After World War II, the United States entered into what was known as a “Cold War” with the Soviet Union, their allies, and other communist nations. This period included open conflict as well as global political, ideological, and economic rivalry.

To combat the influence and spread of communism around the world, the United States used diplomacy to promote democracy. To the United States and its allies, communism represented a threat to free trade, free elections, and individual freedoms. This threat was heightened by the increased number of nuclear weapons.

Berlin Airlift: Dawn of the Cold War in Europe

After World War II, Germany and its capital Berlin were divided in two. The western Allies (including the United States) occupied West Germany and West Berlin. The Soviet Union occupied East Germany and East Berlin. At this time, the United States and the Soviet Union were allies but were soon at odds when faced with the challenge of how to rebuild the political, economic, and infrastructure of war-torn Europe.

In June of 1948, the Soviets blocked the West’s access to West Berlin in an attempt to seize control of the entire city. President Harry S Truman’s administration responded with the Berlin Airlift: a massive campaign to drop food and supplies to West Berliners from the air.

Using Aid as a Tool of Diplomacy

By using aid as a diplomatic tool instead of a military attack, the United States kept the West Berliners supplied for nearly a year. Not wanting to risk a military confrontation, the Soviet Union backed down and opened the roads to the West in May of 1949.

Near the border with Soviet-controlled Poland, the city of Berlin was geographically vulnerable to communist influence. Citizens of West Berlin were surrounded and could not pass freely to East Berlin or through East Germany to travel to western democratic nations.

Thirteen years later, Berlin again became the center of Cold War tensions when, in a surprise move, the Soviets literally built the Berlin Wall overnight, dividing the city in half.

Diplomacy During the Civil Rights Movement

During the Cold War, U.S. diplomacy was focused on halting the spread of communism and limiting its influence where it already existed. American politicians believed that promoting democracy would expand individual liberties for people everywhere.

However, the democratic United States had a problem. It could not claim democracy as the best form of government when millions of its citizens experienced racial discrimination and segregation.

The Influence of American Diplomats

The modern Civil Rights movement required American diplomats to address this contradiction. They had to reconcile their advocacy for democracy abroad with the ongoing racial injustices at home.

Americans of color have represented the United States as diplomats since the 19th century. Specifically, their numbers significantly increased after WWII during the height of the Cold War and the dawn of the modern Civil Rights movement.

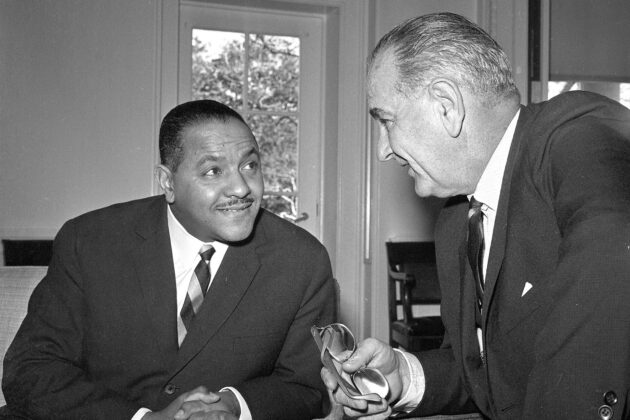

How did diplomats like Carl T. Rowan, Edward R. Dudley, Edith S. Sampson, and Sammy Lee represent American interests at home and abroad?

Saigon: the Tet Offensive and Evacuating an Embassy

This period is known as the Cold War because there was no direct military engagement between the United States and the Soviet Union.

However, this period was anything but “cold,” as multiple countries experienced internal violence as the U.S. and the Soviets supported competing factions fighting for power. These conflicts are known as proxy wars and also affected diplomats and the work of diplomacy overseas.

One such proxy war was the Vietnam War. By 1968, U.S. troops had been fighting in Vietnam for four years. China had been founded in 1949 as a communist state. Along with the Soviet Union, China provided aid to North Vietnamese communist forces fighting the U.S.-backed government in the south. That January, northern communist Viet Cong forces attacked a series of American targets during the Tet Offensive, including the U.S. embassy in Saigon. Tet is a Vietnamese holiday celebrating the New Year and came as a surprise attack on several military and diplomatic targets in South Vietnam.

The attack on the embassy shocked the American public, who had been led to believe that the United States was winning the war. A big part of successful diplomacy is accurately describing conditions overseas to Americans at home for their understanding and support. The Tet Offensive showed that the American people felt misled, and mass protests against the war increased. That March, President Johnson announced that he would not run for another term. Thousands more Americans and Vietnamese would die before the last U.S. combat troops left Vietnam in 1973.

