Avraham Rabby: How a Disability Rights Advocate Opened the Door for Blind Diplomats

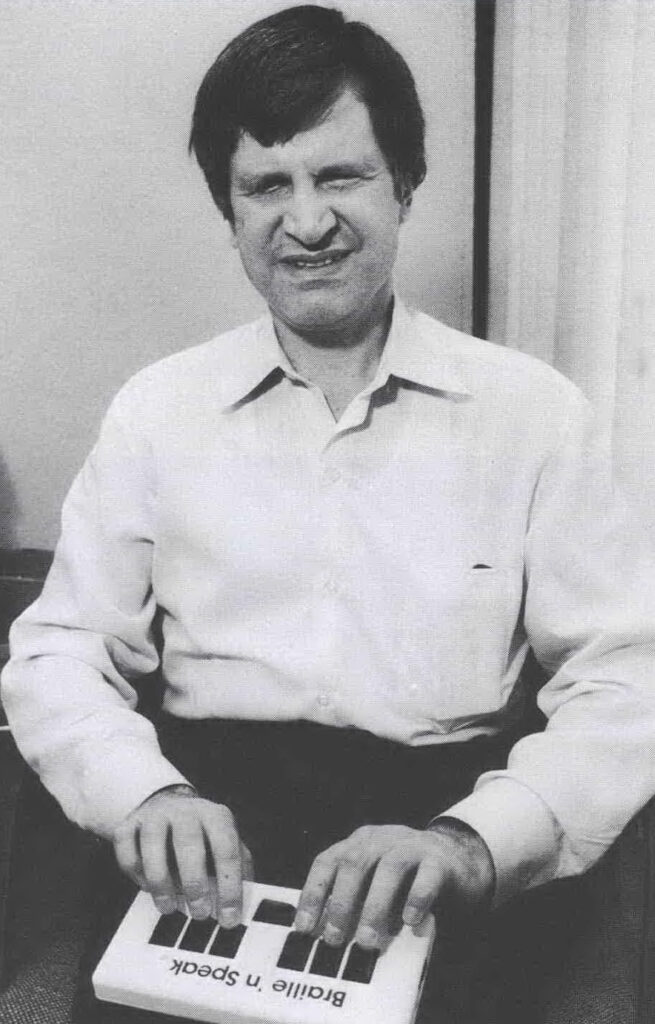

Avraham Rabby was a lifelong advocate for the rights of those with disabilities, particularly vision loss. Rabby was completely blind, having lost his sight as a child due to detached retinas. He also served as a diplomat in the U.S. Foreign Service for 17 years. It was a job he had to fight for.

Rabby, known by the nickname Rami, passed the U.S. Foreign Service exams twice in the mid-1980s. However, he was medically disqualified from becoming a Foreign Service Officer due to his blindness.

Refusing to be deterred and disagreeing with the reasons given for his rejection, he fought back. Early in life, Rabby had learned to advocate for himself when faced with discrimination. He used this skill to persuasively argue that he—and other blind people—could serve effectively as diplomats.

After several years, including giving public testimony in front of Congress and taking his case to the media and courts, Rami Rabby and others finally succeeded in forcing change. In 1990, he and a fellow blind applicant were permitted to join the U.S. Foreign Service and served abroad successfully.

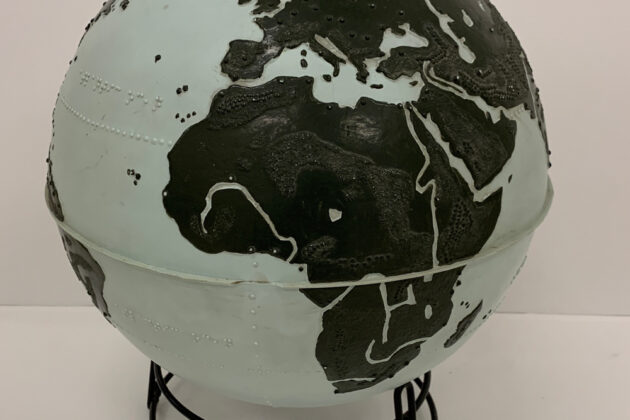

In 2022, Rabby’s family donated items to the museum representing his career in the Foreign Service and his work as a disability rights advocate. From a braille globe dating to his time as a student to an award from the National Federation of the Blind, they help tell the story of his life and work.

“A blind person sees the world differently from a sighted person. Our impressions are no less valid.”

– Avraham Rabby, in a 2007 interview with the New York Times

Rabby Blocked from Becoming a Diplomat

Rami Rabby had the life experience and skills that many would consider ideal for a diplomat. He spoke four languages, lived for significant periods of time in several countries, had a graduate degree, and was a human resources consultant with international clients.

Interested in making a career change in his early 40s, he decided to try joining the U.S. Department of State as a Foreign Service Officer. He contacted the Foreign Service Board of Examiners and was told that blind applicants were allowed and that the Foreign Service exams allowed a range of accommodations—such as braille, cassette tape, and readers—that blind people routinely use.

