The Kellogg-Briand Pact: The Aspiration for Global Peace and Security

August 27, 2021 marks 93 years since the signing of the Kellogg-Briand Pact. The United States and France drafted the treaty, officially known as the General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy, in the decade following the end of World War I.

This historic treaty pursued the lofty goal of ending war. While the treaty was ultimately unsuccessful in eliminating war, it set a global precedent for peace.

World War I Causes Global Devastation

World War I, also known as the Great War, began in 1914 and came to an end in 1918. In that time, Europe saw changes to national borders, advancements in military technology, and public life after the decimation of towns and cities. However, these transformations came with the ultimate sacrifice — millions of citizens and military personnel died during the conflict.

In 1919, the victorious Allies organized the Paris Peace Conference, which was called to establish the terms of peace. The Paris Peace Conference culminated in five major treaties in addition to the creation of the League of Nations. One treaty, The Treaty of Versailles, took aim at Germany as the key belligerent during the war. Against the United States’ warnings of caution, France and Great Britain spearheaded the terms of the treaty, aiming to punish Germany for its role in the war. The Treaty of Versailles demanded Germany disarm its army and navy, concede pre-war territory, and pay extensive reparations.

The Treaty of Versailles was not unique in its demands. All treaties resulting from the Paris Peace Conference altered the political and geographical landscape of Africa, Europe, and Southeast Asia. People living in these areas were denied the opportunity for self-determination and were declared colonies of Great Britain, France, or of another Allied nation. When these treaties were ratified, questions were prompted about the future of global politics. Could peace prevail within the new parameters?

France Proposes a Peace Pact to the United States

New peace treaties and different land and military concessions after the war created an uncertain world. In Russia, Bolshevism and communism had taken root. The new spread of communist ideologies frightened many Western nations, who saw it as a threat to democratic ideals. Global and national economies were depleted by the costly war. The League of Nations offered little stability, as it had no internal leadership, therefore no international authority.

In light of the chaos and sheer loss of life during the war, French Minister of Foreign Affairs Aristide Briand publicly proposed a peace pact to the United States. In a letter to the Associated Press, Briand thanked the United States for its assistance during the war and requested the U.S. government to join France in “outlawing war.”

Briand understood that the United States government could not ignore a public call for peace. The American public was angry that it was pulled into the European war, for which they believed they had no valid stake. Moreover, American businesses suffered during the conflict due to disruptions in trans-Atlantic supply chains. Another war would certainly cause another popular despair and economic dilemma.

While Americans would be keen to support such a proposal, it also served France. About 1,700,000 French died during the war, depleting their military, economy, and public morale. If another hostile power such as Germany were to rise again, France would quickly be defeated.

A peace agreement between the longtime allies seemed obvious, but U.S. President Calvin Coolidge and U.S. Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg were hesitant.

Coolidge and Kellogg saw the proposal as a binding and unfavorable agreement for the United States. Such a treaty would imply that the United States would be required to intervene if France had any sort of military threat again.

Secretary Kellogg and a Treaty to Outlaw War

Unwilling to put the United States in a position where it may have to go to war to defend an ally, Kellogg responded with an equally appealing counteroffer. He suggested an open invitation to all countries to join the United States and France in a pact to outlaw war. Coolidge and Kellogg knew it was impossible that all nations would agree and comply. However, by opening the discussion to more voices, focus shifted away from the United States specifically and broadened it to include all potential stakeholder nations.

The agreement became known as the Kellogg-Briand Pact in recognition of its primary creators and was signed in Paris, France, on August 27, 1928. The main text has two articles:

- Signatories shall renounce war as a national policy and;

- Signatories shall settle disputes by peaceful means.

The broad terms allowed room for interpretation by signatories to still act in self-defense, abide by other post-war treaties, and pursue general military action. An initial 15 nations signed the treaty. The number of signatories eventually grew to 47.

FROM THE COLLECTION

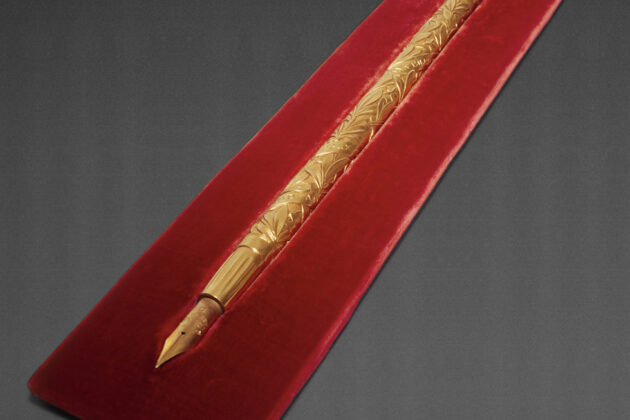

Kellogg-Briand Pact Signing Pen

Putting the Kellogg-Briand Pact to the Test

The treaty was put to the test and failed in 1931 when Japan invaded Manchuria, China. It became clear that the Kellogg-Briand Pact proved ineffective in preventing war without enforcement and with undefined legal terms. World War II began just 11 years after its signing.

The pact was not completely unsuccessful, however. It promoted and popularized the idea that aggressive and preemptive military intervention and territory accession were unfavorable, soon becoming the global standard. The ideas outlined in the League of Nations and the Kellogg-Briand Pact were cemented in the creation of the United Nations in 1945. Established to maintain international peace and security and promote goodwill between nations, the UN was on stable ground as an intergovernmental organization with an initial 51 member states, including the United States.

The first example of decreased international acceptance of war for territory accession was seen at the Tokyo Tribunal and Nuremberg Trials, where Japan and Germany were found guilty of waging aggressive wars and obstructing peace. A more modern example is Iraq’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait. Saddam Hussein, then Iraq’s president, invaded his smaller, oil-rich neighbor. The action drew condemnation from the UN, NATO, and all major world powers, as it was deemed a breach of international peace and security.

The Kellogg-Briand Pact has become viewed as a trial-and-error process in diplomacy. Diplomats did not succeed in ending war, but the Pact is an example of the continuous work of improving international security for all.

To explore more about the Kellogg-Briand Pact, Paris Peace Conference, and the world after World War I, consult the Office of the Historian, which prepares and publishes the official documentary history of U.S. foreign policy.

Additional sources consulted: