The Monroe Doctrine: The United States and Latin American Independence

In 1823, President Monroe gave a speech before Congress. Part of this speech became the Monroe Doctrine: a U.S. foreign policy framework about the Western Hemisphere. This framework would affect relations with newly independent Latin American nations for years to come.

What is the Monroe Doctrine?

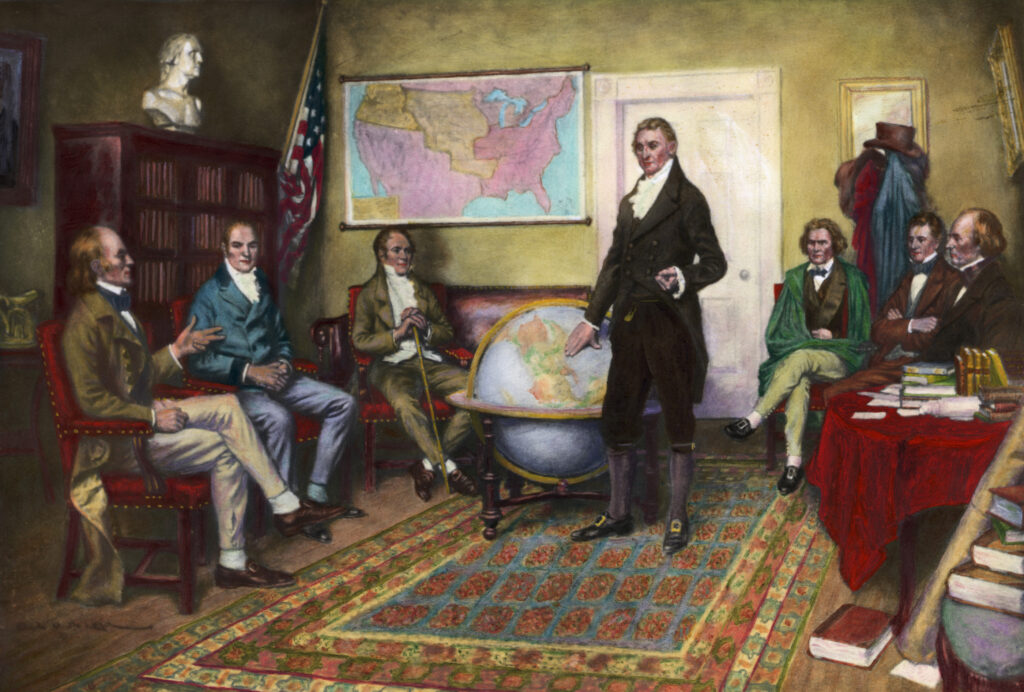

The Monroe Doctrine is a U.S. foreign policy framework addressing America’s security and commercial interests in the Western Hemisphere. It emerged from three paragraphs in President James Monroe’s annual address before the U.S. Congress on December 2, 1823.

