The Trent Affair: Diplomacy, Britain, and the American Civil War

In 1861, as the Civil War was beginning at home, U.S. diplomats faced a unique dilemma. The United States needed to maintain relationships abroad. At the same time, the self-proclaimed Confederate States of America sought foreign recognition as an independent nation. Domestic politics and international relations became intertwined when Confederate diplomats were taken prisoner from a British ship, starting the Trent Affair.

The resulting negotiations affected both the result of the Civil War and the special nature of the Anglo-American relationship.

The Trent Affair Arises

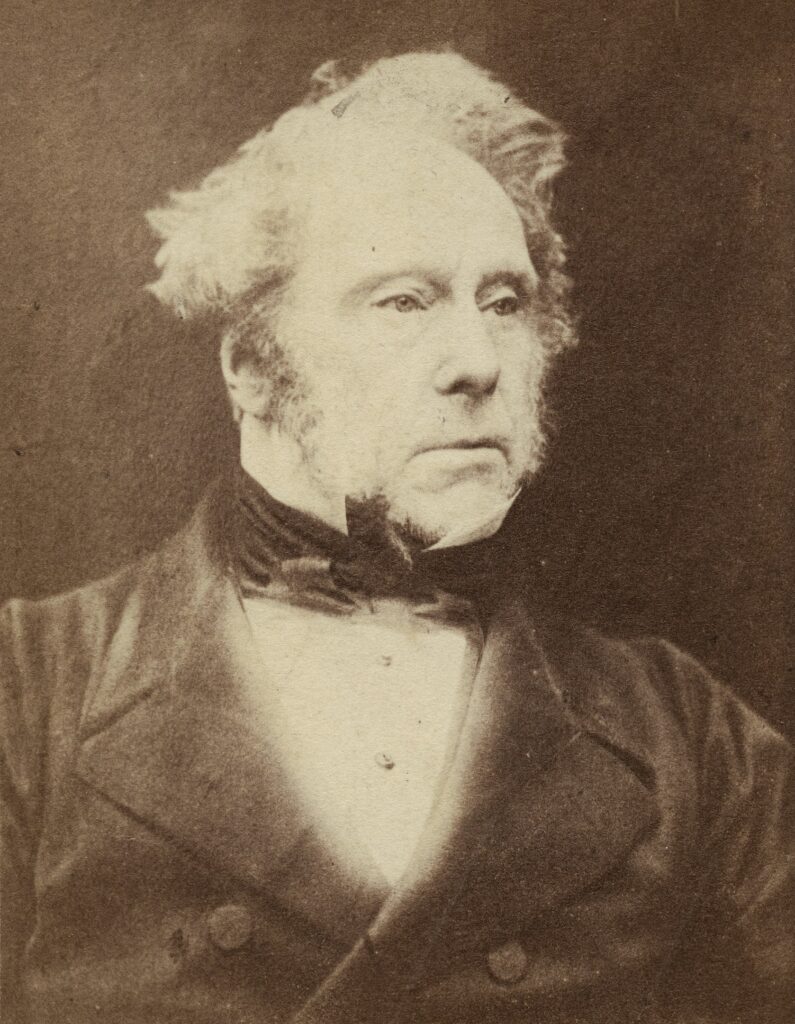

How did the Trent Affair begin? In 1861, Charles Francis Adams served as the U.S. Minister (today’s version of an Ambassador) to the United Kingdom. On November 12th, Adams received a surprising request for a private meeting from the British Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston.

94 Piccadilly, 12 Nov., 1861

My Dear Sir,

I should be very glad to have a few minutes conversation with you; could you without inconvenience call upon me here today at any time between one and two.

Yrs faithfully

Palmerston

Adams usually met with his British counterpart, Foreign Secretary Earl Russell. A summons from the Prime Minister himself was out of the ordinary–and worrisome.

When Adams arrived at the meeting, the Prime Minister got straight to business.

Prime Minister Palmsteron told Adams that an American captain had gotten “gloriously drunk on brandy” in Southampton, England. He was bragging about his plans to capture some diplomats coming to represent the Confederate States of America.

The British government knew what the Confederates wanted–formal recognition of the Confederate states as free and independent from the United States.

Adams later noted in his diary that Palmerston had been “cordial” and did not say whether this interception was legal. But, he did warn Adams to let the U.S. government know that any interception would probably not “lead to any good.”

Unbeknownst to Palmerston and Adams, a different U.S. captain had already seized the two Confederate diplomats four days earlier.