American Diplomats Evacuate Thousands from Vietnam

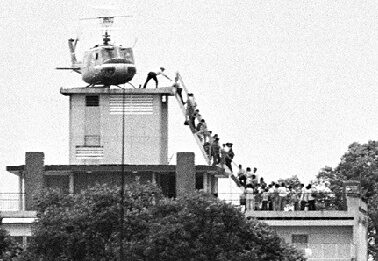

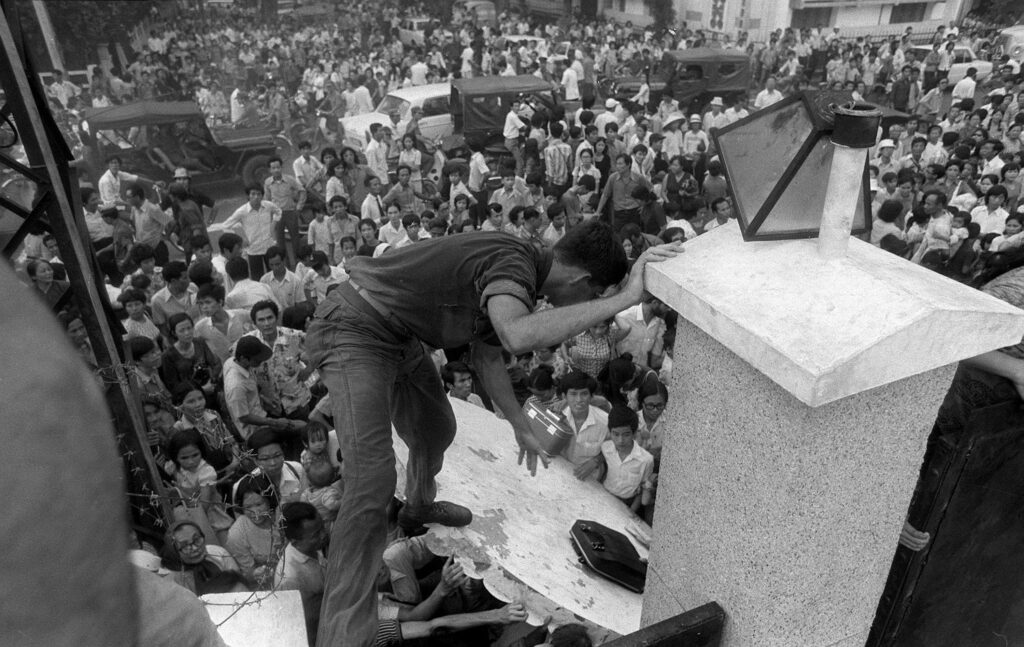

In April 1975, the U.S. embassy in Saigon was evacuated as communist forces took the city. The world watched closely as American diplomats evacuated thousands of American and Vietnamese citizens out of Saigon.

Some of these Vietnamese citizens worked for the U.S. government and, if left behind, were in extreme danger of communist retaliation. Consul General Cần Thơ, Francis Terry McNamara, refused to evacuate only the Americans from the consulate.

See how the evacuation of the Saigon embassy unfolded.

FROM THE COLLECTION

U.S. Consular Flag

Thawing Relations Through Ping Pong Diplomacy

As we have often seen in history, sometimes, the first people that are able to “break the ice” within “frozen” diplomatic relationships are ordinary citizens. We often refer to these people as “citizen diplomats.”

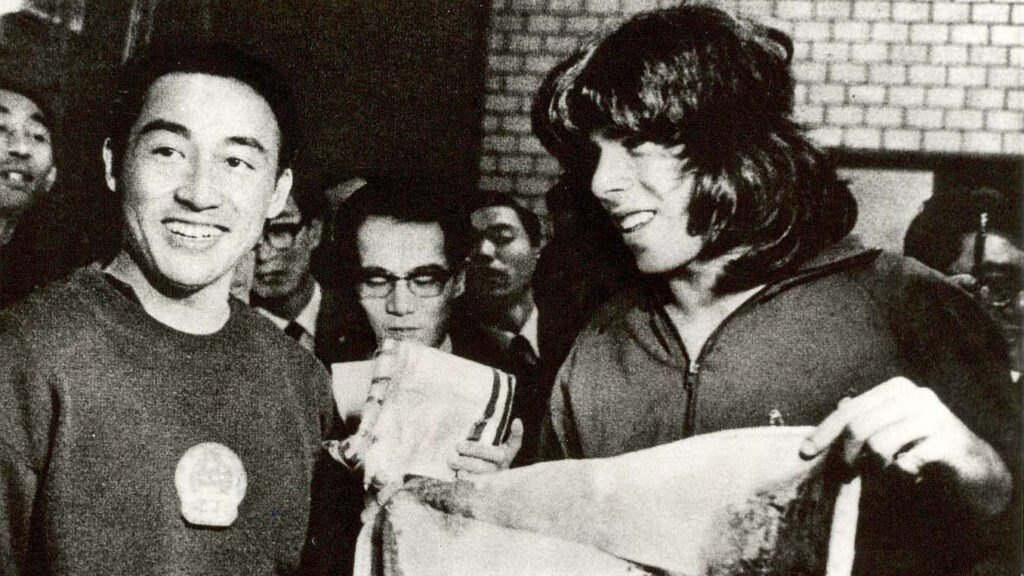

In April 1971, nine players from the U.S. Table Tennis team took a historic trip to China, becoming the first delegation of Americans to visit the country in decades. Following the 1949 Chinese Revolution, there had been no diplomatic ties, limited trade, and almost no contact between the United States and China.

Their trip started what became known as “ping-pong diplomacy” and helped lay the groundwork for establishing official diplomatic relations between the United States and China. Ping-pong diplomacy also improved people-to-people understanding and cultural exchange between the two nations.

Take a look at images, videos, and artifacts from this historic visit.

FROM THE COLLECTION

Ping Pong Paddle

The Fall of the Berlin Wall

The fall of the Berlin Wall and the reunification of Germany is often considered the symbolic end of the Cold War.

In the mid-1980s, through glasnost (openness and freedom ) and perestroika (economic restructuring), then-Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev demonstrated a willingness to loosen government strangleholds in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, including East Germany. While his openness was praised in the West, he met resistance from East German leader Erich Honecker and his regime.

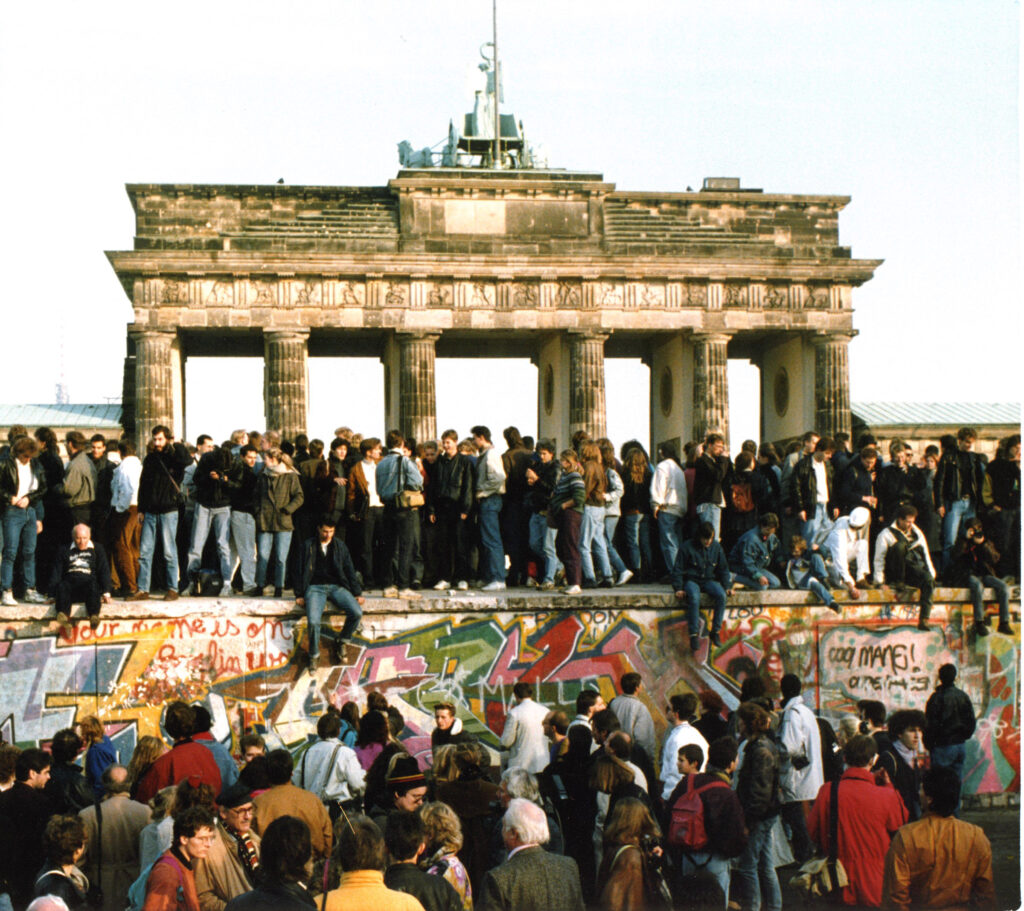

For decades, protests against suppression from members of the German Protestant church grew into a political movement. On Monday, November 4, 1989, evening services in Leipzig grew into a demonstration of over 100,000 protesters. The protestors demanded that Honecker resign. By November 9, protests in Leipzig had reached 500,000.

