The Legacy of Edward R. Dudley: Civil Rights Activist and the First African American Ambassador

In 1949, Ambassador Edward R. Dudley was the first African American to hold the rank of ambassador. His legacy also includes a long history of civil rights activism and a distinguished career as an attorney.

Edward R. Dudley’s career before diplomacy

Before becoming an ambassador, Dudley had a distinguished career as an attorney.

Ambassador Dudley was a civil rights lawyer in the 1940s, appointed to the New York Attorney General’s Office. He was then recruited by Thurgood Marshall to become a Special Assistant at the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Subsequently, he became the Legal Counsel to the Governor of the U.S. Virgin Islands, moving there with his young family.

Representing the United States in Liberia

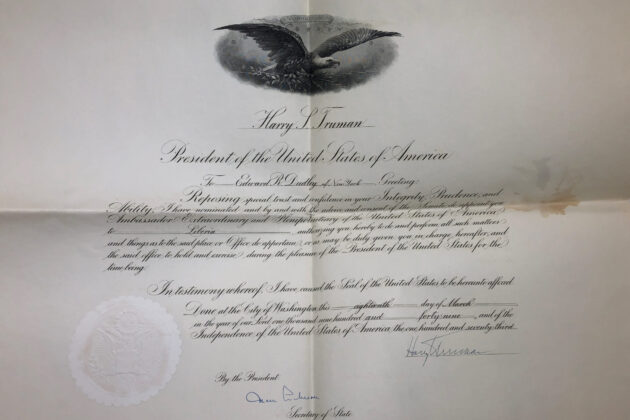

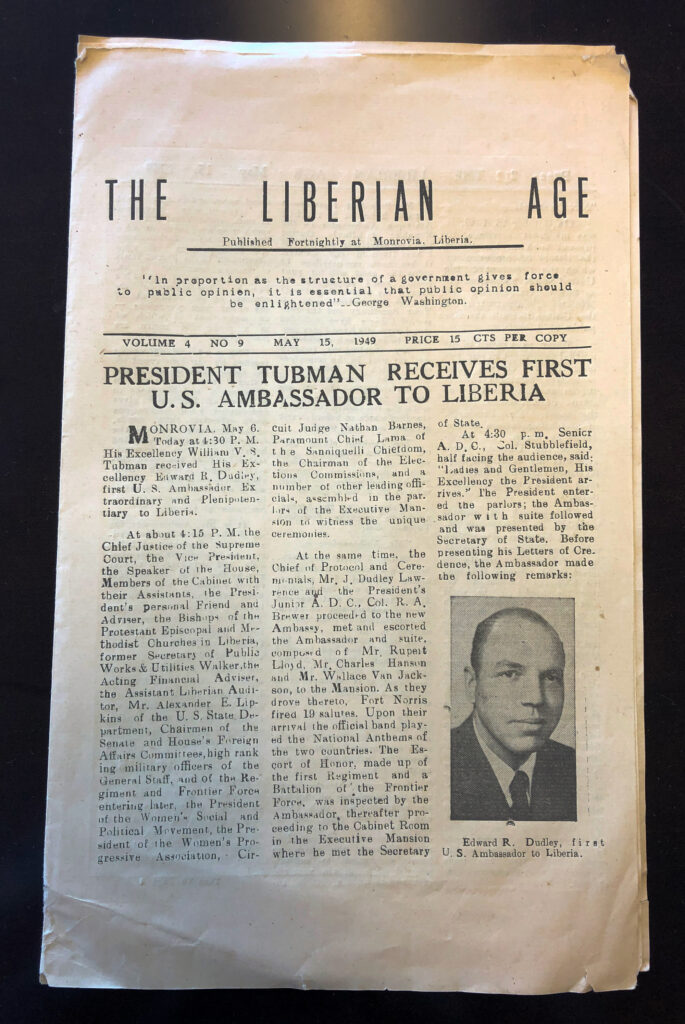

In 1948, President Harry Truman sent Dudley to Liberia as U.S. Envoy and Minister. Upon elevation of the Mission in Liberia to a full U.S. Embassy in 1949, Dudley was promoted to the rank of Ambassador. With that, Ambassador Dudley became the first black Ambassador in U.S. history. This also made him the highest-ranking diplomat, often referred to as the Dean of the Diplomatic Corps, in Liberia’s capital of Monrovia.

After departing Liberia in 1953, he continued to practice law and was later elected to the New York Supreme Court in 1965, serving on the high court until 1985.