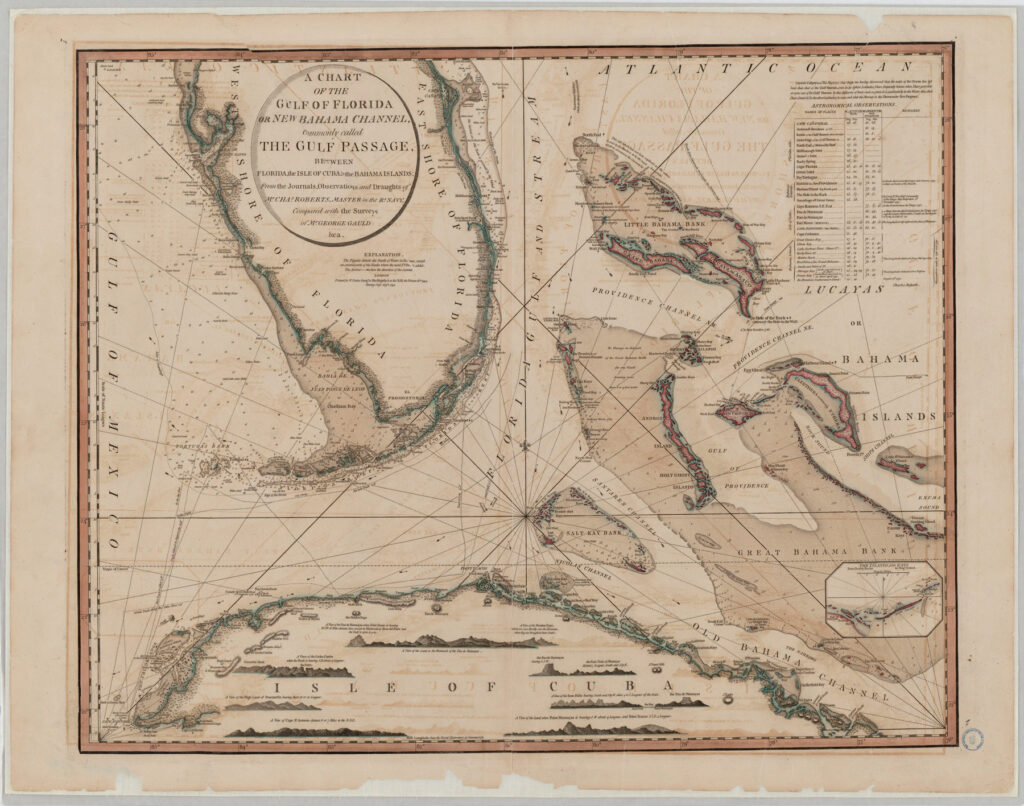

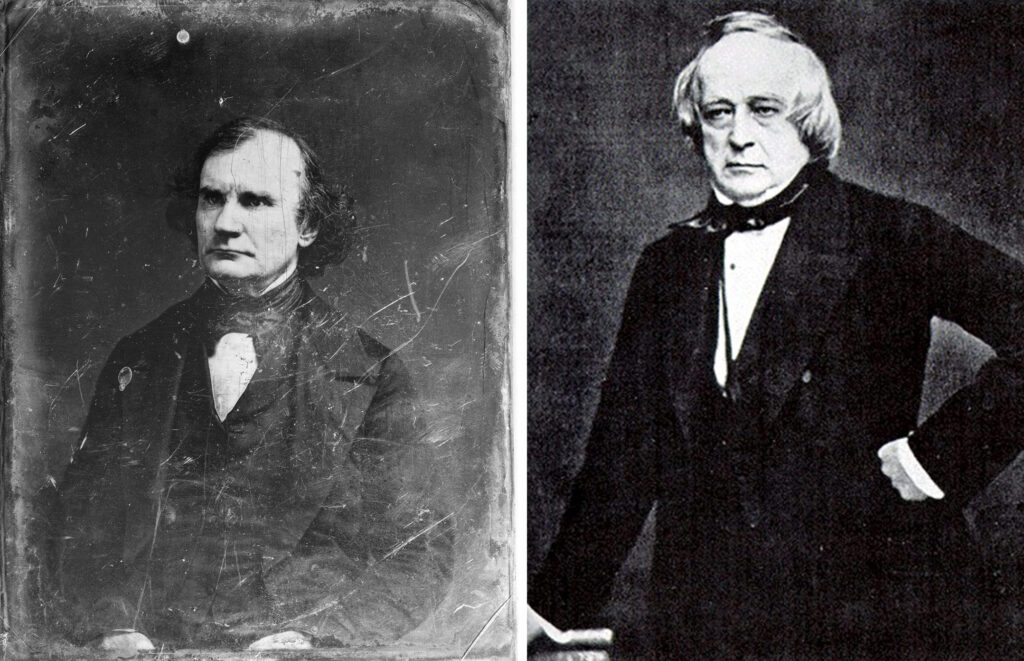

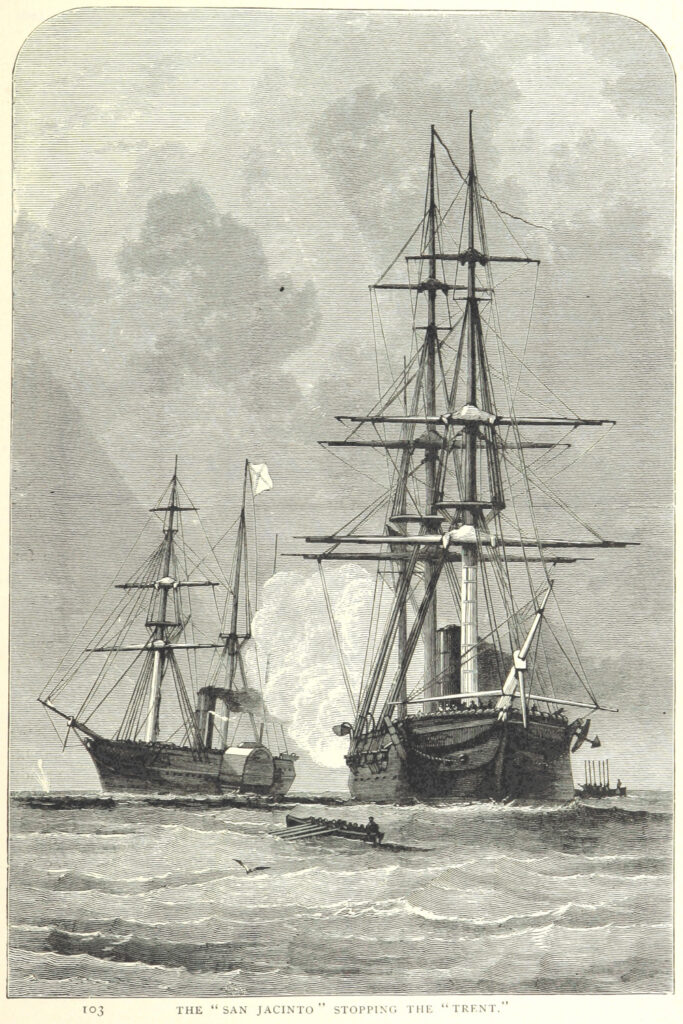

On November 8th, Captain Charles Wilkes of the USS San Jacinto captured James Murray Mason and John Slidell, taking them from the British mail steamer Trent, off the coast of Cuba.

And indeed, as Palmerston had predicted, what became known as the Trent Affair did not lead to any good.

Britain Declares Neutrality in the U.S. Civil War

Charles Francis Adams arrived at his post in London in May 1861 in an uncomfortable situation. He came one day after Queen Victoria issued Britain’s Declaration of Neutrality. This declaration, written in response to President Lincoln’s order to block Southern ports with the U.S. Navy, declared Britain would remain neutral in the U.S. Civil War.

Declaring both the North and South “belligerents” allowed the British to trade with both sides, selling military equipment and importing corn and cotton. However, the Declaration did not go as far as recognizing the independence of the Confederacy. Northerners, including Secretary of State William H. Seward, saw the declaration as a betrayal of Britain’s alliance with the United States and its international opposition to slavery. Confederates, however, rejoiced in the news. The declaration was an opening to lobby European powers for full recognition. Recognition would allow the Confederates to borrow from international lenders to fund the war. Because of this, sending diplomatic envoys to Britain and France became a top priority for southern ambitions.

Diplomacy Before the Telegram

In 1861, the laying of the transatlantic telegraph cable was still five years away. Diplomats on both sides of the Atlantic relied on ships to relay communications. Letters could take four weeks or more to arrive, often requiring diplomats to use their best judgment during conflicts.

As a result, Charles Francis Adams didn’t learn about Mason and Slidell’s seizure until late November when the Trent arrived in England.