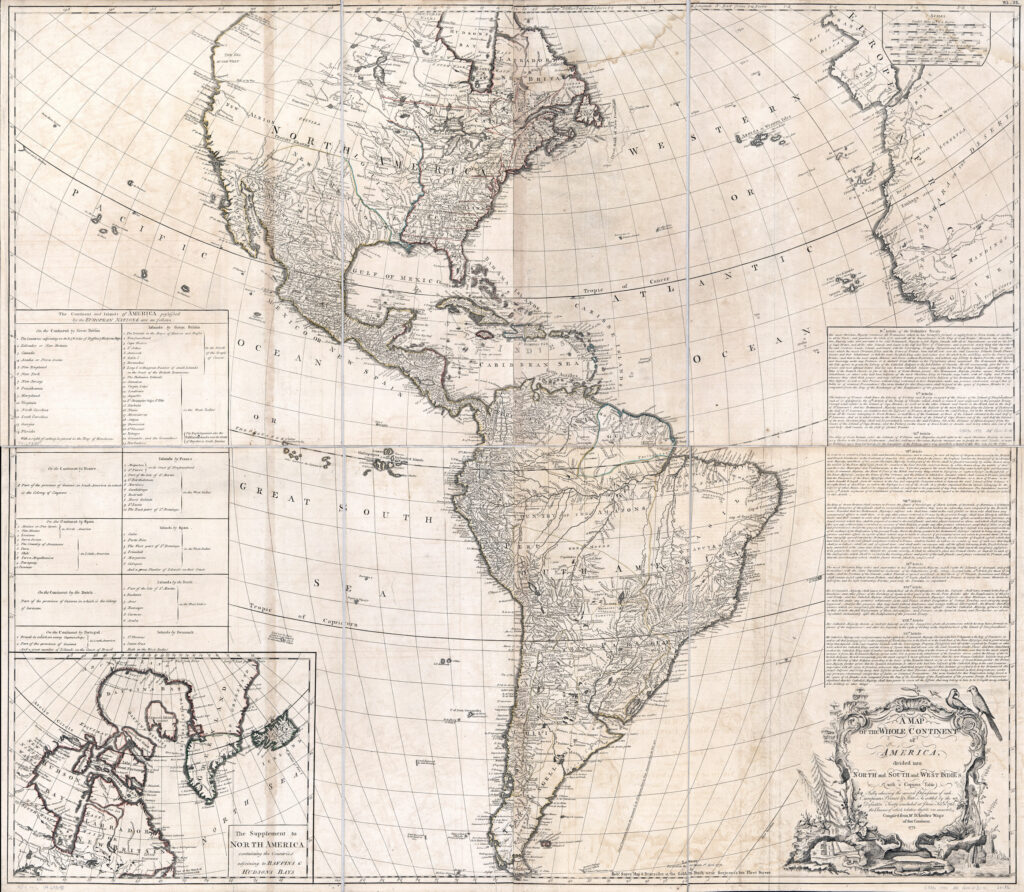

The doctrine addresses how the United States would conduct foreign relations with newly independent nations in Central and South America and how to curb European ambitions in Western Hemisphere territories.

“As a principle in which the rights and interests of the United States are involved, the American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintained, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for colonization by any European powers.”

President Monroe, Seventh Annual Address before Congress, 2 December 1823.

Who wrote the Monroe Doctrine?

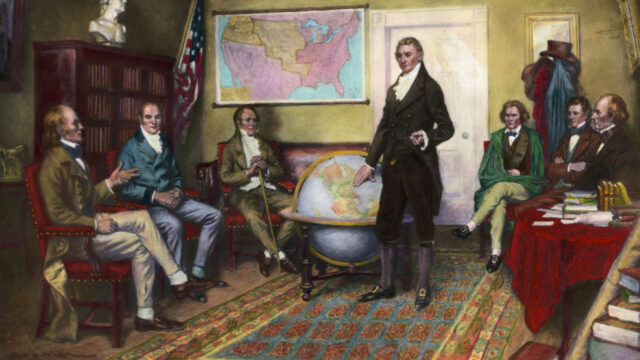

President Monroe gathered his cabinet members together in the fall of 1823. They discussed how the United States should tackle the possible threat of European nations recolonizing Spain’s former colonies, now self-professed independent nations.

Their meetings informed the tone and content of the president’s annual address. Monroe wrote the text of the speech himself with input from his cabinet, along with direct contributions from Secretary of State John Quincy Adams.

Who was the intended audience?

President Monroe gave the speech in person before Congress and handed out written copies to senators and representatives afterward. However, Monroe intended for the message to reach the American people.

“[The people] are sovereign…it is indispensable that full information be laid before them on all important subjects. If kept in the dark, they must be incompetent to it.”

President James Monroe

Citizens learned about an administration’s policies from their state representatives and their local newspapers. Monroe also intended for his message to reach the great European powers of Great Britain, France, Austria, Prussia, and Russia. Diplomats from those nations conducting international affairs in Washington, DC wrote letters to their home governments and often included newspaper articles.

Why did Monroe think this statement was necessary?

The statement had much to do with the independence of the United States itself.

The Spanish monarchy had controlled trade in its Latin American empire through a mercantilist system—restricting and controlling trade to benefit the empire. This system was used throughout the monarchies in Europe and was one of the reasons the American colonies rebelled against Great Britain in 1776.

The American colonies wanted to engage independently in free trade. The same was true of the newly independent Latin American nations, which could now openly trade with the United States.

Great Britain shared this concern. Its Foreign Minister, George Canning, offered to issue a joint statement with the Americans against recolonization in the Americas. Monroe received advice from many senior statesmen, including Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who urged him to accept the proposal.

In the end, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams persuaded Monroe to issue an independent statement. He argued that issuing an independent foreign policy statement equated to the independence of the United States itself, free to conduct its foreign affairs without influence from other nations.

How would recolonization threaten the security and prosperity of the United States?

Between 1810 and 1822, fifteen Latin American colonies declared independence from the Spanish empire; ten alone between 1821 and 1822.

Unsure of their ability to maintain independent democratic governments, Monroe’s administration hesitated to recognize these new nations. Anti-Catholic sentiment also ran high in the United States. Some government officials argued that democracy could not survive under the Pope’s perceived influence over the people.

But hesitation in recognizing new nations did not stop Monroe from issuing his statement against the threat of recolonization. If European powers conquered these republics, the United States’ new commercial ties would be lost.

Also, the center of power would again revert back to Europe. The Americans would again be in the position of having to negotiate with the European power, rather than the people.