FROM THE COLLECTION

Edward Dudley's Commission as Ambassador to Liberia

Serving in the Foreign Service as an African American

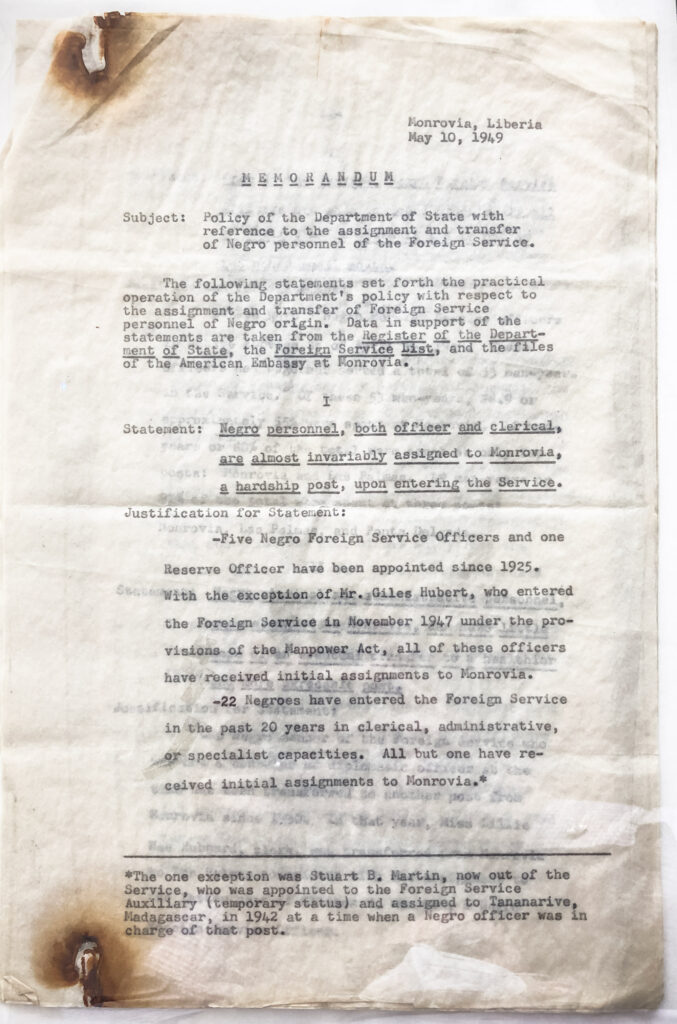

During an oral history interview with the Association of Diplomatic Studies and Training, Ambassador Dudley recounted what he considered his highest achievement in Liberia. During this time, African American Foreign Service officers were stuck in what was pejoratively called the “negro circuit.” Dudley describes their situation: In Liberia “…the leading black foreign service officer there had never had the opportunity of serving anywhere else in the world, despite the fact that it was a policy of our State Department to rotate foreign service officers about every two years….”

“…Despite the fact that we had scores of black people—men and women—in both the Foreign Service Officer corps and in the other areas of government such as secretaries, clerks, other people, none had ever gotten outside of a little triumvirate there that we called Monrovia, Ponta Delgada and Madagascar—all black, hardship, disagreeable posts.”

– Edward R. Dudley

“This had been going on for year after year after year, after year…. I am reminded of one man by the name of Rupert Lloyd, a graduate of Williams College, who had been serving in the Foreign Service when I got there at Monrovia for almost ten years. Another fellow, William George, who had just moved over to one of the other hardship posts…. There had been one woman they told me who had been there for almost twenty-five years. She’d gone when I got there. Another one for seventeen years. So I decided to check into it and I got the staff to prepare some research on it, and I did some myself.”

“We put together a memorandum which was a statement documenting every black in the Foreign Service over a long period of years: where they were; when they came into the service; how long they had been in; and, the fact that they had never been transferred. And next to that we added a class of white Foreign Service officers that we took from the register who came in at the same time as Rupert Lloyd came in and we showed where they had been. In every instance, they had had four, five, six transfers and had been in three, four, and five different posts throughout the world, and very few hardship posts.”

“Well, right away you would know that there was something wrong…and I knew exactly what to do…. I asked for an audience with the Under Secretary of State…. it was his responsibility to correct what was not only an unwholesome situation but, in my judgment, an illegal situation since the Foreign Service Act had indicated that discrimination of this kind was not to be permitted.”

“….[W]ithin six months time, transfers came through and the number one Foreign Service officer was sent to Paris, France: Rupert Lloyd. And this is the first time that a black Foreign Service officer had ever served in Europe. A second Foreign Service officer, Hanson, was sent to Zurich, Switzerland, and a young lady of great talent was sent to Rome, Italy. They even cleared my code clerk—a fellow by the name of Mebane—out and he was sent to London, England, and they moved the people out so fast that the Liberians complained and said, ‘What’s happening?’”

“In my judgment this was probably one of the more important things that I did the whole time I was there, not so much between the relations of Liberia and the United States, but for black Americans. We think we opened the door and stopped this kind of discrimination.”