Even though the Trent was clearly a British ship, the USS San Jacinto had fired two shots across the bow. Under the command of U.S. Captain Charles Wilkes, the Americans boarded the Trent and captured Mason and Slidell before allowing the vessel to continue its journey.

Captain Wilkes then took Mason and Slidell to Fort Warren in Boston Harbor, where he was given a hero’s welcome. Wilkes was the guest of honor at many celebratory dinners, where he regaled guests with stories of the capture. The British envoy to Washington, D.C., Lord Richard Lyons, reported these celebrations back to Britain. He also repeated a rumor that Wilkes acted under orders from Secretary Seward to seize the diplomats without President Lincoln’s knowledge.

Tensions Rise in Britain; War Rumors Spread

The British were furious at the United States for blatantly disrespecting their sovereignty. Prime Minister Palmerston and Foreign Secretary Earl Russell erupted in a fury at a cabinet meeting. Palmerston shouted, “I don’t know whether you are going to stand this, but I’ll be damned if I do!”

All Charles Francis Adams could do was send letters to Secretary Seward, letting him know of the hot temperature in London. Unable to speak on behalf of the U.S. government without instructions from Seward, Adams could only wait, watch, and avoid meetings with Lord Russell.

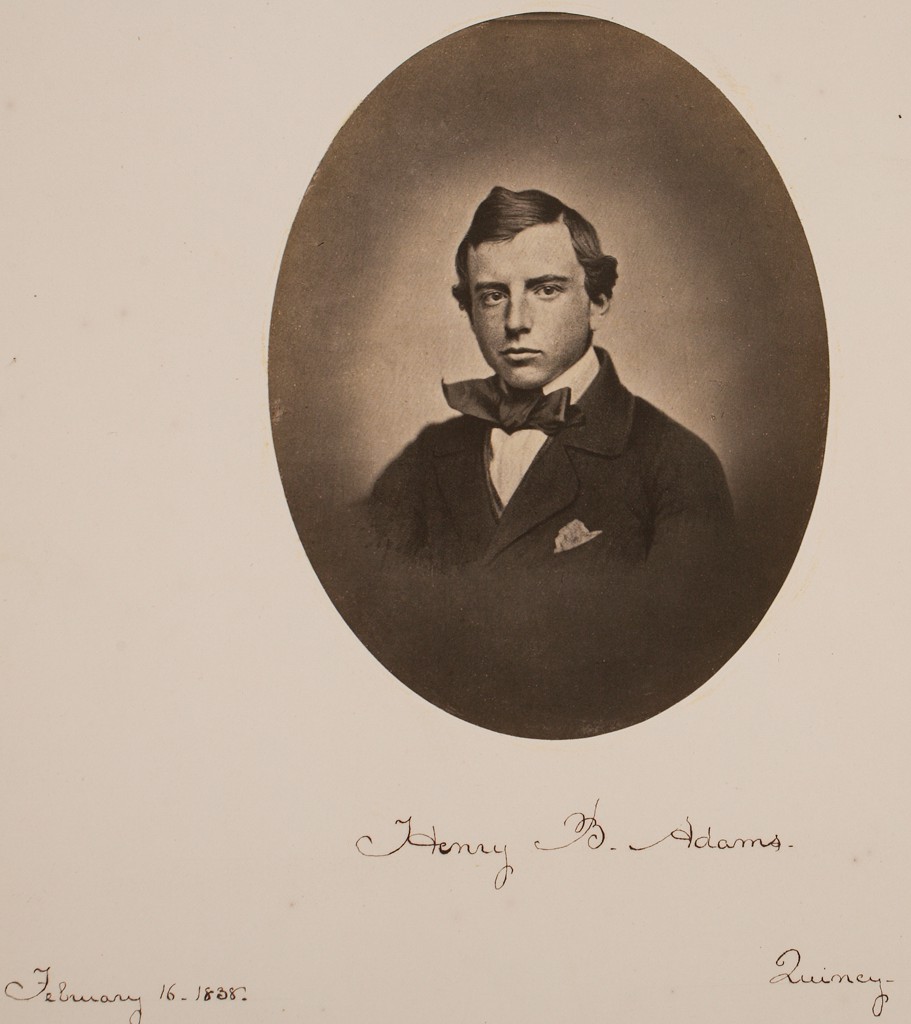

Adams’s son, Henry (who served as his father’s secretary), described the situation:

“I wonder what Seward supposes a Minister can do or is put here for, if he isn’t to know what to do or what to say. It makes papa’s position here very embarrassing, and if he were to see Lord Russell coming along the street, I believe he’d run as fast as he could down the nearest alley.”