In July 1986, Rabby passed the second half of the exam. A few months later, he appeared for his mandatory medical examination. A doctor read a paragraph from the State Department’s medical standards manual. It bluntly stated that any person suffering from a noticeable lack of “visual acuity” was to be medically disqualified from joining the Foreign Service.

Rabby kept trying. During his third attempt, he was called a few days before taking the second half of the exam. He was told there had been a change in policy: he could not take the exam with the assistance of a person as a reader of the written materials, as he had previously done both times he had taken the exam.

In a 1988 interview with the Associated Press, Rabby did not mince words about the State Department’s apparent lack of interest in allowing blind people to become diplomats: “It is absolutely unconscionable that the rest of the government has shown itself to be able to employ blind people constructively. The State Department is still in the 19th century.”

FROM THE COLLECTION

Avraham Rabby's Braille Globe

Rabby Pushes Back and Testifies Publicly

Rabby went back and forth in phone calls and letters with officials at the Department of State. In his view, and that of other blind people and their advocates, the explanations for the rejection he received represented stereotypes and misconceptions about blind peoples’ abilities—or just defied logic.

In November 1988, Rabby went on television on ABC’s “Good Morning America” and debated the Director General of the Foreign Service, Ambassador George S. Vest. Vest argued that positions in the Foreign Service were “either incompatible with being blind or dangerous to the blind person himself.”

On February 1, 1989, Rabby testified in front of members of the U.S. House of Representatives’ Committee on the Post Office and Civil Service. Others offering testimony included two other blind applicants to the Foreign Service and the president of the National Federation of the Blind (NFB).

The tone was set by the presiding chairman, Congressman Gerry Sikorski of Minnesota, in his opening statement. He began by drawing attention to a history of concerns about the State Department’s treatment of applicants with disabilities. In 1987, an Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) report recommended the State Department take steps to accommodate blind persons.

“Now,” Congressmen Sikorski noted, “… we see that instead of opening doors to the Foreign Service, the Department of State installed a deadbolt lock,” referring to its recent decision—which Rabby encountered—to no longer allow blind exam takers to utilize readers. The State Department’s explanation was that security procedures prohibited reading classified materials out loud at overseas posts, unless within a special soundproofed room, so it made no sense to allow that accommodation during the exam process.

Congressman Tom Campbell of California followed Sikorski’s opening statement, offering his 18 years of experience as a volunteer reader for Recording for the Blind, including aiding blind people in academia and the practice of law in the federal government.

“When I first read of the State Department’s policy in the case of Avraham Rabby, I was shocked,” he said in his opening statement. “There appeared to be no consideration of the individual merits of Mr. Rabby, only the fact that he was blind.”

Rabby’s own testimony focused on what he outlined as the “five principal arguments” the State Department had given him for why blind people could not be employed in the Foreign Service. He laid out firm counterpoints for each:

- Blind people can’t meet the definition of full “worldwide availability” to serve? No one, blind or not, can just be “plucked” from one overseas and dropped into any another, without taking into consideration their skills, prior experiences, and family situation. Blindness is just one more characteristic to consider.

- The blind can’t independently work with classified material overseas? Classified information can be read using machine-assisted methods, or read out loud by a reader in already-existing special soundproofed spaces domestically and overseas. And Foreign Service officers don’t truly work independently – interpreters, diplomatic couriers, drivers, etc., assist Foreign Service Officers daily.

- A blind person couldn’t navigate daily life safely in dangerous overseas locations? Studies show blind people are statistically no more prone to injury or accident than sighted people. Rabby had also lived for 11 years in New York City, “… not the most kind and friendly and user-friendly city in the world.” In 1988, there were over 1,800 murders in the city.

- Blind people can’t adapt to unfamiliar settings and cultures? The United States Peace Corps, which sends its volunteers all over the world, much like the Foreign Service, “has hired and effectively used blind volunteers.”

- Diplomacy requires reading visual cues that blind people would miss? Most visual cues are not purely visual, but are accompanied by audible cues (e.g. shifting tone of voice) noticeable to a blind person who develops such skills.

Rabby’s overall point was simple: just let us serve according to our skills and abilities.

“[Blind people] do not seek kindness from the Foreign Service, and we do not believe that blind Foreign Service Officers should be treated any more or less gently than their sighted counterparts,” he said, adding, “… we know blind people can serve productively and do so on an absolutely equal footing with the sighted.”

– Avraham Rabby

The hearing included pointed questioning of two State Department officials who also attended. Congressmen Sikorski cited a 1982 complaint filed by Donald Galloway, a blind person who had served in the U.S. Peace Corps and had settled a discrimination case against the State Department in 1985 for $167,000.

The settlement agreement contained commitments from the State Department regarding affirmative action in the hiring, placement and advancement of “qualified handicapped individuals.”

Sikorski pushed the State Department officials to explain what had been done—concretely—in compliance with the 1985 settlement. The Department officials cited a 1986 investigation, leading to a 1987 report, which established a committee working towards changes in the medical clearance policies—those same policies which were cited in rejecting Rabby.

Sikorski wanted to know what was taking so long. Why, in 1989, was a very well-qualified candidate (Rami Rabby) who had passed the exams multiple times and received his security clearance not being hired?

“My point here is that I don’t think that’s [a] good-faith evaluation of the problem. And if we’re here to take the State Department’s statements that they want to move ahead and clear this up and make sure there aren’t any standards that act as barriers—I don’t have a lot of faith in those,” Sikorski said.

Around the same time as his appearance before Congress, Rabby filed a discrimination lawsuit against the State Department. He asked that the Department hire him and give him back pay for the years he was denied a job.

FROM THE COLLECTION

Guidebook for Blind Job Seekers

A Change in Policy Allows for Blind Officers

The breakthrough for Rabby and others came not long after, in late 1989. Just one day before a follow-up hearing scheduled by Congressman Sikorski, Rabby was called by the State Department and informed he was being accepted as an officer in the Foreign Service.

The State Department decided to allow the hiring of Rami Rabby and other blind officers on a case-by-case basis. He and other blind applicants had won their fight.

Multiple factors likely led to the decision, including the public scrutiny caused by the testimony of Rabby and others, and Rabby’s 1989 lawsuit. A new Director General of the Foreign Service, Edward J. Perkins, had also recently replaced George S. Vest—the man who had argued with Rabby on TV that the blind should not be allowed to join the Foreign Service.

At this time, Congress was also in the midst of passing legislation that would become the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990.

FROM THE COLLECTION

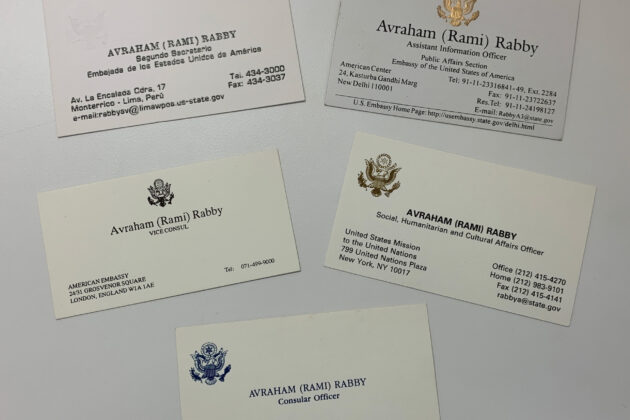

Avraham Rabby's Business Cards

Rabby was not the first blind person in the U.S. Foreign Service. That distinction belongs to Roy Glover in 1983, who passed the exams and was offered a position before an injury took his sight. Rabby’s successful advocacy helped establish the right of blind people to complete the Foreign Service exam process and to gain the medical clearance necessary to join.

He was joined in his Foreign Service orientation class by another blind person, Maryanne Masterson, who was already working at the State Department in another role but had wanted to join the Foreign Service. They are the first two blind people to successfully take the exams and become officers.

Rabby’s Success as a Diplomat and Advocate

Rami Rabby spent 17 years in the Foreign Service, serving abroad in the United Kingdom, Peru, and India. At assignments in the United States, he worked on Human Rights in Washington and at the United Nations in New York. He finished his career as the chief of the political section at the U.S. Embassy in Trinidad, having reached the mandatory retirement age of 65.

Rabby’s lifetime of advocacy began as a young adult, after a Y.M.C.A. in Chicago would not let him stay there. This experience motivated him to join the National Federation of the Blind (NFB), rising to become the first president of the Illinois Chapter. He later served as secretary of the national board.

Even while posted abroad during his diplomatic career, he continued to be active in the NFB. A family friend, Emi Giles, recalled in his New York Times obituary, “He had this crazy laugh. He would come to the annual Federation of the Blind convention in the U.S. every year (…) no matter where in the world he was posted.”

In an article in the NFB’s Braille Monitor after Rabby’s retirement, the editor commented on his victory, aided by the NFB. “[It] changed the lives and prospects of a handful of blind Americans who wish to work for the Department of State in other countries. More broadly, it removed a general barrier for all blind people.”

FROM THE COLLECTION

Avraham Rabby's White Cane

Sources consulted and for further reading:

A U.S. Diplomat With an Extraordinary Global View – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

Blind Man Wins Fight to Be Diplomat – Los Angeles Times (latimes.com)

Avraham Rabby, Blind Diplomat and Advocate, Is Dead at 77 – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

Avraham Rabby, blind activist who fought to enter Foreign Service, dies at 77 – The Washington Post

A U.S. Diplomat with an Extraordinary Global View (Braille Monitor, October 2007, nfb.org)

Related Teacher Resource

LESSON PLAN

Seeing the World Differently

This lesson plan explores Avraham Rabby’s advocacy for blind U.S. Foreign Service Officers, highlighting his efforts in promoting equal access for all, regardless of their disability.