– Edward R. Dudley

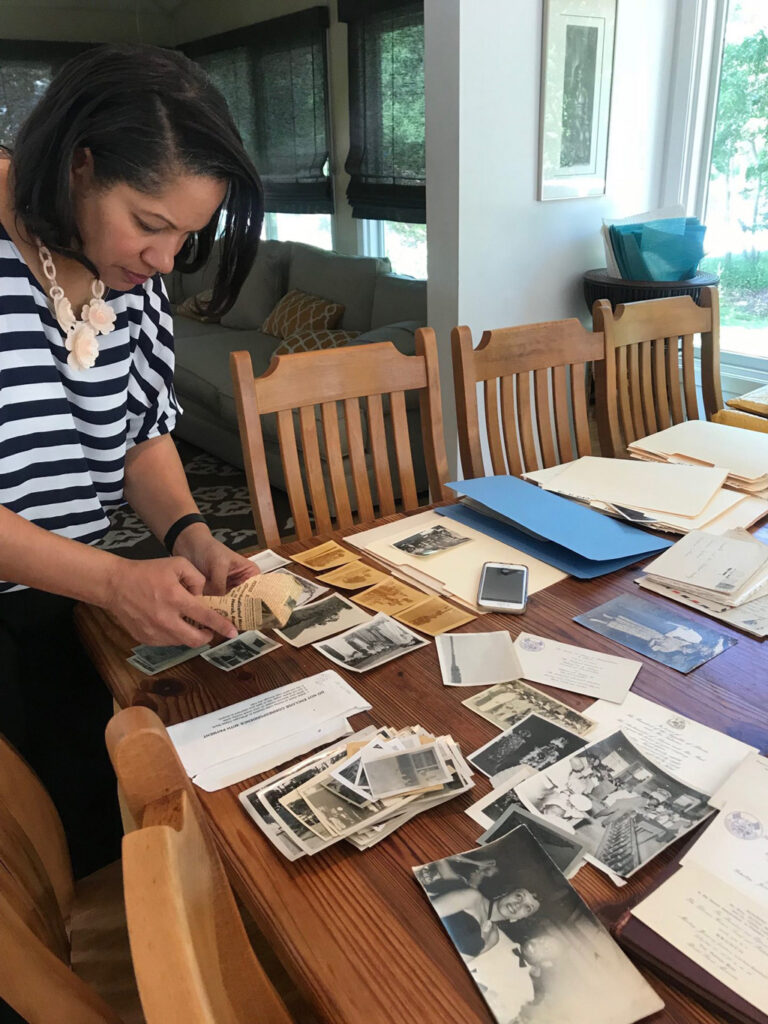

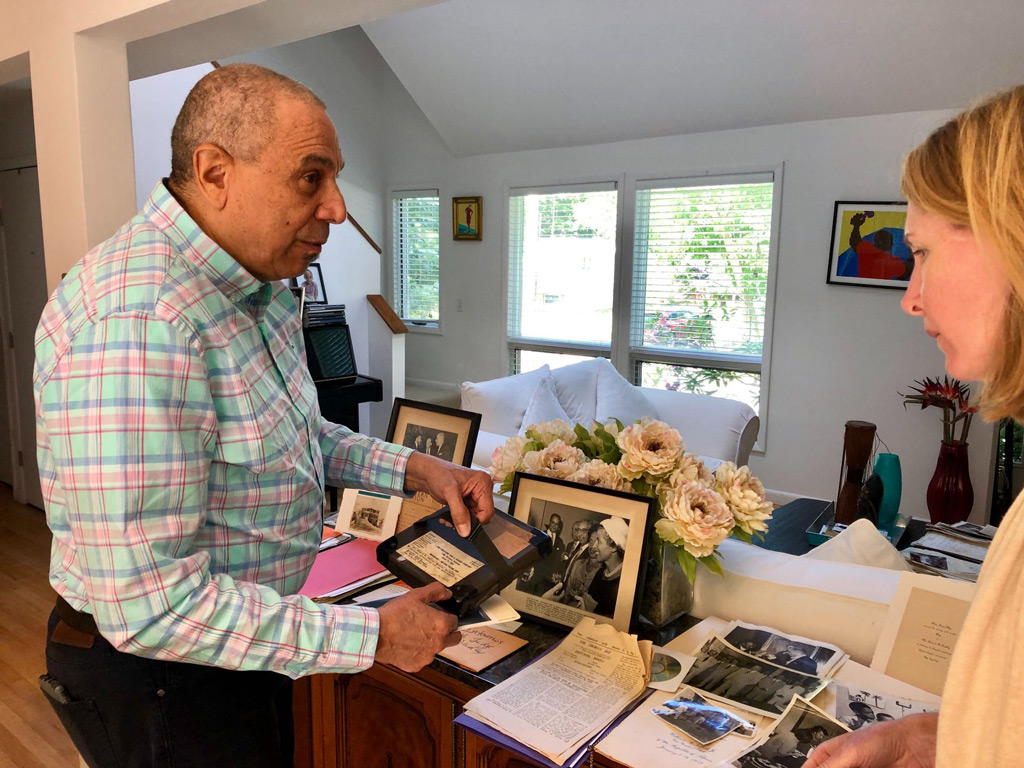

Artifact Donations to the National Museum of American Diplomacy

In 2019, Ambassador Dudley’s son, Edward Jr., donated his father’s extensive archival collection from his time serving as the head of the U.S. mission to Liberia from 1948 to 1953 to the National Museum of American Diplomacy (NMAD). NMAD is truly honored to receive this generous gift. Increasing the diversity of diplomats represented in the NMAD’s holdings is a top curatorial priority. We are proud to preserve Ambassador Dudley’s collection and honor his powerful story.