– Henry Adamas

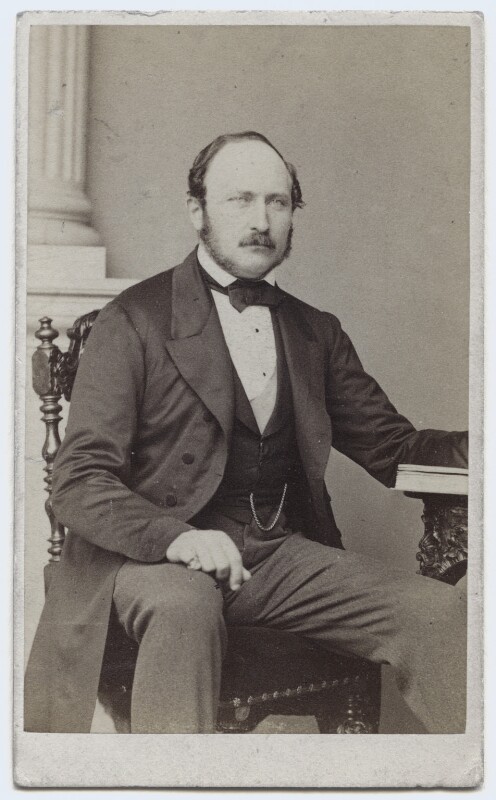

In Britain, there was even talk of going to war with the United States. The news was so alarming that Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband, who was deathly ill from typhoid, rose from his bed to help write diplomatic instructions to Lord Lyons.

Once the instructions arrived in mid-December, Lyons told Seward that the United States owed Great Britain a formal apology. They were to release Mason and Slidell at once into British custody. Lyons’ demands aligned with the tensions Adams had described in his letters, noting that the British had already sent thousands of troops to Halifax, Canada.

The threat of military action worried President Lincoln and Secretary Seward, but perhaps more worrisome was its economic impact. U.S. bond values were dropping, and British investment firms were halting their American operations. In response, Americans began to cash out their U.S. bonds, jeopardizing the government’s ability to fund the war effort.

The U.S. leaders needed to defuse this diplomatic crisis quickly. They needed to appease the British without admitting their capture of the Confederates on foreign ships was illegal.

Lyons had given Seward seven days to respond to their demands. As the days ticked by in December, Seward stalled Lyons as long as possible.

An Emergency Christmas Cabinet Meeting

On December 25, Christmas Day, President Lincoln called an emergency Cabinet meeting. Secretary Seward presented his 26-page response to the British for the cabinet’s approval. In his response, Seward was careful not to apologize. Instead, he carefully laid out the United States’ position:

- Wilkes did not act under official orders from the U.S. government.

- Wilkes had the legal right to stop the Trent and search it.

- What Wilkes did wrong was fail to escort Mason and Slidell and the Trent to a neutral port for arbitration.

As for the Confederate agents, Seward cleverly downplayed their importance almost with a casual shrug. He called them “pretend” diplomats dispatched by a “pretend” President Jefferson Davis. The United States, he concluded, would “cheerfully” turn them over.

Lyons accepted the diplomatic overture on behalf of the British government. On January 3, 1862, Mason and Slidell departed for England.

Diplomacy, pragmatic leadership, and lengthy communication periods helped avert the crisis. A week later, Adams learned about the outcome, but he was only slightly relieved. As the Minister, he would continue to advocate for the United States and discourage the British from recognizing the Confederacy.

Still, Adams was disappointed that Britain had remained neutral and felt personally betrayed. Adams wrote mournfully to a friend, “She has deliberately preferred to sit as a cold spectator, ready to make the best of our calamity, the moment there is a sufficient excuse to interfere.”

For Further Reading

Joseph Fry, Lincoln, Seward, and U.S. Foreign Relations in the Civil War Era (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2019).

Howard Jones, Blue and Grey Diplomacy: A History of Union and Confederate Foreign Relations (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

Charles Francis Adams, “The Trent Affair,” The American Historical Review, Apr., 1912, Vol. 17, No. 3 (Apr., 1912), pp. 540-562.

Ferris, Norman B. The Trent Affair: A Diplomatic Crisis, (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1977).

U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian

Charles Francis Adams to Richard Henry Dana; From the MHS Dana Family Papers Online