Two hours away in East Berlin, an estimated 1,000,000 citizens demonstrated in the streets. That evening of November 9, East Berlin police retreated, allowing protestors to cross into West Berlin peacefully. Many took sledgehammers to the wall, and the process of political reunification began.

The Diplomatic Agreement that Unified Germany

On October 3, 1990, the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany, known in diplomatic parlance as the “Two Plus Four Agreement,” was signed in Moscow. This treaty completed the reunification of Germany under international law.

The United States welcomed reunification. However, they understood the negotiations would be a complex diplomatic exercise in trust-building, working with existing alliances, and listening to the desires of the German people. American diplomatic leadership worked with all parties to ensure that reunification happened peacefully.

IN THE MUSEUM

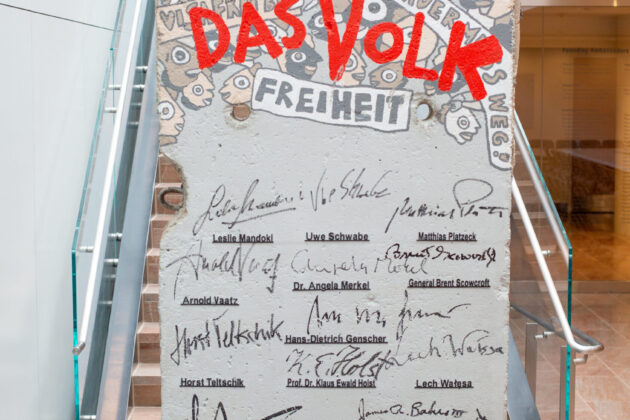

The "Signature Segment" of the Berlin Wall

Today, the National Museum of American Diplomacy in Washington, DC is home to the “Signature Segment” of the Berlin Wall. This 13-foot high, nearly three-ton piece of the wall has been signed by 27 leaders who played a significant role in advancing German reunification. They include U.S. President George H. W. Bush, U.S. Secretary of State James Baker, German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev, and Polish labor union leader and Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Lech Walesa, among others.

Story of Diplomacy

Carl T. Rowan: From Journalist to Diplomat

The path to becoming a diplomat is not always obvious. For Carl T. Rowan, he paved his path with his storytelling. His many articles on…

Collection Highlights

Ping-Pong Diplomacy: Artifacts from the Historic 1971 U.S. Table Tennis Trip to China

In April 1971, nine players from the U.S. Table Tennis team took a historic trip to China, becoming the first delegation of Americans to visit…

Story of Diplomacy

The Legacy of Edward R. Dudley: Civil Rights Activist and the First African American Ambassador

In 1949, Ambassador Edward R. Dudley was the first African American to hold the rank of ambassador. His legacy also includes a long history of…

Story of Diplomacy

The Fall of Saigon (1975): The Bravery of American Diplomats and Refugees

On April 30, 1975, the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese Army, effectively ending the Vietnam War. In the days before, U.S. forces evacuated thousands of Americans and South Vietnamese. American diplomats were on the frontlines, organizing what would be the most ambitious helicopter evacuation in history.

Story of Diplomacy

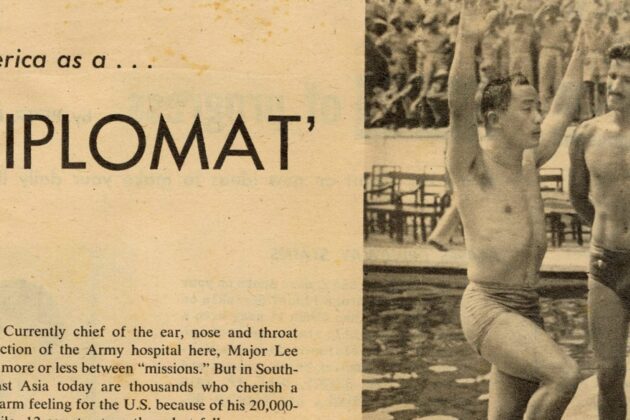

Dr. Sammy Lee: Olympic Champion and Goodwill Ambassador

Born in California in 1920 to Korean immigrant parents, Dr. Sammy Lee represented and served the United States in many ways. By the 1950s, Lee…