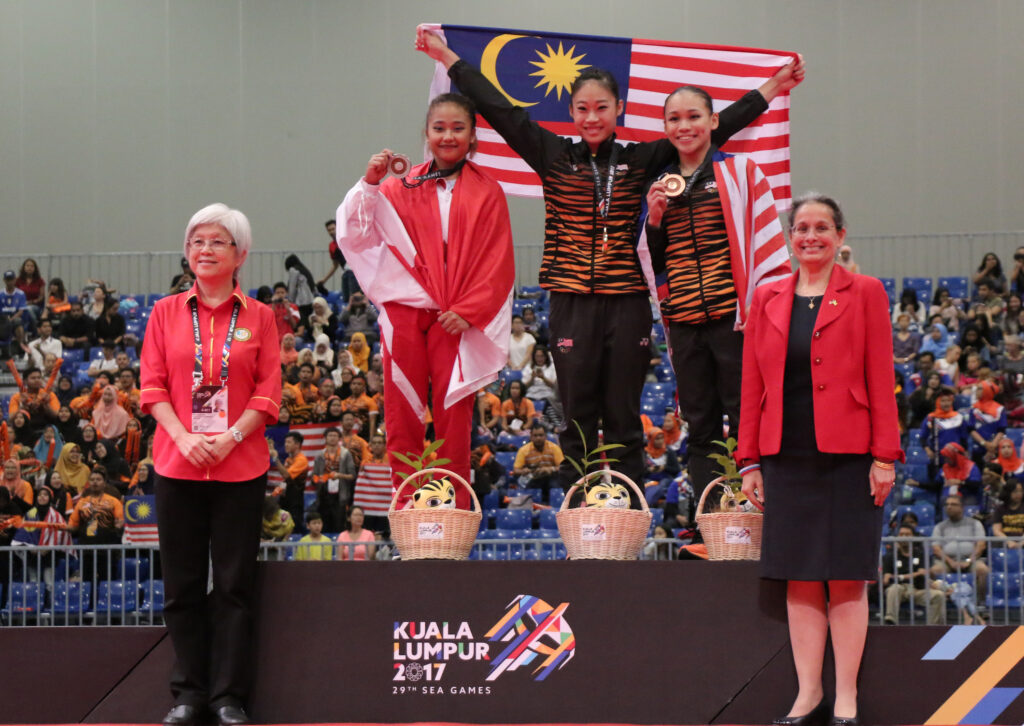

Her mother’s difficulty in gaining entry in the 1950s was not forgotten, nor was her influence throughout Lakhdhir’s life and professional career. An ode to her mother and career in the Foreign Service, Lakhdhir gave a speech during her time at the U.S. Embassy in Malaysia titled: “I am My Mother’s Revenge.” The speech relayed how she was able to accomplish what her mother dreamt of doing but couldn’t due to societal and gender barriers.

Alongside her mother, Lakhdhir recognizes many other women, both within her family and her professional network, as significant role models throughout her career. Hailing from a long line of women activists, Lakhdhir looks to the formidable women within her family as examples of strong leadership. She also expressed her gratitude for the many women supervisors and mentors she has encountered in her time at the Department, including her supervisors during her first Foreign Service tours in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and Jakarta, Indonesia.

Lakhdhir acknowledges it is still a challenge to be a woman Foreign Service Officer due to the dual commitments and responsibilities many women must manage between work and home. Because of that reality, many women do not put themselves forward for leadership roles or demanding positions, and more could be done to make these roles more accessible for women.

Looking Ahead: The Next Generation of International Leaders

In addition to the challenges women face in the U.S. Department of State, Lakhdhir realizes the importance of creating a more diverse and inclusive environment for current and future generations of civil servants, Foreign Service, and locally employed staff around the world. She feels that the first step to achieving greater diversity, equity, and inclusive outcomes is to have more honest conversations. Molding new employees requires work, time, and commitment from the Department, and so does the effort to foster a more representative workforce and culture, according to Lakhdhir. She stated,

“We are, as an organization, on a journey with our own society, one that will continue to grow in diversity.”

– Ambassador Kamala Lakhdhir

She also added that the skills each person brings from diversity in identity and experience open doors: “A good State Department employee brings all his or her tools to the table and uses them – we’ve got our brains, personality, work ethic and we’re constantly utilizing them to engage people and advance our goals.”

Lakhdhir cites mentorship as an important vehicle, both in her own success and as a way for the next generation to determine their own respective career paths. She notes, “I had a network of people that gave me good advice and weren’t afraid to tell me when I was going the wrong way.”

Continuing to advocate for State Department staff, Lakhdhir stresses that listening and being receptive to people’s input of all ranks and career tracks is an important part of building networks. Only in having these candid discussions, she believes, will there be progress internally within the Department and in our diplomats’ ability to fully advance and represent the policies and values of the United States on the international stage.

About the Author: Alisha Rajan is a Program Advisor in the Office of Global Programs and Policy with the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs at the Department of State. She is also a Member at Large with the Department of State’s South Asian American Employees Association.