Since empires are built on exploitation and suppressing individual liberties, the U.S. government shuddered at the thought of that influence once again at America’s doorstep. Empires are expensive to maintain and require a strong military to guard their interests, which also could present a threat to national security.

Did the United States send diplomats to the newly independent Latin American nations?

Yes, but not immediately.

The United States had dispatched Joel Roberts Poinsett to Chile in 1811 to gather intelligence about regional independence movements. It was not until early 1824 that Monroe sent diplomats to other new nations after making the foreign policy remarks in his December 1823 address. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams gave these diplomats specific instructions on how they should follow Monroe’s policies.

“With relation to Europe, there is perceived to be only one object, in which the interests and wishes of the United States can be the same as those of the South American nations, and that is that they should all be governed by republican institutions, politically and commercially independent of Europe.”

Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, on his instructions to Latin American diplomats

But Adams also cautioned the diplomats to be wary of these new governments. There was no guarantee they would use the U.S. government as their example, nor should they forget the differences between the British and Spanish empires.

When did people begin referring to the principles Monroe outlined as the Monroe Doctrine?

President James K. Polk wrote about U.S. territorial ambitions in the context of “Mr. Monroe’s Doctrine” in his diary in 1845. A year later, the United States declared war with Mexico, which ended with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848.

The Treaty increased the United States’ territory by 525,000 square miles and included what would become California and Texas. Some U.S. politicians used the Monroe Doctrine’s principles to justify an aggressive war against its neighbor.

But it wasn’t until the late 19th century that politicians began openly using the Doctrine as a means to argue for intervention in Latin America. They also used it as a means to increase U.S. influence in the western hemisphere.

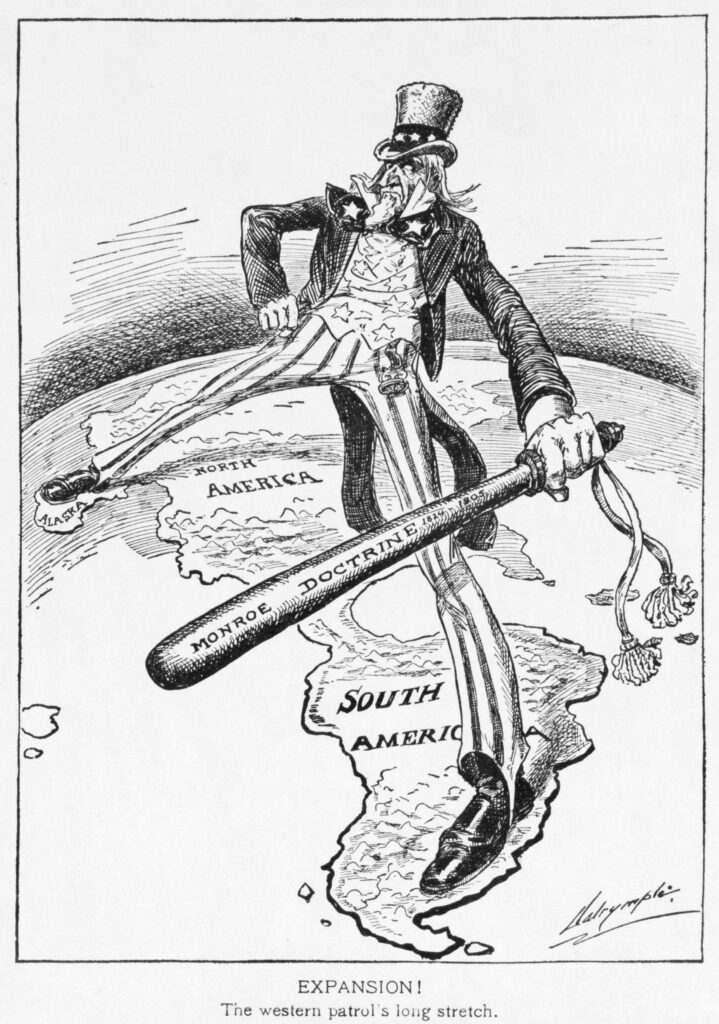

Lacking military means, there wasn’t much the United States could do to enforce the Doctrine until after the American Civil War when the U.S. built up its navy and expanded its diplomatic presence. Cartoonists often lampooned the Monroe Doctrine to argue for and against American dominance in Latin America.

Sources Consulted and for Further Reading

U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian; Monroe Doctrine, 1823

Nicholas Guyatt, “The Adams Doctrine and an “Empire of States,” Diplomatic History, Vol. 47, Issue 5, November 2023, pp. 823-844.

Jay Sexton, The Monroe Doctrine: Empire and Nation in Nineteenth Century America (New York: Hill and Wang, 2012).